The Beirut municipality has granted the owner of the famous St. Georges Hotel, Fadi el Khoury, a license to rebuild and renovate the damaged landmark. After several years of dispute with Solidere, commemorated with a giant “Stop Solidere” sign hanging for all to see on the façade of the damaged hotel, El Khoury has been given the opportunity to give life back to the building.

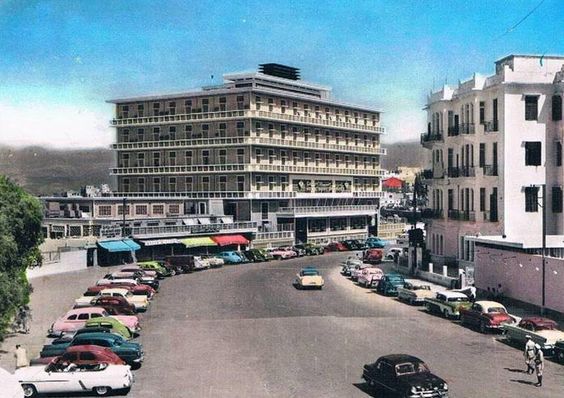

St. Georges Hotel is one of Beirut’s oldest remaining landmarks, initially conceived sometime during the 1920s and fully completed in 1934. Designed by local architect Antun Tabet in collaboration with three French colleagues, including pioneering architect Auguste Perret, the building’s aged exterior has stood the test of time, war, and bombings.

The Rise and Fall of St. Georges Hotel

The St. Georges Hotel was named after the legend of Saint Georges, the hero said to have slain a dragon terrorizing the shores of the bay. Its strategic location at the tip of the bay soon made the hotel incredibly popular amongst upper class visitors who frequented the hotel for its adjacent beach and boat club.

At the time of its conception, Lebanon was still under the rule of the French Mandate and so visitors of the hotel were almost exclusively French nationals. Very few Lebanese nationals were admitted, as told by the late Samir Kassir. Over time, Lebanese and Arab nationals began frequenting the hotel more often.

In the 1960s, the hotel’s popularity peaked. Lebanon, following its independence, had gained a reputation for being an ideal place of tourism and leisure. The hotel became the meeting point for oil executives, airline tycoons, and renowned bankers. Celebrities from around the world would soon help immortalize the hotel’s name: Marlon Brando, Elizabeth Taylor and Umm Kulthum are a few of the many names said to have visited the hotel.

Yet sectarian tensions were bubbling just underneath the surface. In 1975, the Lebanese civil war broke out, putting business to a stop. In the following years, the hotel became too expensive for many, and visits became scarce.

In 1983, militias began occupying the five-star resorts in the area, transforming them into bases where they could launch sniper attacks on each other. The St. Georges Hotel, the Holiday Inn and many others fell prey to the Battle of the Hotels.

Sometime during this period, the Syrian army would overtake the hotel until their withdrawal during the late ‘90s. The building had sustained significant damage, and was in deep need of renovation. But before any steps could be taken towards the improvement of the hotel, Lebanon’s former Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri set about reconstructing Beirut’s entire central and waterfront districts.

The Battle With Solidere

Under the name of newly-founded construction company Solidere in 1994, Rafiq al-Hariri was granted a myriad of rights for the purpose of rebuilding the city. El Khoury refused, sparking a long-term fight with Solidere that would torment the St. Georges Hotel for years to come.

Unfortunately for him, Hariri’s government backed Solidere, prompting the company to take full control of the bay and the area surrounding the hotel. Solidere blocked St. Georges’ access to the sea with a thick concrete wall.

In 2005, Hariri was ironically assassinated by a bombing that targeted his convoy just as it passed by the hotel. The building’s initial structure withheld the damage, leaving the building with a burnt façade it was set on reconstructing again. In commemoration of the assassination, a bronze statue of Rafiq al-Hariri has been instated right next to the hotel.

The St. Georges Hotel’s pool and restaurant have remained open to public use, yet the hotel itself has remained largely off-limits to the public. The beach has become a regular events venue, hosting parties and engagements amongst others. But the shadow of a corporate powerhouse still lurks above the hotel, a struggling survivor of an organization that refuses to stop until it has acquired the entire central district, filled it with high-rises and barred it from the public majority.

Solidere has failed to reconstruct Beirut’s central district. It has renovated buildings, built new roads, but it has shunned an entire section of the population from entering its streets. It has privatized once public land, barred off key historical monuments like the St. Georges Hotel, the Grand Theatre and the Egg for no clear purpose other than geographical and political domination.

Rafiq al-Hariri, once celebrated for rebuilding a city out of its very ashes, is far from a savior. When people like El Khoury have struggled and fought for years on end to seize some control over their properties, it begs the question of how long it will be before Solidere wants more, because it will find a way to get it. Unfortunately for us all, that has already been set in motion. Properties like Eden Bay continue to surface, and many are still fighting to take back what is rightfully theirs.

In 2019, Solidere’s contract with St. Georges ended. In 2020, El Khoury, after being coerced to give up the hotel and his plans for renovation, will finally be able to restore a building that has been haunted by its city’s violence and corruption for decades.

Read also: Reclaiming public space during the revolution: How we are reconnecting with Lebanese cities