For the past few weeks, my Twitter feed has been full of conversations on white privilege. Triggered by the unlawful killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers in the United States, American activists took to the streets and social media to voice their outrage at the country’s systemic racism. The world soon followed as activists from various continents took to the streets in support.

Across the world, activists echoed the same sentiments: African Americans had long given their lives to a system that favours White people, and change was long overdue. In the Arab World, sentiments are divided: Some advocate against abolishing racist practices in the region, but others actively promote and participate in them.

Anti-black sentiments are a long-standing face of Arab societies, which have a significant history of being colonised and influenced by Western rule. A popular misconception today is that people of colour cannot express racism to other ethnic minorities, but as time will tell again and again, racism is alive and well in the Arab world.

Colonialism and the arrival of blackface

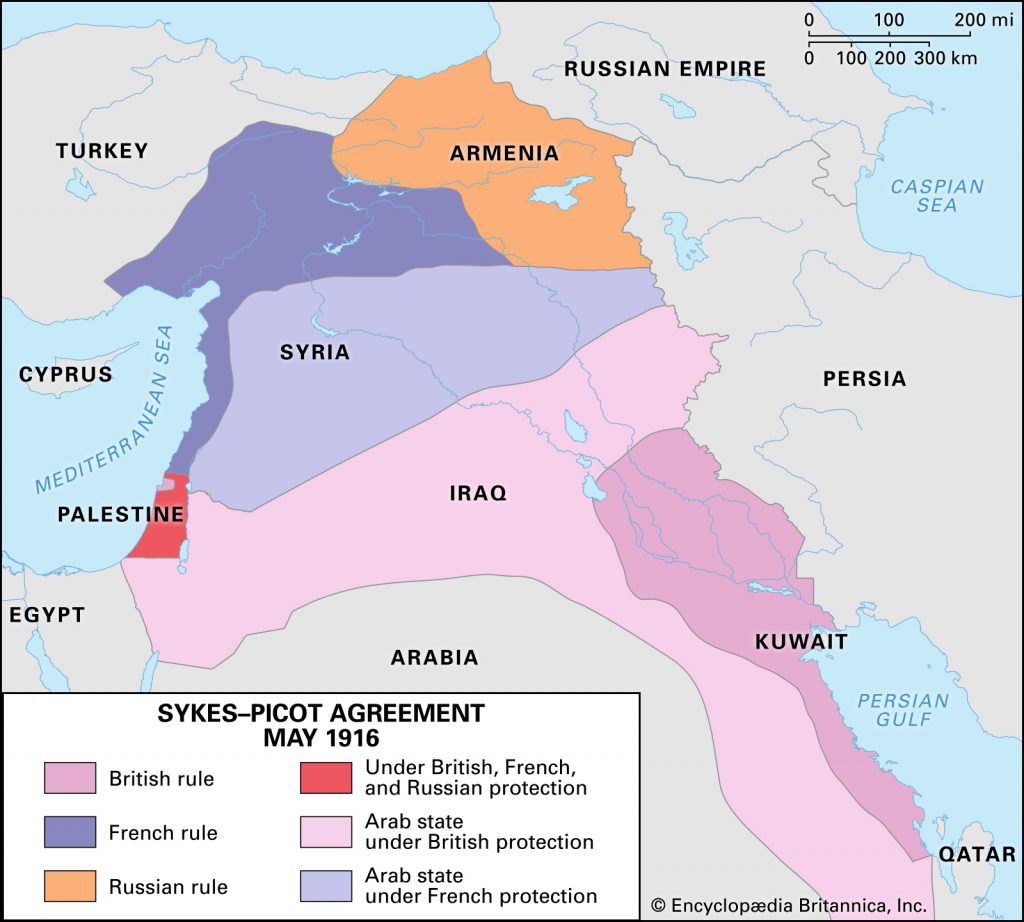

To understand the region’s anti-black sentiments, it is essential to reflect on its history of colonialism and imperialism. Following the first World War, France and the United Kingdom engaged in an agreement that would effectively divide the Arab World into colonies at their leisure.

After the end of World War I, the downfall of the Ottoman Empire meant its occupied lands in the MENA region were free for winning allies to take advantage of. The Sykes-Picot agreement was created as a basis for division of land between France and the United Kingdom, and it effectively changed the face of the Arab World.

The division meant that European countries had the upper hand in the region, and began to exert soft power by dismantling Arab culture in promotion of their own. Under colonial rule, entire political, economic and educational systems were changed. The Arab language was tossed aside in favour of Western languages, and local history was deemed unimportant when compared to Western history. Rather than establishing themselves as independent countries outside of Ottoman rule, the Arab World became a conglomerate of colonies.

The arrival of blackface in the region is closely linked to the arrival of Western colonialism. Blackface, a racist practice in which individuals of fairer skin tones wear dark black makeup in imitation of black individuals, is in essence an American creation that was later diffused globally.

Blackface emerged in the United States during the late nineteenth century, when white actors wore dark black makeup to imitate African workers in the country’s Southern plantations. This was done as a form of cruel satire that mostly depicted African Americans as rapists and harassers.

Exactly how blackface arrived to the Arab region is unclear, but it is assumed to have been a direct effect of British colonial rule in Egypt. Today, blackface is alive and well in Arab entertainment as its comedians and performers wear it in hopes of inciting laughter amongst audiences.

Comedy shows in Egypt, Kuwait and Libya have regularly portrayed blackface, as has Lebanese pop star Myriam Fares in one of her music videos. MBC, the region’s largest satellite network, has gone on to air shows with these racist skits despite criticism from local and international communities.

The performers were the recipients of severe backlash from Arabs who advocate against the practice, to little or no avail. After coming under fire for donning blackface in a show for MBC, Egyptian comedian Shaimaa Seif refuted comments against her performance citing that “it’s just comedy.”

Following the outburst of Black Lives Matter protests across the USA, Lebanese singer Tania Saleh posted a photoshopped picture of her face onto a black woman’s head in a miscalculated move of solidarity. In a failed attempt to express support, Saleh wrote “I wish I was black, today more than ever,” essentially turning a deaf ear to the struggles of black people in favour of fetishizing their beauty.

كل عمري كنت احلم كون سوداء

I wish I was black, today more than ever… Sending my love and full support to the people who demand equality and justice for all races anywhere in the world.#nojusticenopeace #GeorgeFloyd #blacklivesmatter #policestate #whitesupremacy pic.twitter.com/KAWxU8tjVq— Tania Saleh (@TaniaSaleh) June 1, 2020

Following backlash from local activists, Saleh refused to apologize for her actions and has yet to take her post down. Lebanese performer Lama el Amine took to Instagram to address Saleh’s comments in a video, listing instances where she herself encountered racism as a black woman in the country.

In spite of these comments, other individuals have followed in Saleh’s footsteps, photoshopping black skin tone onto their bodies or donning black makeup.

Arabs identifying as white

The issue not only lies in blackface, because racism itself is not only expressed explicitly. In an essay titled “Wearing Where You’re At: Immigration and UK Fashion,” British Egyptian writer Sabrina Mahfouz wrote that “many people from North Africa and the Middle East regard themselves as white, whilst stating that there are also black people of that nationality.”

“In Egypt, for example, those who have a darker skin tone and more of a sub-Saharan African physiognomy may be called “Black Egyptians” by other Egyptians who, if pressed, would self-classify as “White Egyptians” –even though they themselves would most certainly be regarded as a non-white ethnic minority in a white majority country such as the UK or USA,” says Mahfouz.

Mahfouz spotlights a popular phenomenon not just in Egypt, but across the Arab World. The infatuation of many individuals with Western (mostly European and American) culture has them seeking to obtain a status of “whiteness” despite the fact that they will be regarded as “the Other” in Western countries.

The Arab World may have moved past occupational colonialism, but the region still seems to be infatuated with the West. Following colonial conquests across the world, European countries gained an abundance of hard and soft power –filling not only their national museums with Arab artefacts, but maintaining a sway over the minds of many.

History and politics stand as proof that after years of colonial rule, colonized countries will need years of recovery to regain their standing. This serves as one explanation as to why “third world” countries still fall behind the West.

The West, after centuries of domination and conquest, have gained their placement at the expense of “third world” countries. While we lag behind, they sit comfortably. It comes as no surprise then to see why many Arabs seem to regard them highly.

Arabs have become so infatuated with the West that they pine after fairer skin tones, bleaching their skin to resemble them. And this is where the problem lies: It feeds into a dangerous discourse where darker skin is an aberration and white skin is the exemplar model.

The phenomenon of the skin bleaching cream

Black skin in the Arab World has become synonymous with derogatory. The idea of white skin signalling superiority has become ingrained in the minds of many, further propagating Western racist stereotypes.

In efforts to steer away from black skin in hopes of achieving “whiteness,” Arab women have adopted the use of skin bleaching cream to brighten their skin tone.

Filmmaker Eiman Mirghani explored this phenomenon through her short film, The Bleaching Syndrome.

Throughout the making of her film, Mirghani found it difficult to find someone willing to speak to her in front of the camera. Towards the end, Mirghani explored her own relationship with her skin tone and bleaching creams along the backdrop of the region’s racist nature.

“I was first exposed to skin bleaching when I was 13 years old and continued to do it on and off for two years following. Skin bleaching can be extremely dangerous, as many of the creams can be detrimental to the human skin,” Mirghani tells Beirut Today.

“In Sudan, where I come from, people have home businesses in which they make these creams in their own homes. As a result, these creams can contain harmful chemicals like mercury or lead, which can be cancerous and lead to organ failure.”

According to Mirghani, the state later went on to implement laws to reduce the sales of these products, but due to high demand, consumers still find ways to purchase them. She likens the practice to the usage of makeup as it has become so normalized within certain societies.

“Like many places around the world, the MENA region largely upholds and values Western beauty standards, such as light skin, soft hair and light-colored eyes. This is mainly due to the fact that there is a lack of representation of people of color in this region, particularly in the media,” she says.

“Furthermore, people of color are usually stereotyped or wrongfully represented to be of a lower caste, ugly or lazy. These harmful representations have led to an increasing trend of skin-bleaching –particularly amongst women– to meet the beauty standards often shown in the media through white people.”

Only when Mirghani began to find her own voice as a young adult did she begin to realize the stereotypes underlying these beauty standards, before finally detaching herself from this culture.

The film ends on a chilling note, with Mirghani giving a monologue on racism in the region. She emphasizes the continuous usage of the word slave (“abed”) to describe individuals of darker skin tones.

On #BlackLivesMatter and unlearning racist practices

“This movement is starting many conversations across the world and making people question if racism exists in their own homes,” says Mirghani.

“So far, especially in social media, there has been a greater awareness of the racism that exists in the Arab World and people are starting to educate themselves on how to be anti-racist and giving the floor to black Arabs and Afro-Arabs to express the prejudice and racism they have been experiencing for years. It’s happening slowly, but people are no longer afraid to speak up.”

In unlearning racist practices, it is important to look towards the essential literature and to support black workers and creatives to aid in preserving the continuity of their practices.

Mirghani recommends reading Season of Migration to the North by Altayib Saleh, Race in Pre-Islamic Poetry by Touria Khannous, Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishnan, Foundations of Modern Arab Identity by Stephen Sheehi, and Black Morocco by Chouki El Hamel.

She herself looks towards the works of Khalid Albaih, Abdullah Al-Ameeri and Marwa Zain, three black Arab creatives, for inspiration.

Dismantling racism

Racism will not always assume the same explicit form as blackface, but can take on other equally horrendous shapes, whether they be structural or linguistic. The existence of an inherently racist structure such as the Kafala system continues to promote modern-day slavery, and the usage of words such as “abed” promote verbal abuse.

Moving forward, it is essential that we all reflect on our own personal practices and on the region as a whole. Racism is a structure: It occupies different shapes and forms, and it needs to be dismantled.