This article was originally published on Beirut Today’s Arabic site.

Lebanese officials persistently and repeatedly stumble when it comes to protecting Lebanon and its people from the deadly novel virus, a show of their preference for private gains over public wellbeing. The failures and inaction of Lebanese authorities when it comes to managing the COVID-19 pandemic are not an exception, but rather the “fundamental criteria of the government and its public institutions.”

At the basis of the terrible and terrifying surge of COVID-19 cases in Lebanon lies hesitation, confusion, and disagreements between the health, security and political authorities. Adopted policies resulted in further tragedy for everyday citizens, who are living a bleak reality and expecting a similar future in light of the nation’s multiple crises.

“I’d rather die of corona than die of hunger” has become an everyday statement, with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia estimating that over 50 percent of the population in Lebanon now lives under the poverty line. Citizens have been forced to circumvent laws and rebel against the lockdown while going down the “crooked path” that authorities carved out.

Hopes in the ability of the fourth total lockdown to contain the pandemic –which authorities have been trying to do since last February– are low given the overwhelmed healthcare sector and hospitals filled to the brim of collapse.

Between the inaction of authorities and the laxity of citizens, daily casualties have risen dramatically and intensive care units are flooded with COVID-19 patients. But who will secure the necessary funds for Lebanon’s poorest and most vulnerable during the total lockdown? And are there actual guarantees that protect the rights of citizens?

Rami Fawaz, Lebanon’s director of the International Human Rights Commission, points to the possibility of increasing inequality and discrimination among citizens as we approach something worse than the “Italian scenario.”

“The state has a national plan that was launched on October 17, 2011 to help the poorest families through the Ministry of Social Affairs,” Fawaz explained to Beirut Today. “This project is partially funded by the World Bank and its services are funded by the Lebanese government, such that the team works through the Development Services Centers affiliated with the Ministry of Social Affairs.”

However, the project was poorly implemented.

“Despite the contribution of this project to granting some citizens cards to cover the difference in the health bill by the Ministry of Public Health, it was not activated and given priority –especially after the explosion of August 4,” he said.

The health sector hits the stage of “clinical death”

It seems that Lebanon has no hope for overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic as long as citizens do not adhere to the preventive measures and the relevant authorities do not impose serious and meaningful safety measures.

Lebanon’s test positivity rate exceeded 15 percent in recent weeks, pushing hospitals and clinics to their limit. On Tuesday, Lebanon recorded 3,5050 new coronavirus cases and a new record high daily toll of 73 cases.

In total, the tiny country of 6.8 million citizens, residents and refugees has seen 285,754 cases since February 2020 and 2,477 deaths.

“Government hospitals have become fully equipped after decades of neglect, compared to the private medical facilities that are in critical condition today, from hospitals, clinics, and laboratories to medicines and medical and nursing staff,” said Fawaz.

See also | Hospitals and hunger: Lebanon’s COVID-19 battle is multipronged

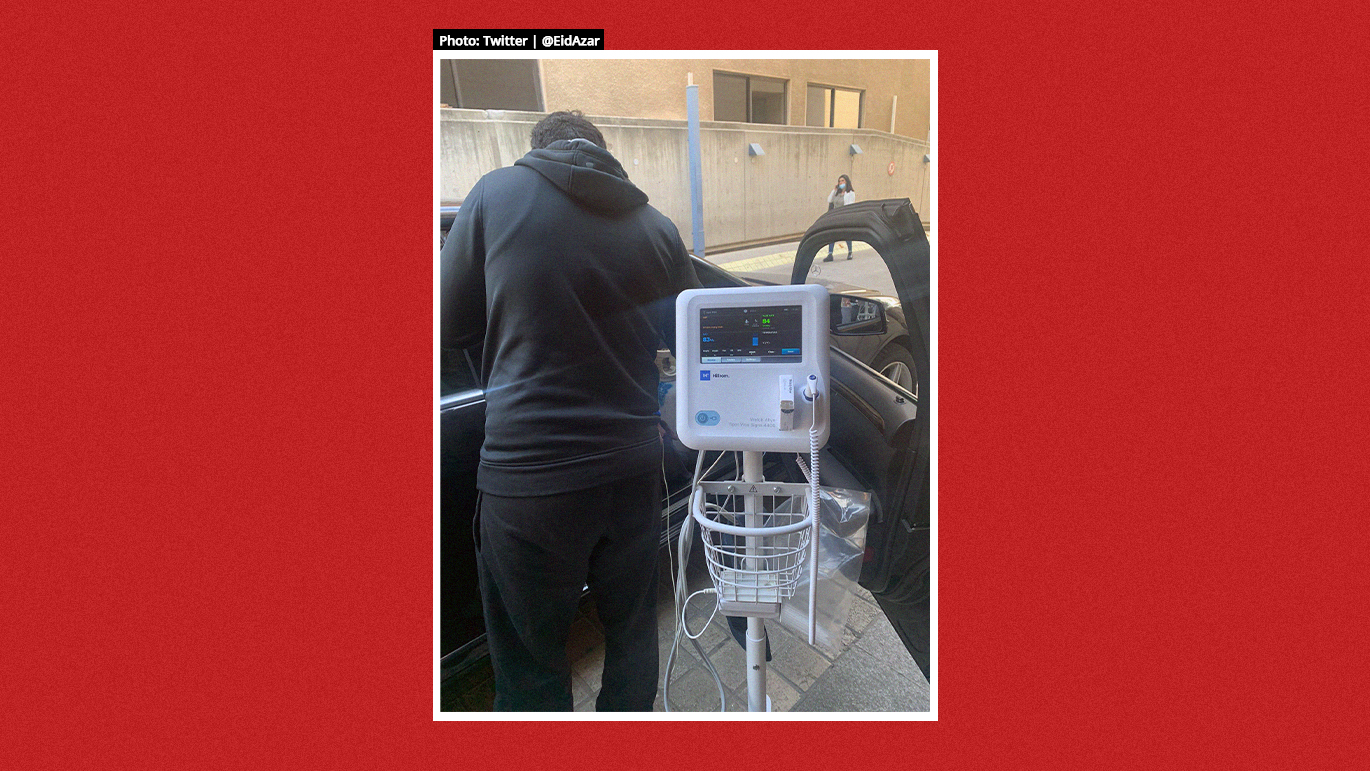

His statement can be felt on the ground in dangerous ways: COVID-19 beds have run out, emergency rooms are full, patients are waiting for room vacancies in parking lots or hospital entrances, and some are travelling far from their areas of residence to receive medical attention despite the gravity of their conditions.

Already suffering from an acute shortage of medical staff as a result of Lebanon’s ongoing “brain drain,” Lebanon’s medical workers have fallen victim to COVID-19 infections –with positivity rates among their ranks also hitting around 20 percent.

Meanwhile, every two patients in intensive care wards need the care of three or four nurses. Their dwindling numbers and infection rates have led to extreme physical and psychological pressure felt by Lebanon’s medical workers. In some cases, their shifts stretch over 24 continuous hours –while their salaries do not exceed a million Lebanese liras.

The economic crisis has rendered private hospitals unable to open additional departments up for COVID-19 patients, with the main reason being the state’s failure to pay millions of dollars in accumulated dues to them.

The cost of equipping new intensive care units with respirators and other necessary equipment approximately amounts to $40,000. A bed in a regular room costs no less than $15,000.

Currently, 90 out of 127 private hospitals in Lebanon provide 300 intensive care beds for critical cases and 500 regular beds.

To make matters worse, essential medicines have disappeared from Lebanese pharmacies –with traders and medicinal companies seeking commercial profit.

“Pharmaceutical companies are inhumanely gambling with citizens’ health. They are not subject to accountability, prosecution or legal oversight, bearing in mind that medicines receive support from the state and have bank procedures that leaves them unaffected by the exchange rate,” said Fawaz.

Whenever the medical community puts its hopes in a specific drug to treat COVID-19 patients, it rapidly vanishes from pharmacies as a result of panic-buying –only to be listed a few days later at expensive black market prices that hospitals are unable to pay for in hard currency.

Respirators, for example, have become a rare commodity in Lebanon. Those with money can breathe, and those without it die.