In March 2016, Lebanese officials came face to face with the largest case of human trafficking in the country’s history. The inquisitorial commission in Mount Lebanon raided super night clubs Chez Maurice and Silver in Maameltein and freed 75 Syrian women, some of whom had been there for over two years.

The story caught international media attention as journalists raced to break the news on the details of the ring’s operation. The ring leaders were revealed as Maurice Boutros Geagea, Imad Mahmoud El Rihawi, and Fawaz Ali Hasan, who had been running the ring for over 10 years at the time of the raid. The trafficking case took the country by storm, but media attention slowly died out until it vanished from public consciousness. Geagea, Rihawi, and Hasan remain at large.

Despite the story fading into the country’s cluttered media space, one person took note.

“I learned about the case in April 2016 like everyone else. I woke up, read the news, and was disturbed for a week. Then, I noticed that, in the mainstream media, it started fading into oblivion, just like every other piece of news in this country. However, it kept resurfacing in my consciousness,” American University of Beirut (AUB) Theatre Professor Sahar Assaf told Beirut Today.

As a result, Assaf conceived “No Demand No Supply: A Re-reading of Lebanon’s 2016 Sex Trafficking Scandal,” a documentary theatre performance under the patronage of the AUB Theater Initiative and in collaboration with NGO KAFA. No Demand No Supply ran from September 4 until September 7 at Zoukak Studio.

The story began to take shape as a result of the numerous sources that Assaf scavenged through. One thing, however, begged her attention. The media coverage of the incident was lacking one key element in the equation: the sex buyer.

“I wanted to tell these women’s stories, but I was also thinking of what I could bring to the table with these stories. People know similar stories, what’s new in what I’m telling? The buyers are also accountable. They commit criminal offenses. That is what I wanted to tell,” Assaf told Beirut Today.

The performance uses a 2014 KAFA study under the name of “Exploring The Demand For Prostitution: What Male Buyers Say About Their Motives, Practices, and Perceptions” as a blueprint for retelling of the Chez Maurice horror story. The study investigates a small sample of 55 men to explore the attitudes in which buyers of sexual acts view prostitution.

The study cites the population of sex buyers as “hard-to-reach” as it is not characterized by “a specific profile.” This reasoning is behind a character who Assaf calls “Mr. X” in No Demand No Supply. He has no specific socioeconomic, ethical, or religious background, but is merely the fifth, unseen character; the catalyst of the sex trafficking industry.

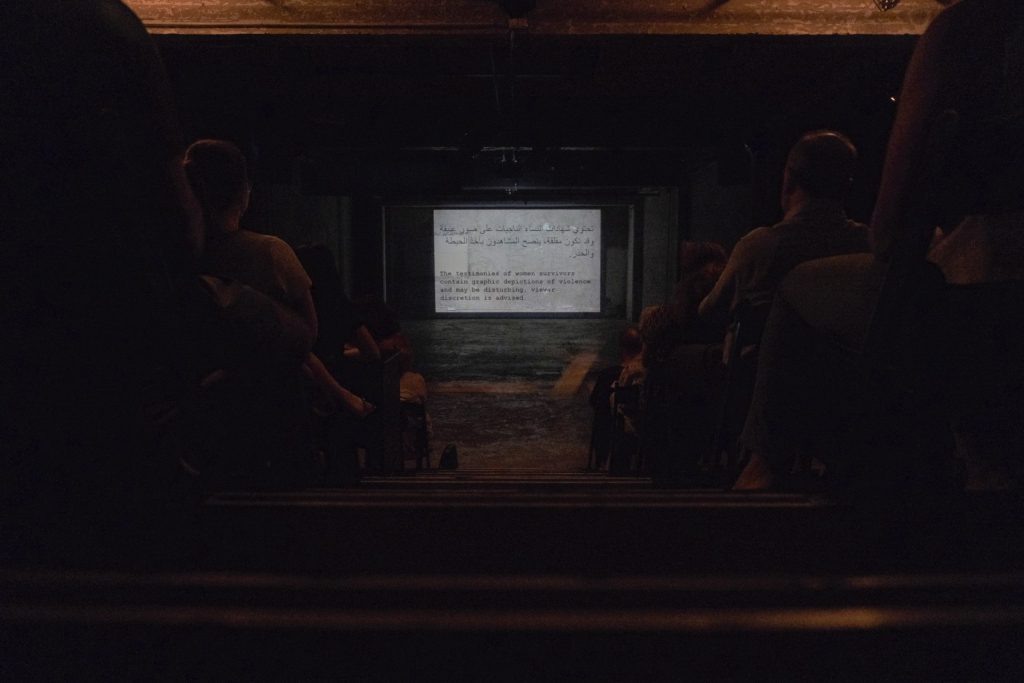

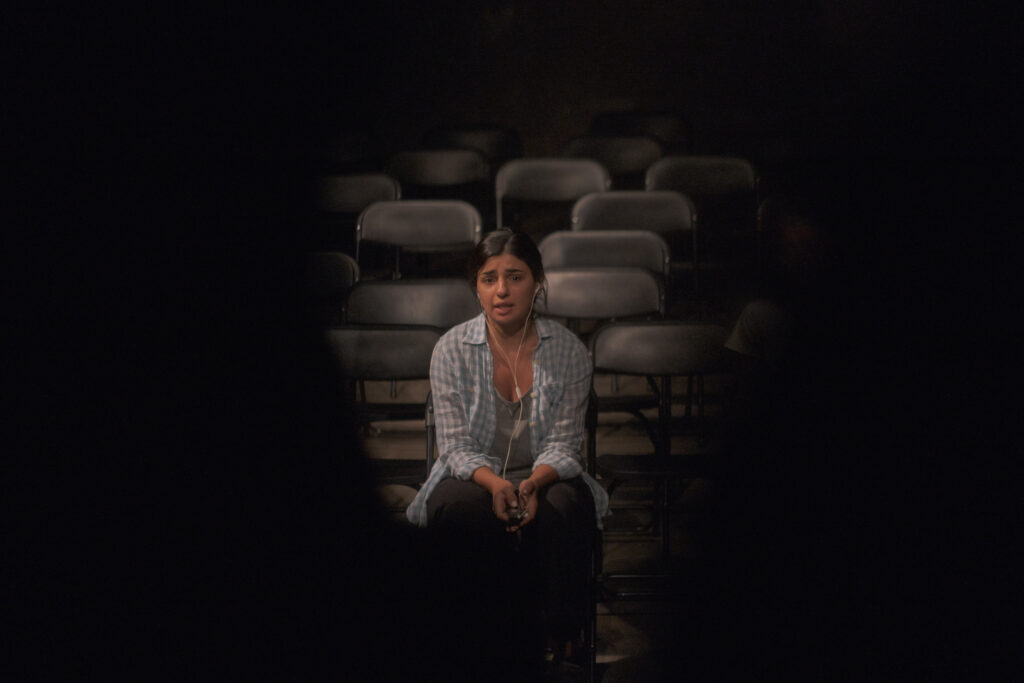

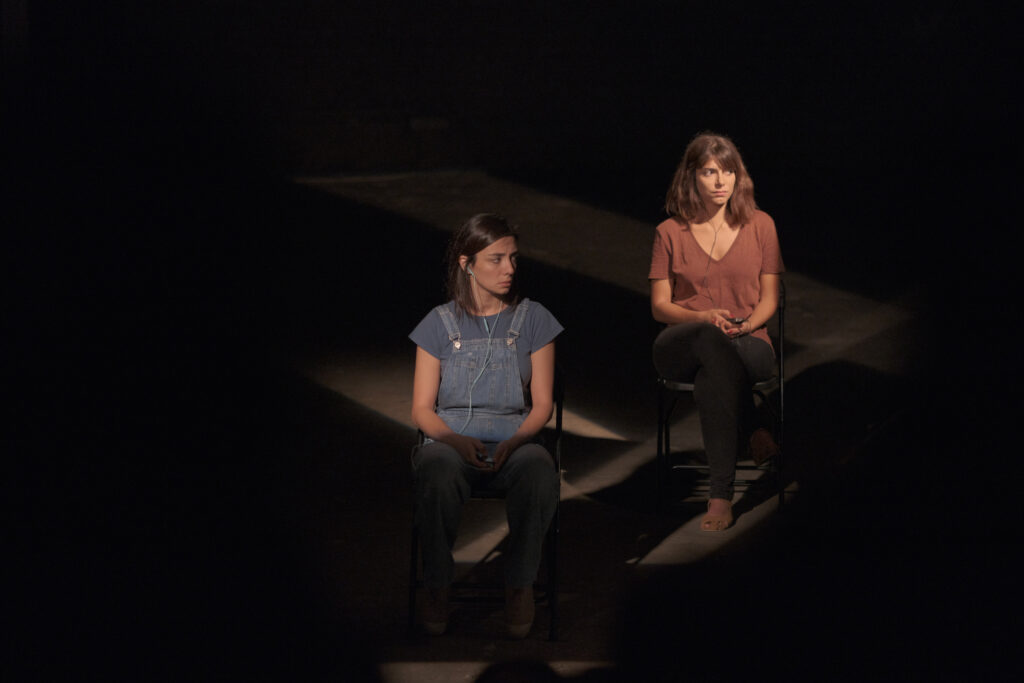

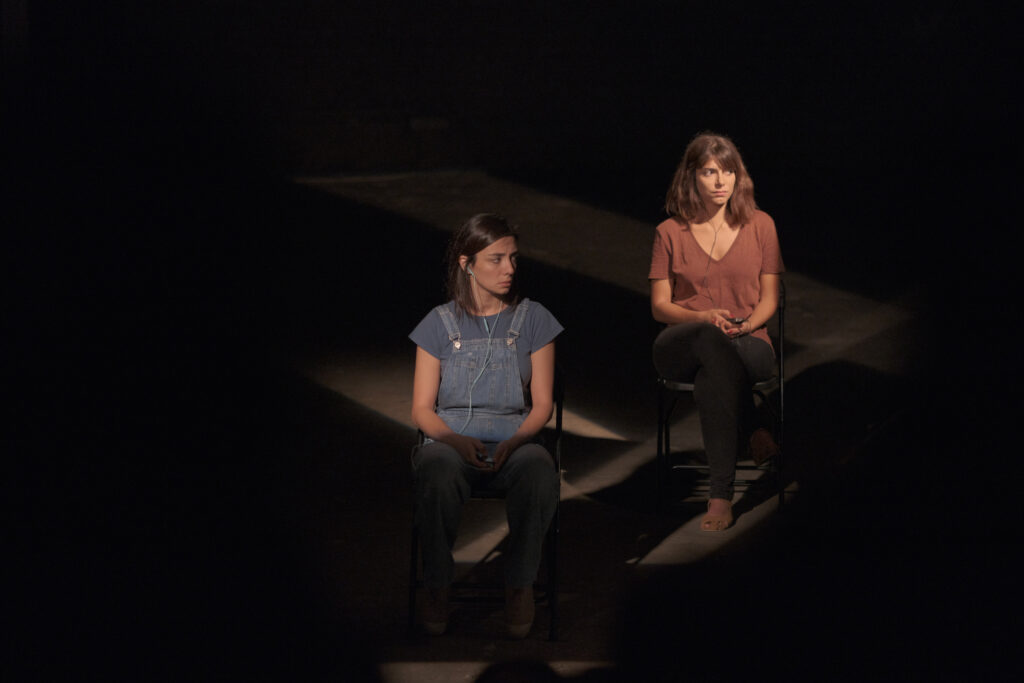

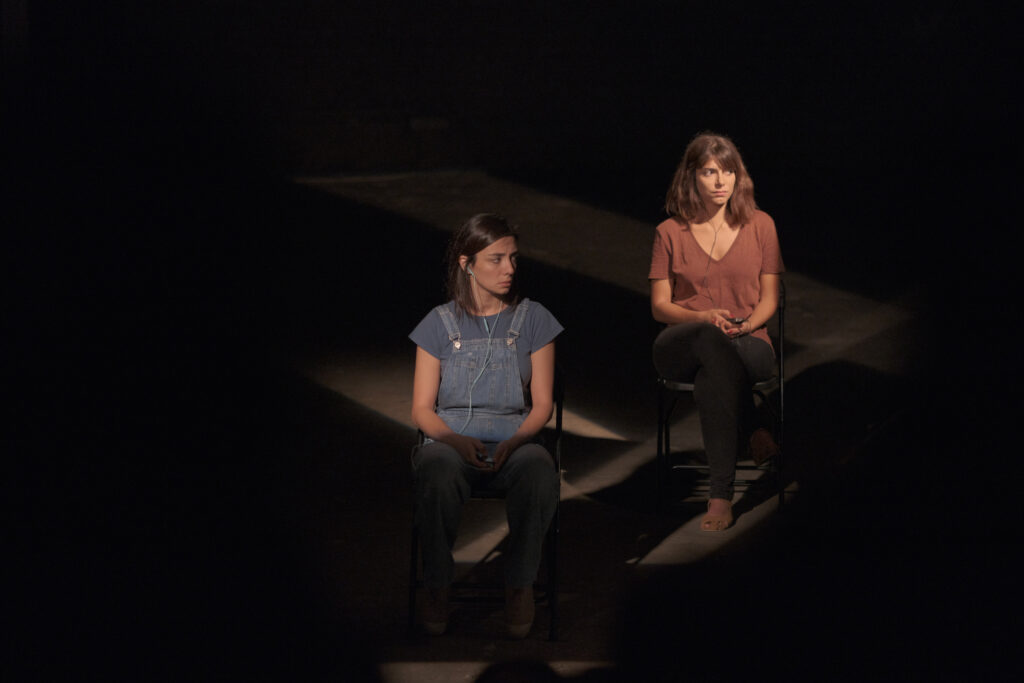

Using the recorded delivery technique, where actors repeat lines read to them through an earpiece, four actresses narrated the victims’ accounts under different aliases that were based on interviews conducted with them by journalist Sandy Issa and KAFA. In the background, Assaf took on the role of the narrator.

The ring constituted of 75 women working 7 days a week, seeing clients at least 15 times a day inside rooms with no access to sunlight or fresh air, at a rate of L.L. 50,000 per session. According to an article by The Telegraph, the ring was making an estimated monthly revenue of one million dollars from the services provided by the women.

Mr. X was a familiar character in all the women’s stories, and his interjections in the form of sound bites narrated by different voice actors left audience members uneasy.

“I’ve never asked, but no woman would be happy doing the work they do. There are men who force her to go into this work. And you know how men are, they shout and mistreat them,” said one Mr. X. “The girl is mine, I paid for her. At the end of the day, it’s her job, and she has to accept whatever I ask of her,” said another.

According to the study, only 5 out of the 55 men recognized that the women they are buying services from are subjects of human trafficking, an awareness that does not stop them from engaging with prostituted women.

“We should start calling them prostituted women, not prostitutes. If there is no prostitutor, then there [is no prostitute]. My intention was to show the discrepancy in numbers. When we talk about prostitution, or sex work, there is a huge difference in numbers between [the buyers and the available women],” Assaf explained. “According to the International Labor Organization, it’s a 150-billion-dollar industry per year. It’s happening everywhere.”

No Demand No Supply ended on a somber tone. Assaf informed the audience that the government has so far failed to provide any considerable support or protection for the women involved in the ring, leaving them vulnerable for future exploitation.

According to The Legal Agenda’s survey of cases of human trafficking in criminal courts, the Chez Maurice case was an exception to an ongoing occurrence in Lebanese courts where women practicing prostitution are prosecuted in joint trials with procurers of human trafficking. Such rulings usually rely on whether the court considers the case a felony of human trafficking or a misdemeanor of facilitating or benefitting from prostitution.

Three years after the incident, the case is still open in court. Hearings have been postponed multiple times due to the Chez Maurice and Silver business partners’ failure to appear in court. The next court hearing is on October 29, 2019. Assaf is hopeful that the performance will not only create awareness around the Chez Maurice case, but also empower public opinion to reach a fair verdict for Rihawi, Geagea, and Hasan.

“I would hope that we would be able to perform before the next court hearing. I want people to turn on the TV one day and see that a fair verdict has been reached,” Assaf said when asked about her future plans for No Demand No Supply.

“I would also hope that we can perform in schools and universities, because I feel like if we can reach out to these young men before they have their first experience with a prostituted woman, we would be able to change the culture or instigate a discussion.”

No Demand No Supply is showing on October 6 at Zoukak Studio as part of Beirut Pride’s third edition.