Anger once again predominates Lebanon’s political and social atmosphere following the events which have posed grave dangers to the livelihood of its residents, most recently revolving around the burning of the Beirut port during the second week of September.

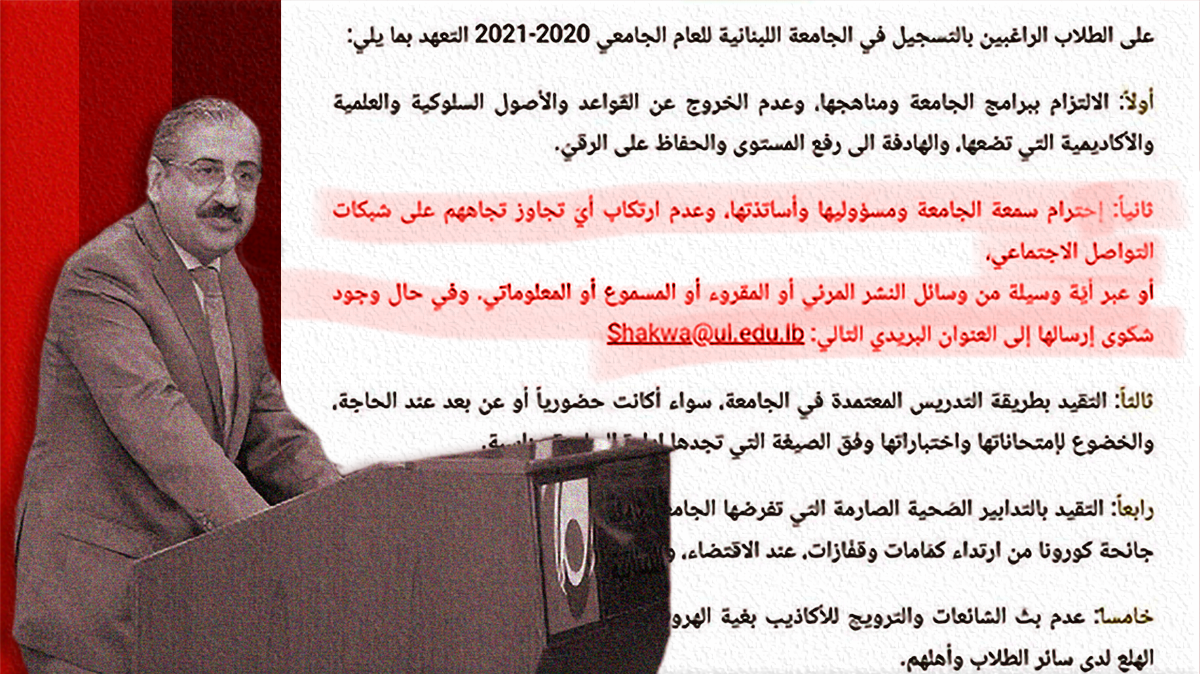

When articulated, such rebellious frustrations have been met with either live and rubber bullets, detention, or incitement from top-ranking government officials. Lebanese University President Fouad Ayoub had a different approach: forcing students to pledge allegiance.

Lebanon’s only public university has faced a wide range of issues in the past few months, most notably the dilemma of students being obliged to sit for written exams in locations in which little-to-no health precautions were adequately implemented.

After a strongly worded online campaign titled “the Exams of Death,” tensions surfaced between the student body and the administration, with the latter increasingly losing its patience when dealing with opposition.

“The person mobilizing against the Lebanese University is an ex-professor accused of plundering public money,” announced Ayoub in response to growing student discontent in early August.

As scapegoats aren’t the only tools utilized by authoritarian personalities, Ayoub went further to issue a circular insinuating that students ought to sign a pledge not to “insult” the Lebanese University or “damage its reputation” on social media or other platforms. Ayoub seemingly expected obedience, but the student body had different arrangements.

Circular Nº34: A microcosm of Lebanese politics

The circular, now known as “circular 34,” was released on September 7 and specifically addressed students enrolling in university for the year 2020–2021. Accordingly, it constituted a list of points, taking the form of “guiding principles.”

The second point in the circular demands that students refrain from “insulting administrators and professors” on social media platforms. Instead, a “complaints email” was displayed so that students can refer their issues in a private setting.

Meanwhile, the fifth point demands that students “not spread lies and rumors” about the university’s overwhelmingly deteriorating performance.

As it further asks all incoming students to sign a pledge that all the aforementioned points will be pursued, students fear they may face disciplinary measures in response to hard-hitting criticism.

“It’s first important to highlight that the Lebanese University is a microcosm of Lebanese politics, with regional divisions sorted according to sect-based accommodations,” said LU student and activist Leen Habhab. “In this context, tens of thousands of students enrolling in the Lebanese University on an annual basis will get used to a Ba’athist-like environment hostile to criticism and free speech.”

“The prevalence of such a culture in a public institution will only reinforce the increasingly repressive socio-political reality of the country for generations to come.”

For students like Leen, off-campus politics and on-campus developments are inseparable. As such, the university transforms into a space in which the ruling hegemony reinforces its cultural norms within campus walls.

“While Syrian regime troops were kicked out of Lebanon in 2005, the politics of repression remains a powerful tool utilized by our politicians in a wide range of contexts,” she continued.

With students increasingly anxious about their future prospects amid dangerous socio-economic developments, such a circular renders critical discussion the least of their priorities in the short-term.

For young activists, the notice poses great limits to LU students hoping to open up a constructive conversation about their role as participants in the political process.

Students fight back: LU administration taken to court

After the circular was issued, plenty of student and youth groups immediately responded with contempt for the administration and its president by refuting its essence on social media and national television.

“..This is merely a reflection of the ways in which we are treated by the state as citizens,” said a statement issued by the Coalition of Lebanese University Students.

The statement, which spread on several class WhatsApp groups to garner student signatures, refuted the rationale behind such a pledge and instead called on the administration to “invest in the interests of students.”

More severe posts targeted Ayoub’s increasingly authoritarian character, suggesting that these policies have contributed to militarizing the LU campus and fostering a repressive atmosphere in the country.

In parallel, a lawsuit was issued by Tayseer Zaatari to the interim relief judge. Zaatari, an LU student and member of the Coalition of Lebanese University Students, believed that the illegality of such a step ought to have been highlighted to the Lebanese public.

“While we are still waiting for an official decision from the interim relief judge, given that such responses require a five day or one week window, it is unambiguously clear that such a pledge goes against the law, noting that it requires that a person commit a certain violation prior to signing the pledge,” Zaatari told Beirut Today.

Following these developments on the level of the student body, Ayoub released a “clarification” circulated to all deans across the university to inform them that students are no longer obliged to sign any papers in regards to this issue.

The clarification further mentioned that the very “purpose” of circular 34 has been already achieved, taking note of the fact that most students have now at least read it following the controversy which had arisen in the past few days.

“Eventually, Ayoub kept the circular but retracted the pledge, conceding that students do not have to sign anything given that they have all been informed of the pledge,” said Zaatari.

Zaatari notes that the circular is simply a reiteration of the university’s bylaws, and hence represents no added value to the information students already know.

Although Ayoub rhetorically withdrew from letting administrative units compel students to sign such a pledge, other means were used to make sure the vast majority of incoming new students comply out of fear and ignorance.

“As mentioned previously, the circular no longer applies, however not officially –this verbal withdrawal was only circulated amongst faculty managers and deans,” writes LU alumnus and activist Samir Skayni.

“..Illegitimate and unelected student councils are trying their best to make sure students sign this pledge, […] Fouad Ayoub retracted [the pledge], but the student-based mafias in control of our councils have yet to do so,” he continued.

Since the mid-1990s, the Lebanese University’s student unions have been increasingly co-opted by powerful sectarian ruling parties. Accordingly, little-to-no rights-based initiatives concerning the very interests of students as an independent social group were allowed to foster on campus.

While autonomous on-campus formations grew stronger after October 17, recurrent cancellation and postponement of university elections have paralyzed any chance to influence decision-making and bargain for student rights.

Moreover, coupled with repetitive attempts to silence opposition, the very process of mobilizing students towards a transformative political end is threatened by an economic crisis and waves of emigration amongst the youth.

Despite these challenges, the latest conversation demonstrates a more powerful protest narrative whose persistent and rebellious protagonists have little to lose at such a stage of contention.