A video shows a row of Ethiopian women lying down to sleep on the pavement in the middle of the night, covered in thin blankets with suitcases of personal belongings behind them. The migrant domestic workers were stranded for weeks outside the Ethiopian Consulate in Hazmieh, Lebanon after being abandoned by their employers without months of pay.

Two nights ago, after an outcry of anger from local activists on social media, the Ministry of Labour secured a hotel as a temporary shelter for the Ethiopian workers and pledged to investigate and take the necessary measures against their employers. But more women continue to arrive to the closed embassy.

“Madame threw me here on the street,” one of the migrant workers stranded outside of the embassy told Beirut Today, on condition of anonymity. “She doesn’t have any dollars so she doesn’t want me.”

As the worst economic crisis that Lebanon has witnessed in decades intensifies, more and more reports of domestic workers facing abuse and being let go of are emerging. But this is not a one-time incident. Their plight is the result of Kafala, the modern-day system of slavery that governs the work of foreign domestic workers in Lebanon and seven other Arab countries.

“There’s no money and dollars, but [her employer] should wait,” told us another Ethiopian worker. “She shouldn’t throw her into the streets where there’s no food, no bathroom, no nothing. They put them in taxis and throw them.”

See also: Abolish Kafala: Lebanon’s domestic workers are stranded in the streets

Some women have been stranded for weeks. Last month, a series of interviews by Amnesty International highlighted their struggle.

“She didn’t pay me my last salary,” one told Amnesty. “She also said she cannot pay for my return ticket. She dropped me off here yesterday. The police officer saw me crying. He asked me for madame’s number. He called her asking her to come back and take me. She came back only to give me my passport and identity documents and she left again. I don’t know what to do. I want to go back home.”

Kafala gives employers absolute control over migrant workers

The dangerous Kafala system reared its ugly head in another way just last month in Lebanon, where 400 migrant workers accused waste management company RAMCO of serious human rights abuses. The company had cut their wages and had stopped paying them in US dollars since November 2019, giving them their slashed salaries in Lebanese liras instead. The local currency has lost more than 60 percent of its value in the past six months.

“I used to transfer my salary to my family in Bangladesh in dollars, but now that I’m getting paid in Lebanese pound, I have to exchange it at the black market rate, which amounts to very little,” an anonymous worker told Middle East Eye, which also added that his slashed $120 salary was now worth $42 in Lebanese liras.

The workers’ weeks-long work strike was met with intense violence from Internal Security Forces before RAMCO agreed to slightly raise their salaries again.

The history of Kafala in Lebanon shows horrendous human rights violations, although many are illegal in the country. Lebanese law forbids employers from confiscating the passports of migrant workers, but it’s still very commonly practiced in the country. Many of the Ethiopian women currently stranded in Hazmieh say they were forced to leave without their passports and personal belongings.

Under Kafala, the fate of migrant workers is bound to the employers who sponsor them. Their contracts can only be terminated with the consent of their employers. If for any reason, their contract is terminated by the employer, migrant workers become undocumented and illegal residents who can be arrested, thrown in jail, or deported.

“Giving employers this level of control over workers’ lives has led to an array of abuses that Human Rights Watch has been documenting for years, including non-payment of wages, forced confinement, no time off, and verbal, physical, and sexual abuse,” writes Aya Majzoub, a researcher from the international rights group.

Migrant workers are continually dehumanized

When hunting for family homes in Lebanon, it’s not uncommon to stumble upon rental listings that include a “Maid’s Room” that’s windowless and barely big enough to fit a single-sized bed. The migrant women who occupy these rooms are more than often underpaid, have no days off, and subject to the whims of their employers.

Documented cases of abuse and neglect reflect an intense amount of fear carried around by domestic workers. Advocacy group This is Lebanon tells the story of Halima, one woman from the Philippines, who was interviewed by the Philippine embassy in 2017 about how she was being treated by her employer (Ibtissam Saade).

“I did whatever she told me because if I didn’t, she would kill me,” she says in a video. According to This Is Lebanon, her employers prevented her from making even a single phone call to her husband and three children for ten whole years. They also locked her in her room at night. Without access to the toilet, she was forced to relieve herself in her room.

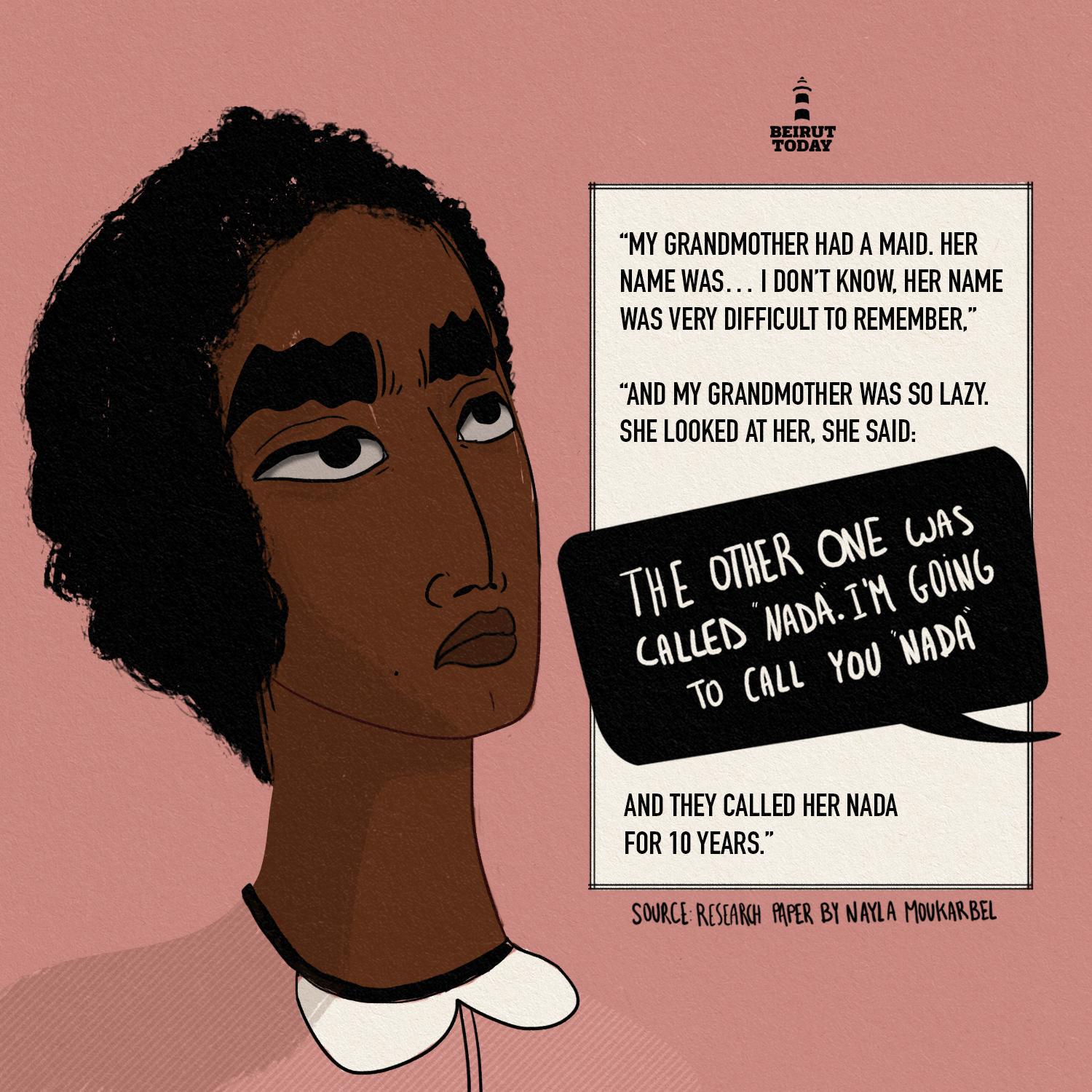

Lebanese employers exercise unmitigated power over migrant domestic workers, going as far as re-naming them when they find their names are too long or difficult to pronounce.

“My grandmother had a maid. Her name was… I don’t know, her name was very difficult to remember,” says one Lebanese employer interviewed for a research paper by Nayla Moukarbel. “And my grandmother was so lazy. She looked at her, she said: ‘The other one was called Nada I’m going to call you Nada.’ And they called her Nada for ten years.”

Lebanese employers dehumanize migrant domestic workers, and Moukarbel’s interviews acknowledge that. They also show that employers consider their treatment to be acceptable, necessary, and the natural order of things.

“They do not feel guilt or shame, and if they do, they convince themselves that, in the end, they are doing their housemaid a favour by employing her and that, they, as ‘ideal employers,’ should be thanked,” comments Moukarbel in her paper.

Meanwhile and more recently, one after the other, Arab celebrities rushed to wear blackface in support of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US. When flooded with angry comments about their gestures being racist, some released statements saying their intentions were good and their actions were not wrong. Others quietly deleted their social media posts to avoid the controversy.

Before we show our support to the George Floyd protests, shouldn’t we be vocal about abolishing our own racist Kafala system? Or does Lebanon’s history of colonization mean that our support for Black people ends when they’re not from the West?

Being comfortable enough to wear blackface indicates ignorance about a difficult history of stereotypes and violence against Black people, which could be redeemable with better education and radical cultural shifts in Lebanon. But refusing to change when confronted by the people you’re hurting indicates you don’t care enough to educate yourself on their opinion in the first place, despite what you openly say.

In Lebanon, the conversation starts with abolishing Kafala and protecting migrant workers’ rights with clear laws but it should hardly end there. The discussion must expand to humanizing, unionizing, and bettering the lives of the workers –Ethiopians, Sri Lankans, Syrians, Palestinians, and more– who come into our country to make a living and feed their families but regularly end up leaving back home in body bags.