The global economy has been struck by an unforeseeable shock. The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has spread across borders as confirmed infected cases have been reported in almost every country in the world.

In early March, The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the outbreak a global pandemic. Since then, governments around the globe have shut down non-essential businesses and halted trade operations. Educational institutions have shifted to online learning as lockdown policies and curfews have been set up. The typical supermarket has now reduced its opening hours and limited purchases per person with the emergence of a global trend of panic-buying.

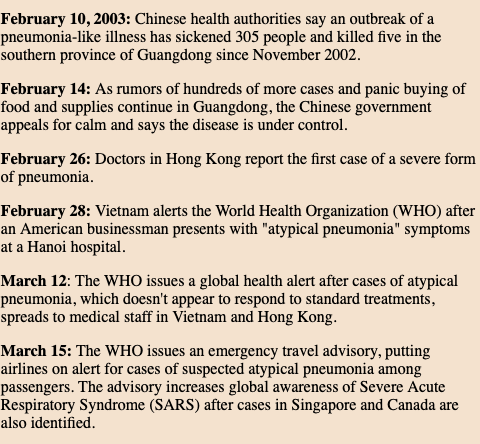

Panic-buying is not an unfamiliar occurrence and has been witnessed before. In 2003, when the Severe Accurate Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak spread, panic-buying was evidently common. This CNN-published timeline dates back to February 2003, another time when the global economy was similarly shaken by a global health crisis.

Pandemics cause economic disruption. But they can also do a lot more.

Historically, the global economy has been torn apart by shocks, be that war & conflict, political tensions, or pandemics. The sort of shock and the intensity of its impact vary from one country to another as well as across periods of time and economic sectors.

When a virus starts spreading, states gradually roll out lockdown policies and curfew mechanisms, through either reducing business hours or completely wiping out any.

The impact of quarantining on businesses is discernible: increased labor layoff, reduced productivity, as well as closure and liquidation of many small to medium businesses.

In general, a loss of economic activity as a result of isolation measures triggers an economic freeze in an effort to combat said debilitating virus. It is a trade-off and governments are gradually yielding to the following alternative: numb the economy right now with the aim of mitigating the health crisis and worry about the cost of doing so at a later stage.

Incorporating mortality rates into such an analysis is also vital. Assessing the impact of a sizable shock on per capita GDP, labor force, and income levels is certainly of great importance. However, it coincides with another vital dimension: human life.

If we assume an economic model where governments willingly decide to keep businesses open for a wide time interval, we are expunging the boundaries between the viral infection and society. The virus is being set free.

This could mean a remarkably high number of deaths especially if the said virus spreads fast and through diverse media –as is the case with the COVID-19 outbreak. The labor market will be hit strongly and significantly so, and a wide base of consumers and investors will suffer.

If population shocks are neglected in our impact analysis, a causal understanding of the size and intensity of the effect of a pandemic on an economy would be difficult to capture due to underestimation. With travel bans becoming common practice, the economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak is proving to be exponential.

The Virus has the economy limping

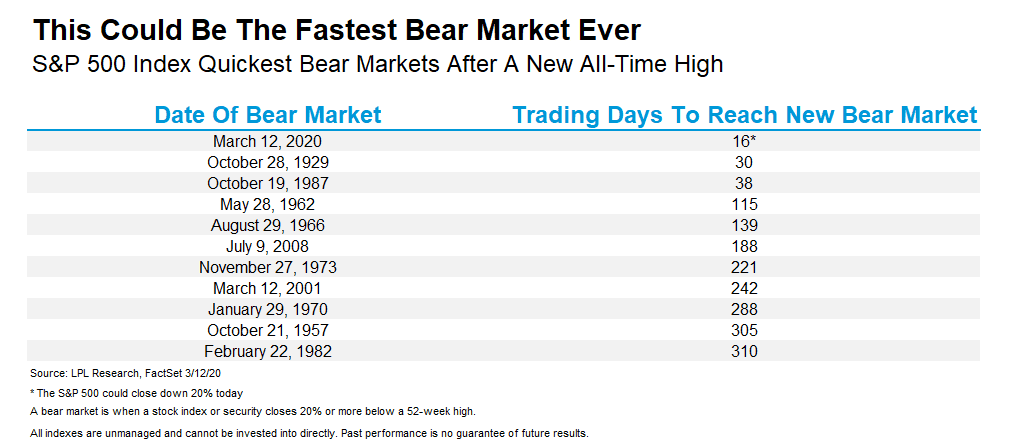

The Great Depression slowly fed off the world economy. It was years until the impact of the shock clearly materialized. It took the COVID-19 virus only a couple of weeks to rip through global stock markets.

During the Great Depression, stock markets collapsed by at least 50 percent, which consequently triggered bankruptcies, unemployment and an overall global panic. In just two weeks, in early March, signs of investors becoming more risk-averse surfaced as US stocks plummeted into bear-market territory, an occurrence that has last been witnessed on the Black Monday of 1987. A bear-market territory is characterized by stocks falling off their peak level by 20 percent at minimum.

Economic channels under the fire

Clearly, there is a lot of fluidity and uncertainty when it comes to the effect of the outbreak on economic sectors and channels. This is ultimately because it is a new virus and its characteristics could alter. We are learning by doing.

Testing capacity is important and anchoring in this economic crisis. Testing capabilities of some nations remain unclear which implies that “official” numbers on infected cases might be biased downwards.

In order to assess the economic impact on countries, especially those that have been hit most or those that are vulnerable, it’s important for economists to accurately depict the size of the crisis. And to do so, we need to have an accurate depiction of the total number of people affected, or an estimate of that.

The latter is applicable to developing and war-ridden countries with barely any resources or technologies, not to mention funding for testing kits.

Most importantly, the rate at and modus operandi through which governments act says a lot about which economic channels are going to be impacted most and how.

Clearly, countries like the US and the UK, delayed their policy responses such as imposing a full state lockdown or university closures. Policymakers and leaders in said countries are now left helpless as the number of infections and deaths continue to exponentially rise.

The COVID-19 outbreak poses a simultaneous shock to both supply and demand. And that’s part of why it is threatening. Following travel bans and event cancellations, factories closed down, services have been cut off and global supply chains were disrupted. Government responses, coupled with media intervention, have triggered a simultaneous shock that has negatively impacted consumer confidence.

If we look at China alone as a baseline measure, a shock to demand will destabilize global markets, seeing the major role the country plays in the world economy today. This will plunge global GDP even more. Economies that are service-oriented will witness a strong blow.

Central Banks and financial analysts have exhausted their most powerful instruments in recent years, meaning that the resources many governments can rely on to stimulate the economy are extremely limited.

The impact of the outbreak will not be symmetric across sectors. Certain sectors will actually benefit from the crisis (think of panic-buying as a common trend) in comparison to other sectors (like the tourism or hotel sector).

For example, a drop in Chinese tourists, which evidently trigger spending increases, will heavily affect the global tourism sector. According to the World Tourism Organisation, China has had the largest international tourism expenditure since 2014. China is also a major importer and exporter of commodities (being the world’s largest exporter), according to the World Trade Organisation.

A shift in trade patterns will likely affect income distribution and poverty figures in countries either reliant on China for products or for intermediate inputs. So, a hit to China’s economic operations is proving to be a hit to the world.

Global supply chains have encountered an unprecedented shock and it will take time to recover. The prolonged disruption will alter cost structures in the manufacturing sector. For example, watches and automobile production rely on a healthy global supply chain system, within which China is a major player. Amidst lockdown, those producers have been harmed and left in the dark.

The pandemic is a hit to economies and communities that rely on remittances. According to the World Bank, remittances are estimated to have injected no less than $700 billion to the global economy. Expats might be inclined, for the sake of self-survival, to alter money-sending habits.

Evidence suggests that the outbreak has limited the extent to which people in poverty, particularly in developing nations, receive financial support from abroad.

Some analysts, however, hope that this might still signal a scenario of a V-Shaped Recovery. What is the latter telling us in the context of this outbreak?

A recovery as such takes place when an economy witnesses a strong and consistent economic disruption (an economic decline) –which is in line with current economic predictions attributed to the outbreak– followed by a speedy and long-lived recovery.

As you might think, a ‘v-shape’ is visualized by graphing the economic health of a country, which is constructed using particular indicators/variables such as unemployment rates and GDP. In a scenario of V-Shaped Recovery, an economy declines starkly and sharply but quickly recovers, triggered by enhanced economic activity such as increased consumer expenditure.

In other words, markets are revitalized.

Turkey tells us a similar story. Following a fast-paced contraction of domestic and foreign demand, the country was dragged into a recession where its GDP plummeted by 15 percent year-over-year in the first quarter of 2009. Nonetheless, a recovery started to take shape when GDP increased by 6 percent in the fourth quarter. However, this analysis or prediction might not be as straightforward for the crisis at hand.

Are We Going to Witness a V-Shaped Recovery Post-Outbreak?

Evidently, there were periods in the past when countries were hit by sharp declines in economic figures, such as during the global financial crisis, but still managed to soar high after. For this particular crisis, it is unlikely. Here’s why.

It’s often tricky, when analyzing economic responses to crises, to look beyond the numbers: the number of jobs lost, fluctuation in market prices, stock market figures, interest rates, rate of infection recovery, mortality rates etc. We need to examine the social and psychological remnants of the outbreak, with a particular focus on consumers and businesses.

For a V-Shaped Recovery hypothesis to be validated, we rely on the assumption of increased spending. Admittedly, when social distancing measures are relaxed and a sense of normalcy (however that is defined in the post-outbreak area) is restored, one might expect increased spending.

At the minimum: restaurants, cinemas, and other entertainment venues will cater for a sharp increase in demand. Should we truly expect people to rush into spending? How would a typical consumer value queuing in Burger King, post-outbreak? Is a pandemic-induced deprival from entertainment or leisurely activities strongly correlated with an overwhelming increase in spending as social distancing measures diminish? Unlikely.

The economic contraction we’re witnessing, as financial markets collapse, would not fit into a v-shaped recovery –a scenario economists and governments have been rooting for.

In practice, a stark shift in saving patterns amongst different economic actors can be foreseen.

The outbreak has so far emotionally scarred us in unimaginable ways. Poor family members are faced with the threat of starvation or neediness. They have to carefully calculate their consumption of food on a daily basis to meet a survival cut-off. Panic buying as a practice is a privilege which they don’t necessarily have access to. This is a lived reality of people who are running out of funds to pay dues such as rent or schooling.

The outbreak means so much more than a drop in national GDP to the majority. In lockdown, an old household member has two major worries if they do end up contracting the virus. There is the possibility of infecting other members and putting their lives at risk. And there is the reality of not being able to afford healthcare expenses. This can’t be separated from the sense of uncertainty societies are collectively experiencing.

If you do sense symptoms, access to testing equipment or hospital admission is not guaranteed. Global health systems have proven to be unprepared for a crisis of this gravity. That, on its own, is troubling.

Businesses have a similar story to tell. Working from home proved effective for some, but for others it is not an option. When governments unilaterally implement lockdown and curfew policies, this implies income cuts for informal workers and other underprivileged, low-income earners such as those working in construction.

It becomes far more problematic when aid packages and social safety nets are not at all factored in to support those groups of people; and that’s a lived reality too. Even well-off businesses with high investment in technological innovation will likely observe a behavioral shift reflected in costs.

More money will be injected into health insurance plans, paid sick leave, and less money injected into physical meetings and other business activities which have now become inferior. The global trend of online meetings might not cease even after the outbreak does.

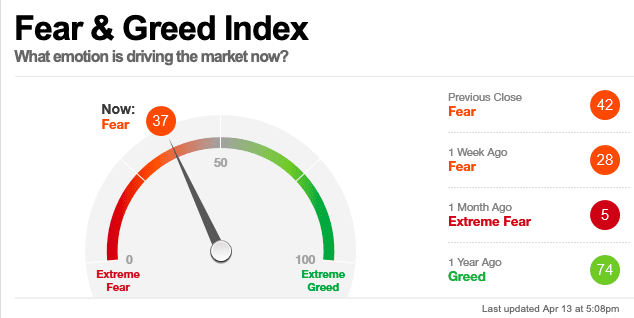

The fact that financial markets are highly volatile with a stark drop in stock prices has built up fear and uncertainty amongst different economic actors. CNN Business has set up a Greed and Fear Index (see here), based on several indicators such as market volatility, which regularly updates. The scaling is between 0 (Extreme Fear) and 100 (Extreme Greed). The current score is 37 and was lower in previous days.

On April 2, the United States of America’s Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) completed a preliminary estimate of the budgetary effects of COVID-19. It is expected that US GDP plunges by 7 percent in the second quarter. In the linked report, it is reiterated that such estimates are not final because of the rapidly changing nature of events attributed to the outbreak.

Economists predicted even worse measures than the 2008 crisis. The United States provides a strong case as to why a V-Shaped Recovery is unlikely. It was only a few weeks back when around 10 million individuals filed for unemployment benefits.

The anxiety attributed to losing a job is mounting and is yet another reason why it is unlikely that consumers will rush into spending once the lockdown is over.

We are looking at possibly the worst unemployment level to be recorded in history.

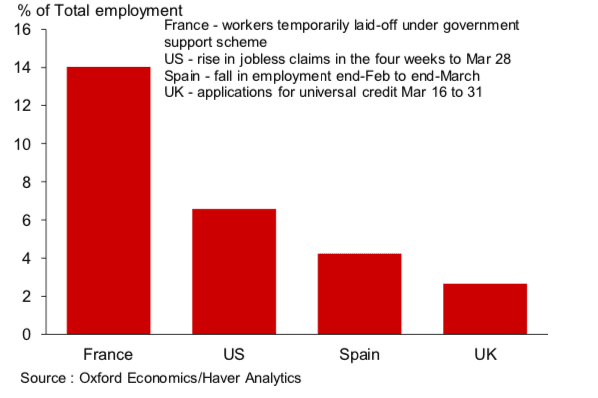

Even though certain countries have succeeded in flattening the curve, such as China, this doesn’t relieve the world from looming economic costs. Oxford Economics’ researchers have attended to the issue of “labor shakeout” in a recent study. During the last two weeks of March, over 900,000 universal credit applications were received in the United Kingdom, which could signal a potential loss in jobs, confidence, and income in the coming months. This is becoming a global trend.

Scientific predictions of the outbreak possibly emerging again in the future is yet another setback, because this will entail more social distancing, more business failure and consequently risk-averse behavior. We will see people more inclined to sustaining their “own safety nets” as this is a troubling reality some generations across the world might have never witnessed before.

The collective impact of the outbreak on our psyche is undeniable. When this is all over, and as soon as consumers are formally allowed to work again, they will be naturally guided towards saving more; indulging in a culture of thrift.

Consumers will spend less on travelling and gym memberships. The psychological shock will also extend to transportation habits, where it is less probable that car owners will use public transport, in an attempt to avoid gatherings. It is for all such reasons and more that a quick economic recovery is unlikely. At minimum, we will witness a decline that is sharper than that of the financial crisis

What are Governments Doing For The Economy?

The total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases have surpassed 1 million and the global economic repercussions are becoming graver as each day passes. If we are to witness a speedy economic recovery, governments need to provide adequate fiscal, monetary and public health responses.

Governments should enhance the availability of and ensure accessibility to testing kits as well as enforce stricter lockdowns.

The obtainment of a vaccine is not at close reach. So, governments need to put additional effort into laying out treatment options and make those accessible.

Claire MacPherson, Economist at the Department for International Development (DFID) of the UK Government, spoke with Beirut Today about what governments can and should do to combat economic contagion.

“It is expected for global growth to be halved. That’s a possibility. To keep the economy afloat, governments can rely on several fiscal instruments such as quantitative easing, direct credit easing, tax holidays, and liquidity provisions,” she said. “Central banks would reduce interest rates to encourage investment. Additionally, governments should support households by issuing government guarantees of personal loans or mortgages as well as support financial institutions/banks to be able to accomplish this.”

Fiscal measurements are as important.

“Fiscally, tax relief should be handed to individuals and households. Subsidies and transfers should be laid out to support those who lost their income. We can also see more generalized measures such as strengthening social safety nets and protecting the vulnerable through employment benefits.”

Indeed, those are policies currently being implemented by several developed countries in Europe and beyond. The Danish government, for example, agreed to cover employees’ salaries at private companies affected by the pandemic to ensure no one gets laid off. The agreement is to take on 75 percent of said salaries which would amount to around $3,000/month. However, it is important to note that this is a scenario we are unlikely to witness in low-income countries with restrictive resource packages.

An economic downturn will disfavor those who are in poverty and those who require access to regular income.

We must also consider economies which are communitarian, such as in multiple African countries, where production processes are not individualist in nature. Communities come together to produce and sell. And governments need to cater for the needs of those communities too.

“From a public policy perspective, everyone liable to lose their income should be supported. Ideally, you would need to boost social safety nets and fiscal stimuli where possible,” described MacPherson. “Equally important is monetary policy. This should be considered to prevent further financial tightening and also to illicit confidence. We need a broad range of policies, not just focusing on the health side of things.”

Most developing countries rely on international aid at times of crisis. Whether the international community is doing well on that front or not is worth examining. Are development actors capable of supporting poor nations today?

International donors active in development aid recognize the huge need for support required by developing nations at times of crisis. Let’s have a look at Yemen. The country is war-torn and operates on fragile and unequipped healthcare facilities. A few days ago, the government confirmed its first coronavirus case. Simply put, the system is not well equipped to combat a global pandemic. It will need the support.

MacPherson explained that DFID has been active in Yemen and has programs that have been able to help out. However, she does point out that there remains a challenge.

Countries which are in great need but don’t maintain strong relationships with the UN or large international donors will witness a slower flow of support.

At times of a pandemic, there is also the issue of public pressure, when citizens become less attracted to the idea of their governments spending so much on overseas aid. And that’s exactly why raising awareness on the gravity and the global nature of this crisis is of extreme importance.

The COVID-19 outbreak is normalizing the idea of globalization and interconnectedness amongst countries across all levels of development. But it has also managed to bring to surface the toxicity of class struggle often clouded by political propaganda and ingenuine diplomacy efforts.

To better monitor how different governments have been responding to the economic crisis, the International Monetary Fund produced a lively tracker.

The Coronavirus is on a mission to shake our moral compasses

The thought of “favoring your life over anyone else’s” which you might have recently been pondering is not entirely strange in a state of panic. It’s your moral compass reacting to new circumstances.

World leaders are debating the importance of human life in the face of crashing financial markets and withering economies. It should be clear by now that the economic system put in place, purely based on capital production and capitalist ideals, has failed miserably.

Our business transactions and activity managed to destroy the boundaries between the natural and social order giving birth to pandemics and diseases, which we are now battling on almost every front.

The failure of governments to adequately respond comes to show how unprepared our public health systems are –and we are being forced into an inhumane debate: save lives or maintain profit.

Policymakers, politicians, business owners and the typical citizen have been forced into a battlefield. The reality, however, is that we’d be in extreme luck if we come out of this with a surviving economy and public health system. And that’s an unlikely scenario, considering the economic impact of previous public health emergencies.

SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome): A Case Study

The potential economic effects of COVID-19 might be better understood when we look at how the global economy responded to the SARS outbreak, its circumstances and what it means for us today as a pandemic that emerged more than a decade later.

Which countries were hit? How long did it last?

In 2002, SARS, a form of atypical pneumonia, was declared a health threat by WHO. The outbreak, which originated from China, reportedly infected 8,000 people and killed over 700 at the time. It quickly spread to several Asian countries and other countries, such as the United Kingdom and Canada. It hit a total of 26 countries. The outbreak was fully contained in July 2003, following social distancing and isolationist measurements.

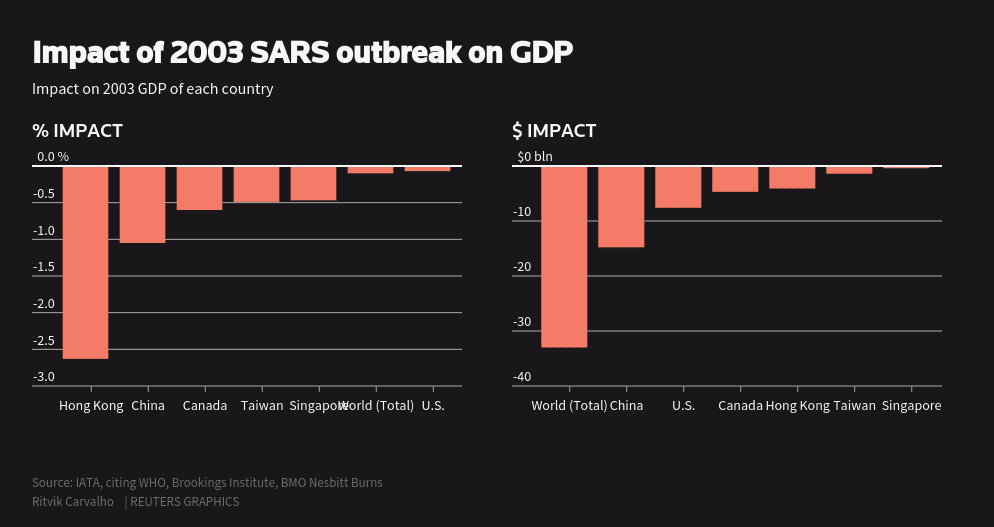

The SARS outbreak caused China’s economic slowdown in 2003. The growth dropped from 11 percent year-over-year in the first quarter to around 9 percent in the next quarter. A study attempted to estimate the economic impact of the SARS outbreak on the global economy. It estimated an economic cost of around $40 billion.

Similar to the COVID-19 virus, the SARS-induced disruption caused an adverse demand shock with increased fear of contracting the virus. This led to a sharp drop in confidence and business activities including travel and other investment operations.

It can be argued that the economic costs of coronavirus could be even more amplified. This virus has hit way more people than SARS did and has affected almost every country in the world.

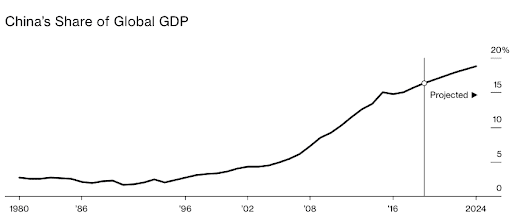

Additionally, the economic contribution of China, the country from which both viruses emerged, to world growth is much higher now than it was in 2003. The contribution of China to global GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund, stands at around 20 percent –more than double its share in 2003). The economy is going through extremely vulnerable times and it can be argued that our financial system is not immune enough to a shock of this intensity. Accordingly, the assumption that we are heading towards a global recession is not far-fetched.

Bloomberg Business reports that sectors affected in the 2003 outbreak like restaurants and entertainment service sectors now comprise 54 percent of GDP, an increase of 12 percent since 2003. It is also worth noting that COVID-19 hit China during a period of peak consumption levels.

Any economic analysis of the current situation should take into account the scope and timeline of the public health emergency –in other words, assess different scenarios. If social distancing is a short-term policy response, then we would assume a quick economic recovery in the second quarter or so.

This is where the comparison gets interesting. Lockdowns of this sort were not common in 2003.

And realistically, seeing the exponential spike in confirmed cases worldwide, it is unlikely that lockdown is short-term.

The 3-week window for the UK’s lockdown was supposed to end this week, however it remains imposed to date. This means economic growth will be hit with more disruption and slowdown in coming months.

China’s service sector, which has amplified post-2003, will now receive a strong hit and will likely destabilise the global economy. With a faster spread and more affected region to date, COVID-19’s expected economic impact is going to be global and governments need to respond quickly.

Should we really rely on the SARS outbreak to make conclusions?

There is so much benefit in analyzing the economic impact of the 2003 outbreak to make sound conclusions about this one. However, our analysis might be error-prone due to endogeneity concerns.

When the SARS outbreak established its grounds in China and neighboring countries, the world was going through an economic slowdown. It was a period of political tensions, including the Iraq war, and market fluctuations amidst increased oil prices.

The fact that China comprised only around 5 percent of global GDP is worrisome. It was not considered an economic powerhouse and thus, the impact today can be difficult to capture due to such a stark difference.

Spillover effects need to be accounted for given the current structure of the world economy: economies are extremely interconnected and thus, national economic impacts are not still. They are mobile.

The previous macroeconomic fluctuations that were happening alongside the emergence of the virus in 2003 might mean that our estimates of the economic impact of SARS are probably biased. Economists would need to better model, as the situation escalates, in order to come up with highly accurate conclusions with so much at play for the time being.

It is important to reiterate that the world has indeed been hit by tough crises in the past. This includes our modern history. However, the fluidity of the current public health emergency and the possibility of seeing the virus mutate and resurge in forthcoming periods makes our predictions extremely volatile at this point.

Our policy responses and instruments should be constructed in line with variations in factors attributed to the virus. To do so, economists, policymakers and epidemiologists should work more closely for a coordinated, well-informed and successful response to be materialized.

This is particularly vital for countries like Lebanon, where citizens are living through a broken financial system, high levels of poverty and unemployment, wide income gaps, and nationwide civil unrest at a time when public sector institutions have become festered with corruption and mismanagement. The shortage in US dollars has exacerbated the financial crisis and brought policymakers to their knees.

The government recently drafted an economic plan, which is highly dependent on the IMF’s support and privatization plans, through which they seek to reduce the debt and tackle corruption.

If the world’s most powerful economies have entered a state of panic and uncertainty due to resource shortages, can we still assume that a country with an extremely compromised infrastructure, a huge refugee population, and overarching insecurity, will manage to save its people amidst a global, life-threatening pandemic? We will have to wait and see.