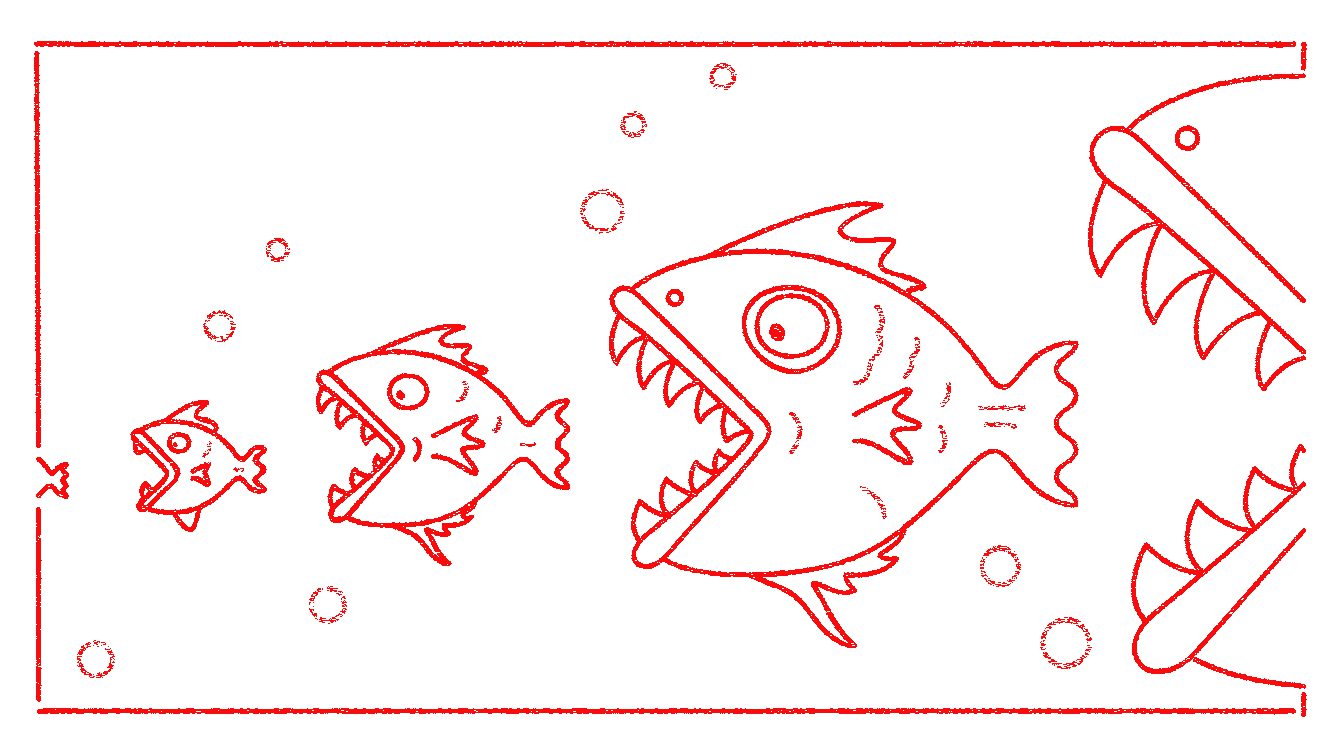

By approving the Competition Law in its last session, Parliament may have weakened exclusive dealers and shook the foundations that Lebanon’s monopolists built their empires on but it did not deal them a killing blow. The law, which spent 14 years on the table before being approved, leaves them with room to breathe and thrive through one of its articles.

Exclusive dealers have monopolized more than 60 percent of goods consumed locally, often supported by or partnered with politicians and other influential public figures.

Lebanese people have suffered under the whims and mercies of these importers and dealers for years, and today more than ever. There are days when fuel, wheat, medicine, and children’s milk are absent from the market, hidden away by importers in the hopes of exerting political influence and making a greater profit down the line.

In 1967, traders with exclusive agencies in Lebanon were granted unparalleled protection by a judicial decree and customs officials. They were given the right to object to the import of goods by other traders, with authorities militarized for tens of years to protect and serve their interests.

Dealers have, over the years, succeeded in foiling any attempt to break or shake their monopolies—up until the Competition Law was passed by Parliament on February 22, 2022. But has Lebanon truly succeeded in breaking the exploitative cycle of exclusivity, or has it given monopolists a leeway to proceed with exerting their influence over the market?

Lebanon’s monopolies and dangerous practices

Lebanon’s Competition Law has made it the latest country in the world to end exclusive distributorships. However, more than 3,316 exclusive agencies currently operate in Lebanon—of which 316 are legally registered with the Ministry of Economy.

The rest still exercise authority as if they are legally registered, obtaining court rulings in their favor to prevent the entry of any competing goods into the market.

The current state of Lebanon’s exclusive agencies complicates the mechanism of applying the newly-passed competition law and breaking the practices of both declared and unauthorized exclusive dealers.

Their dangerous methods of operation in times of crisis makes the application of the law life-saving. How can we forget the way these exclusive agencies dried the local markets of children’s milk a few months ago to force the Central Bank to cover their import costs with subsidized dollars? Neither the state nor other traders could import infant formula at the time by virtue of a law protecting the exclusive agent, all at the expense of children’s health and lives.

With that in mind, the new law can be considered an accomplishment because it limits the reach of these monopolists. But it’s far from being a perfect law.

Not only do exclusive distributorships control more than 60 percent of the Lebanese market, they earn billions of dollars in profit from it at the expense of everyday people. Only one or two companies have monopolized the following local markets: household gas, soil, gravel, soft drinks, sparkling water, telecommunications, iron, infant formula, and others.

Despite the presence of 14 importing companies in the fuel sector, they’ve still managed to collectively abuse their control over the market. Likewise, 15 dealerships monopolize the new automobile sector, 4 monopolize most of the pharmaceutical sector, and 13 control wheat and flour.

Most of the companies and alliances monopolizing the Lebanese market are either protected or owned by politicians.

Article 9: A point of contention

The Competition Law was met with criticism and objections from jurists and those interested in public affairs. Perhaps the fiercest objections came from the Consumer Protection Association, whose president intends to appeal the law before the Constitutional Council due to Article 9.

Despite the importance of implementing the competition law to break the monopolization of the economic sectors in Lebanon for the past several years, a loophole in Article 9 allows exclusive dealers to proceed with the same business approach that prevails today.

The article acknowledges and legitimizes market dominance of up to 35 percent, an incredibly high figure that prompted Zuhair Berro—president of the Consumer Protection Association— to describe the newly-approved legislature as the “law of consecrating monopolies.”

Berro believes that the law, in its current form, will not induce change related to the monopolization of the market. The way exclusive dealerships are mapped in Lebanon will mostly remain the same.

“In the best circumstances, some companies with shares that exceed 35 percent of the market will be forced to reorganize themselves and establish new companies under fake names to remain dominant over the market,” he told Beirut Today.

Berro added that the market dominance percentage should not exceed 15 percent, considering the market to be monopolized and not free if it is dominated by only three companies.

He believes a 35 percent market share will not break monopolies up, aided in his thinking by the example of the local cement industry. Today, three companies run the cement industry in Lebanon and are selling a ton at a whopping $100—while its price in neighboring countries ranges between $20 and $25.

Judith El-Tini, a legal expert on the Competition Law, agrees with the Consumer Protection Association on the principle that 35 percent is too high.

In conversation with Beirut Today, she found that this percentage could have been set at, for example, about 20 percent. She also pointed out that the French trade law does not specify a market dominance percentage because it does not allow markets to be dominated by monopolies in the first place.

Berro stressed that no free market is exempt from real competition. “The law manages monopolies instead of ensuring competition,” he said.

On whose authority?

Article 9 of the Competition Law prohibits anyone with a dominant position in the market, whether a person, company, group of people or a group of companies, from abusing their status in a way that limits fair competition in the relevant sector.

The article enumerates, by way of example but not limited to, acts that violate, limit or prevent competition. It also considers the entity to be a dominant position in the market if their share is greater than 35 percent. But why not adopt a lower percentage, such as 20 percent? What are the foundations upon which this figure was built?

Article 9 also considers a group of people or companies to be in a dominant position in a particular market if the group consists of three or less entities making up 45 percent of the market, or if they consist of five or less entities making up 55 percent of the market.

Why, for example, was it not forbidden for a group consisting of five entities at most to take possession of a third of the market? The answer is that the law wanted to weaken monopolies, but not break them.

If the legislative authorities took inspiration for Lebanese laws from French laws, then why hasn’t it taken inspiration from the French trade law?