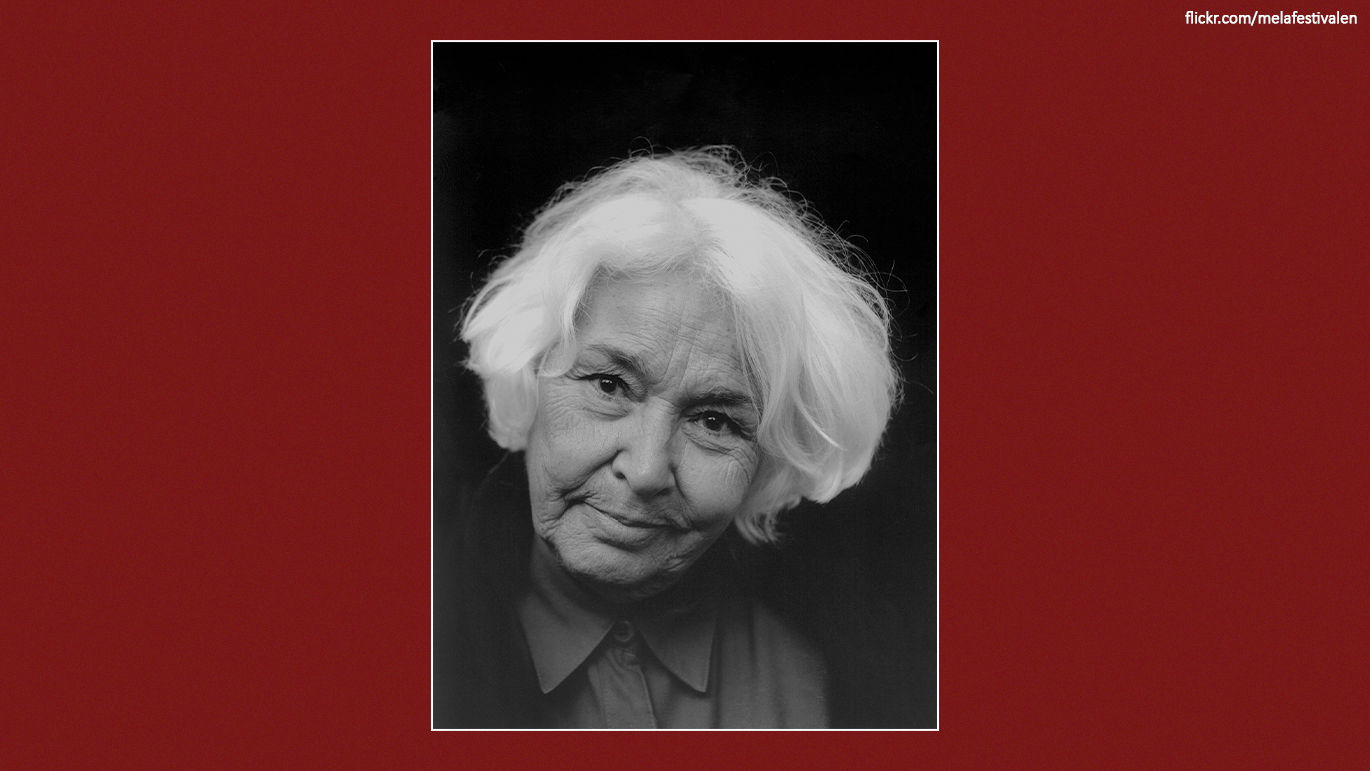

Egyptian writer, feminist thinker and psychiatrist Dr. Nawal El Saadawi died on Sunday at the age of 89, following a long battle against illness. She is survived by her son and daughter.

El Saadawi was born in October 1931 in a village north of Cairo. At the mere age of six, she underwent female circumcision that cut off her clitoris. She was raised in a relatively progressive household where her father encouraged self-respect and freedom of speech. When she was 10 years old, her family attempted to marry her off, but she and her mother firmly resisted.

She grew up to study medicine at Cairo University and later in New York’s Columbia University. During her years as a medical practitioner, Saadawi observed women’s physical and psychological problems, connecting them with oppressive cultural practices, patriarchal oppression, class oppression and imperialist oppression.

She became a fierce advocate against the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM), while also paving the way for the discussion on several issues pertaining to women’s rights.

“Since I was a child that deep wound left in my body has never healed,” she wrote in an autobiography while reflecting on her experience with FGM.

In 1972, she published her celebrated book “Women and Sex,” in which she confronts and contextualizes the various aggressions perpetrated by men and the patriarchy against women’s bodies. The book became a massive part of the second-wave feminism movement.

Saadawi lost her job at the Egyptian health ministry as a result, including various other positions such as chief editor of a health journal. In 1981, she published a feminist magazine called “Confrontation,” leading to her famous imprisonment by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Yet Saadawi’s determination led her to resume her endeavours from behind prison bars.

While in prison, she formed the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association as the first legal and independent feminist group in Egypt. She continued to write, using a black eyebrow pencil smuggled in by a fellow prisoner and a roll of old toilet paper to record her thoughts.

Her writings were later on published in 1983 as “Memoirs from the Women’s Prison.”

“When I got out, my life was in constant danger from religious fundamentalists. What I could say and do in Egypt was restricted from then until now. I had to go abroad to teach,” she said during a talk at the CUNY Graduate Center on March 16. 2011.

In 1988, after various threats, she fled Egypt and accepted an offer to teach at Duke University. She resumed her activist efforts and continued advocating for women’s rights from afar. She was often criticized for being a supporter of dictatorships in Egypt.

“I belong to the ‘historical socialist-feminists,’ women who were inspired by our mothers and grandmothers, and by the goddess Isis,” she said. “We are against all forms of male domination, including the traditional family and including imperialism.”

In 2005, she attempted to run in the Egyptian presidential election, before stepping down as a result of restrictive requirements for first-time candidates. She also accused security forces of not allowing her to hold rallies.

In 2011, she took part in the Tahrir Square protests against Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship of Egypt.

She has won a total of nine awards and honors, including being named one of Time Magazine’s 100 Women of the Year in 2020. At the time of her passing, she has authored 50 books.

Saadawi’s work is a reflection of feminist thought in the Arab world over the past few years. Despite the controversies surrounding her political stances, she is celebrated for engaging people in thought-provoking work that proved itself essential at its time of publication. Saadawi put forth feminist concepts, and paved a way for discussions surrounding oppression, classism, feminism within the context of colonialism, and female genital mutilation.