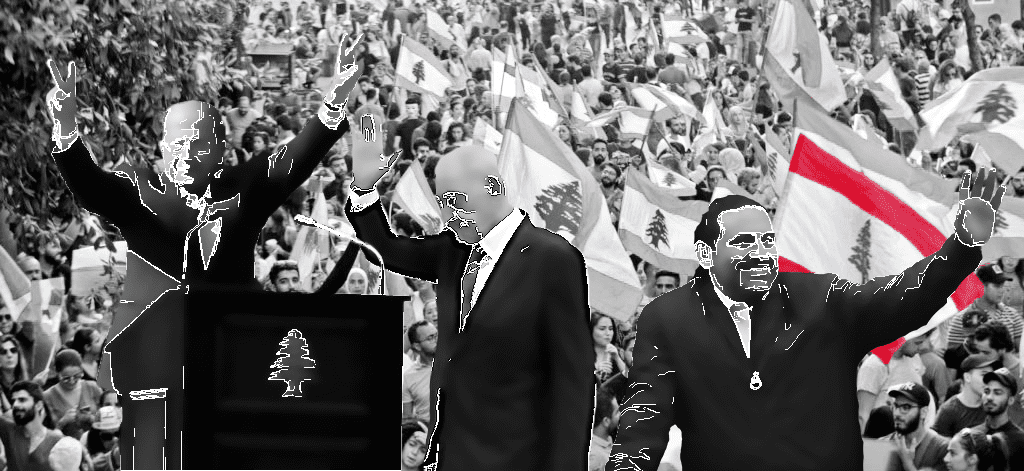

With the revolution entering its fourth week, Lebanon’s protesters continue to mount pressure on the current political establishment. Angry protestors are fed up with the political system, with calls for its end remaining one of their core demands.

A power sharing government has historically proven to be inefficient in the country. Any call for change that does not take into account the need for a conclusive government only serves to promote cosmetic measures that do not tackle the essence of the problem.

The power sharing agreement under which Lebanon is governed was agreed upon in 1943, three years before the country’s independence. The national pact, a non-written agreement attached to the constitution, incorporates Lebanon’s 18 sects into an all-inclusive political and social order. The pact that was intended to create the mechanisms necessary for a ubiquitous state has led to its demise.

What we are seeing today is people rising beyond their political, religious and social divides to voice their discontent with a ruling class that keeps regenerating itself since the end of the civil war. People’s resilience in the face of a ruling autocracy have signaled a breakthrough into a new era –the broad lines of which include an end to the sectarian political order, but the mechanisms to achieve that remain largely ambiguous.

The consociational form of governance presents a major obstacle towards the realization of a functioning state. Consensual politics has given rise to governments muddled with political rivalries and contradictory agendas, all under the pretext of inclusivity. A clear demarcation between the majority and opposition needs to be made.

Passing resolutions that please the whims of all political parties is a mere political fantasy. With a consociational political system, the resignation of a political faction renders the government unconstitutional as it is deemed “unrepresentative”. It is a system which impedes progress, as it favors narrow party politics over national interest. .

A revised social and political pact has to come in place after three decades of political uncertainty and economic failure. Any new order should act as an embodiment of Lebanon’s diverse social and religious constituents vis-à-vis the 1943 agreement, but also suggests the need for a serious revisionist attempt as is reiterated by the hundreds of thousands on the street today.

The people have taken to the streets to say that the current political order no longer serves them. All sects have united in expressing their demise, discontent, and above all, disillusionment with the political class in its entirety. This begs the question of whether the problem lies within the sectarian nature of governance or with the form of governance itself, which is based on political consensus.

A blatant abuse of sectarian politics has led to growing anger over sectarian political system

Political leaderships have manipulated the system while establishing loyalties by offering social and economic safety nets.

The sectarian nature of the political system, as was introduced in 1943 and further entrenched in the Taif agreement, was meant to serve as an insurance policy for all minorities. The problem with that, however, is that sectarian politics has given rise to a sectarian political economy that took advantage of the system to further establish its power.

As a result of this accumulation, The Lebanese have reached a tipping point. However, this revolution did not start now. In 2015, The You Stink movement was a precursor for what was to come in October 2019. It signaled precautionary call for politicians whose corruption had also reached an unprecedented level as the garbage piled on the streets.

Protestors, fed up with the political establishment, are blaming the sectarian system for Lebanon’s ills. The root cause of the problem, however, is the abuse of the political economy run by the political elites. Cronyism and clientelism have become institutionalized as both the private and public sector go side by side in squandering natural resources and public funds through dodgy contracts in a clear violation of public trust.

Research on whether consociational power sharing agreements serve as a successful model in a multi-sectarian state or further exacerbates division has been deeply contested. Bassel Salloukh, An Associate Professor of Political Science at the Lebanese American University, has explored Lebanon’s model of governance in depth arguing that the economic hegemony exercised by the political elite through a sectarian corporate consociationalism is the main driver behind the resilience of the state.

Political leaderships have manipulated the system while establishing loyalties by offering social and economic safety nets. This base takes various shapes and forms in its endorsement of the status quo. In the wake of the October 17 revolution, it was divided into those who were reluctantly silent in the wake of the protests, those actively engaged in assaulting the protests and others who marched on the streets adjacent to the protests in a show of solidarity with the establishment.

Based on the demands of the protestors, the problem seems to be targeted at sectarianism, while the core problem lies within a corrupt political elite that has established corporate and economic ties to plunder the state’s funds. Given the lack of mechanisms for transparency and accountability, this political class has taken a sectarian guise for a total takeover of power.

The establishment of the sectarian political system stems from the conviction that seclusion breeds violence and marginalization breeds more violence. It was established as a framework that settles sectarian differences to allow people to rise above their religious insecurities to build a nation that serves as a melting pot for all sects. However, in its attempt to induce a shared national identity having put sectarian differences to rest, it was used to further stoke and inflame sectarian differences.

State-sanctioned abuse of power disguised by sectarianism

The political elite depleted the nation’s resources to serve personal and narrow sectarian interests.

The predicament with consociationalism does not lie within sectarianism, as its intended purpose was to guarantee an equitable share of power in an all-inclusive state for people whose ideology and culture are divided along sectarian lines. The political system was meant to make everyone feel part of the decision-making process, regardless of representation or power. However, it has failed to do so due to systematic and state-sanctioned abuse of power.

It is through this logic that Christian political leaders have been vocal in stating their opposition to endingthe sectarian political order, as it risks having a Muslim hegemony in the face of a decline in their numbers due to immigration, selling of land, more births amongst the Muslims etc.

In pre-war times, Christians ruled through what was dubbed as “Maronite Politics”. Muslims, at the time, called for an end to sectarian politics as a way of claiming some privileges. The Sunnis also called for it, despite the privileges they secured through the Taif agreement.. Following Hezbollah’s rise to power and the role it took on domestically and regionally, these calls were muted. Some of the most prominent Christian leaders argue that calls for an end to sectarianism is just a guise for a total takeover of the country under the progressively appealing banners of anti-sectarianism.

The core of the problem, however, does fall within the realm of corrupt politicians and not within the national pact that enshrined a power-sharing practice into Lebanon’s political life. Calls for regime change are part of a corrective pathway that only serve as a cosmetic measure that won’t necessarily solve the issues at stake. The complexity of Lebanese politics lies in governance and corruption rather than the sectarian allocation of power per se.

The political establishment profoundly abused the system that gave them leeway in terms of privileges as leaders of sects to maintain an iron fist through political impunity and economic hegemony. The system that called for their inclusion has been manipulated by corporate contracts and dodgy deals with the private sector, turning political figures into immune businessmen that siphon off the nation’s funds and run patronage networks parallel to the state.

Sectarian politics have taken over the country’s resources, whether in development projects, construction, telecommunications, or electricity.. The political elite depleted the nation’s resources to serve personal and narrow sectarian interests. An abuse of power through enforcing sectarian ties and sectarian divisions has kept them in power for the longest time by means of a totalitarian ideology that clings on to power and even passes it on.

As for governance, Lebanon’s cabinets have proven to be dysfunctional and ineffective while trying to incorporate contradictory agendas amongst ministers that are ideologically at odds with one another in the name of a “unity government.” It lacks the unity in every sense of the word, having no shared vision and no coherent agenda as conditions for policy-making.

The resignation of a third of the cabinet members plus one can bring down the government, similar to what happened with Hariri in the wake of the cabinet’s refusal to pass a key resolution over the UN tribunal investigating the assassination of former prime minister Rafic Hariri. The parliament failed 44 times to elect a new president because the quorum was not met. MPs derailed the political process by abstaining from attending the parliament sessions to get their candidate to the presidential office. The office of presidency remained vacant for two and a half years until one coalition was able to force its candidate on the rest.

The current political system has been voted down. Historical revisionism is needed at this stage, one laying out a corrective plan of action that retains the specificities of the Taif agreement while tackling the flaws of consensual politics. Above all, it must present a feasible course of action that roots out corruption.