In a free market economy, like that of Lebanon, the model is repeatedly questioned because of the difficulty of dissociating the political status of the country from its economic dysfunction, especially with regards to its fiscal policy “plans”.

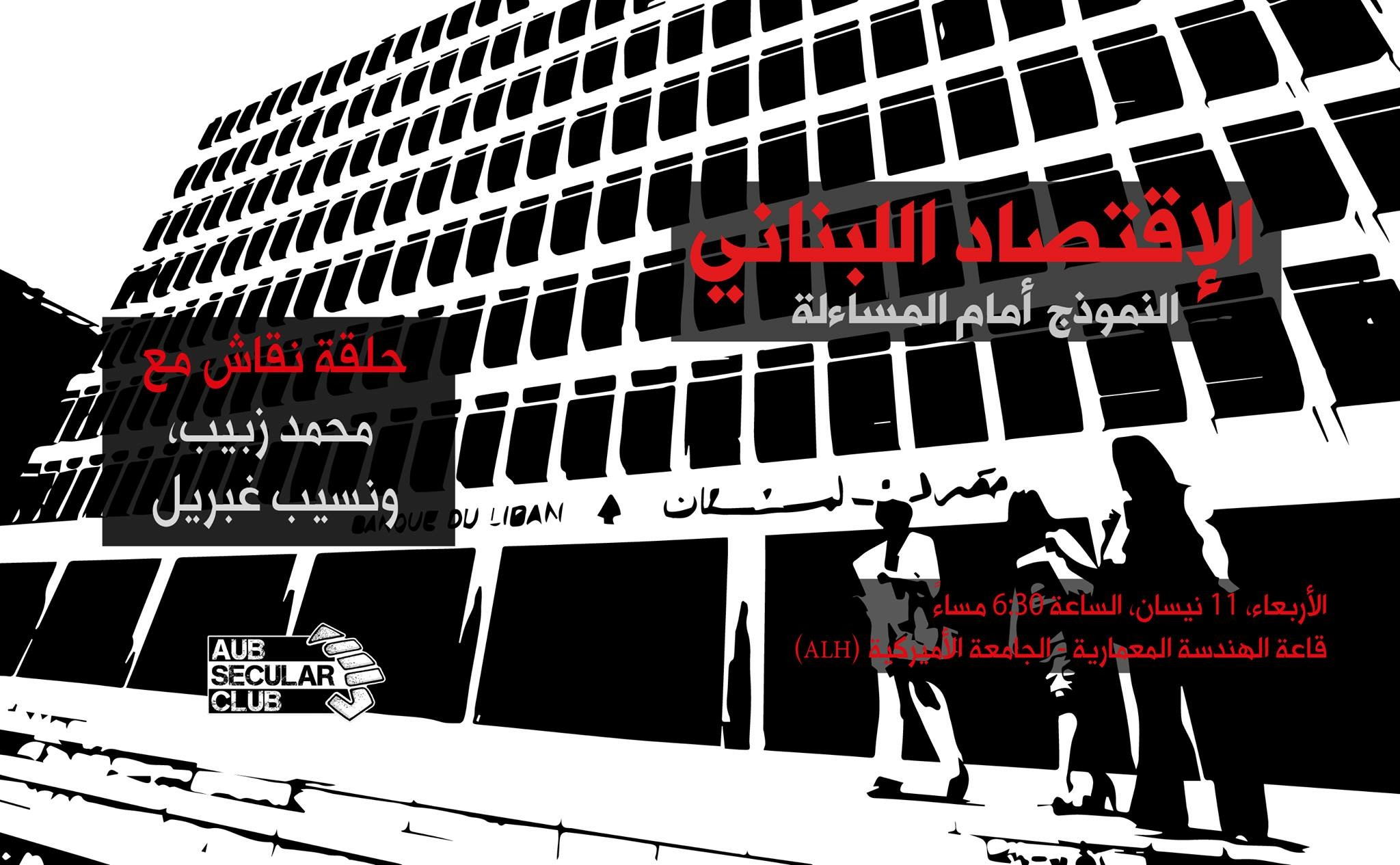

The AUB Secular Club hosted an event on April 11 to discuss the Lebanese economy and the Central Bank’s policies and whether or not the two interact with the current political system, frequently called an “accommodating regime.”

Mohamad Zbeeb, the Editor of the Economy And Society Section at Al-Akhbar newspaper, and Nassib Ghobril, head of economic research at Byblos Bank, approach the topic from different points of view. The conflict of ideas commences with the description of the economy on one hand, and the proposed alternatives and cost-benefit frameworks on another.

Ghobril begins with a thorough analysis of the state’s dysfunction and its inability to create a coherent plan to bring about investment in various sectors. He complements this point by suggesting that the consumer’s trust in the state is tied to political developments, which consistently deteriorates in Lebanon. Ghobril, starting with the said evaluation of the state, suggests this doesn’t apply to the Central Bank and the banking sector as a whole, which has supposedly facilitated investment and loans and prevented various financial crises.

Zbeeb observes the crisis from a completely different lens, suggesting the very structure of the Lebanese economy, since its inception, does not allow for coherent planning or a well-defined approach for the state’s role, which, according to Zbeeb, is a central component of the debate in many countries.

He claims that the most comprehensive conclusions arrived at in countries such as those in Western Europe is that the state’s role is crucial in preventing such economic crises. Adding to that, Zbeeb believes replacing the state with the Central Bank in that system and basing an economy off the banking sector is not a start for a genuinely productive economy (comprising sectors like agriculture and the manufacturing industry). Banks have made steep profits off of interest, as the state’s deficit is mainly financed by local banks.

Zbeeb also highlighted that a discussion on incentives is futile without taking into consideration that the incentive for profit may come at the expense of genuine productivity. One example brought up is the extraordinary amount of deposits put in banks in exchange for interest revenues.

Another strategy frequently established in Lebanon is buying land without productive use and accumulating a profit off of it as the prices rise. This very process does not encourage investors to start small businesses and factories, as depositing their earnings entails a lower risk on investment. On the other hand, Zbeeb suggests we redefine the way incentives are looked at and that such a strategy isn’t foreign to the rest of the world, especially the economies of West Europe.

The panelists also agreed on several points. They both acknowledges that there are costs for many initiatives implemented by the Central Bank, and that the banking sector shouldn’t be the only active pillar in the Lebanese economy.

Nevertheless, Ghobril believes that the Central Bank was left without a choice with regards to many of its policies, most notably the financial engineering strategy of 2016, while Zbeeb believes its negative implications outweighed any positive consequences related to stabilizing the Lira. The latter then mentions that some of the country’s big banks have made a hefty profit because of such policies,

The discussion revealed a general consensus on the state’s dysfunction and the persistent issue of a regime struggling since the Civil War. The debate, which has accelerated since 2015, also relates to the alternatives presented by different independent campaigns in the upcoming elections, especially on issues of privatization, differing tax policies and various critiques of the financial crisis.