“We call on the Lebanese public opinion, on our parliamentarians, and on all political parties and political and spiritual leaders. We request that they be informed that the Bisri Dam project is a ticking atomic bomb,” said Dr. Tony Nemer, assistant professor of Geology at the American University of Beirut, at a press conference on June 27. “Lebanon cannot handle the danger of its presence.”

The National Campaign to Protect Bisri Valley and the Lebanese Environment Movement organized the press conference in response to the Council for Development and Reconstruction’s (CDR) allegations about the Bisri Dam project, which they believe poses several environmental, resource mismanagement, and public safety hazards.

Plans for the project began in the 1950s and developed over time. Along with the Qaraoun Dam, the Bisri Dam was designed to bring water into Beirut. While the Qaroun Dam was implemented, the Bisri Dam project was shelved until funding was approved by the World Bank in 2015. Of its 1.2-billion-dollar cost, 600 million is loaned from the World Bank. According to the CDR, the dam is set to provide water for 1.6 million people living in Greater Beirut and Mount Lebanon, to cover 6 million square meters of land, and to contain 125 million cubic meters of water.

Despite the benefits that the CDR is promising from the Bisri Dam project, environmental activists are not convinced.

The Case Against The Bisri Dam Project, Explained By An Activist

The National Campaign to Protect Bisri Valley, which kicked off in 2017 as a Facebook page by independent activist Roland Nassour, grew out of an increasing opposition to big dam projects because of the ecological harm and safety hazards they pose.

“Our environmental activism and our opposition to dams was new, especially with the Lebanese history of believing that dams are good and that not a drop of water should go to the sea,” Nassour, a graduate student at the American University of Beirut, told Beirut Today. “This paradigm is rooted in the minds of the Lebanese people and, to change it, we need time.”

According to Nassour, projects like the Janneh Dam, Balaa Dam, and Msaylha Dam set a precedent for the Bisri project opposition, in addition to other dam projects facing complications because of the inability of the land to accommodate big water reservoirs.

The Bisri Valley is categorized as a protected regional environmental park by the National Physical Master Plan of the Lebanese Territory, as well as a natural site to be protected by the Ministry of Environment in 1998. According to activists, around 150,000 woodland trees will be cut for the dam. The “environmental genocide” could even take up to 500,000 trees. It is the only valley in Mount Lebanon to have an expansive agricultural plane, as well as over 50 archeological sites that will be destroyed by the project.

Around 570 hectares of land will be expropriated and inundated, including 150 hectares of agricultural land, 82 hectares of pine woodland, and 131 hectares of natural vegetation. The coalition campaigning against the dam reports that around 150,000 woodland trees will be cut and that this number might go up to 500,000, besides agricultural orchards, labeling it an environmental genocide.

Launched as a way to share the importance of the Bisri Valley as a natural touristic site, the online campaign would bring together Bisri locals and environmental experts to shed light on the alarming consequences of the dam as more people heard about the project.

Aside from the environmental, water mismanagement, and public safety concerns, questions regarding the need for such a dam took center stage in the discussion. Experts from the Bisri campaign also publicized the presence of a highly-active earthquake fault under the Bisri Dam site.

CDR Doesn’t Back Its Claims With Science, But With World Bank Propaganda

CDR has, for the first time, set up a Facebook page dedicated to posting information on the Bisri Dam that counters the claims made by activists. The World Bank has also played its part in advertising the project on its own website through a series of articles and documents.

“They pay money for this page, they pay the money of Lebanese citizens to sponsor advertisements. The page is filled with propaganda,” said Nassour. “The council points back to the World Bank instead of arguing with scientific data, hiding under the fact that international experts have approved funding when in reality the World Bank is not a scientific resource.”

As more individuals rallied against the project, the Parliamentarian Committee for Public Works requested on April 4 that the CDR release the Bisri Dam studies dating back to 2014. The CDR released the requested documents 70 days after the request –or on June 14– along with a statement by Dr. Mustafa Erdik, Seismology lead expert on the project, and Dr. Ata Elias, professor of Geophysics and Geology.

In its recent press conference, the National Campaign to Protect Bisri Valley and the Lebanese Environment Movement tackled the CDR’s allegations using previous studies released by the council itself.

The Myth of Water Scarcity To Justify The Bisri Dam

The council often refers to the 2012 National Water Sector Strategy by the Ministry of Energy and Water to justify the need for the Bisri Dam on the basis of water scarcity in Lebanon. But the ministry has not monitored water from precipitation, springs, groundwater basins, and wells since the late 1960s, as outlined in studies from the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) and the CDR itself. The government also does not have documentation on unauthorized springs controlled by mafia groups that sell water to citizens.

Around 70 percent of Beirut’s water is provided from the Jeita Spring, but 40 percent of that water goes to waste before even reaching the capital because of poor maintenance and a rotten waterpipe network that suffers from uncontrolled leakage. If Lebanon suffers from a water scarcity problem, it’s not because the country lacks in resources. It’s because authority figures deplete and mismanage them.

The little amount of statistics, and particularly statistics from local researchers, also points back to a severe mismanagement problem in Lebanon’s water sector. Building more dams, without exploring their impact on the environment and whether they are suitable for the lands they are being built on, is wasteful. Just look at the Brisa Dam, which remains largely empty despite costing millions of dollars.

“How are they coming up with these numbers without having the statistics? They decide on the project and then stick the numbers to it, not the other way around,” said Nassour.

Another testament to the government’s failing dam campaign is this: better alternatives exist. The Strategic Environmental Assessment for the New Water Sector in Lebanon proposed submarine springs as an important water option that could yield around 650 cubic meters of freshwater, or six times the capacity of the Bisri Dam.

A “highly active fault and the source of earthquakes” runs under Bisri Valley

The CDR released 36 reports on the Bisri Valley under the request of the Committee of Public Works, amounting to a total of 8,095 pages. However, as pointed out by Dr. Tony Nemer, 56 additional reports on the Bisri Valley were missing.

The CDR adamantly disqualified the presence of an active fault line under the Bisri Valley by referring to studies from scientists who work on its behalf, despite the presence of numerous other studies from the council which prove otherwise. Out of the 36 released reports, only two reports offer a counter-explanation regarding the seismic nature of the valley, both of which have been conducted by CDR representatives.

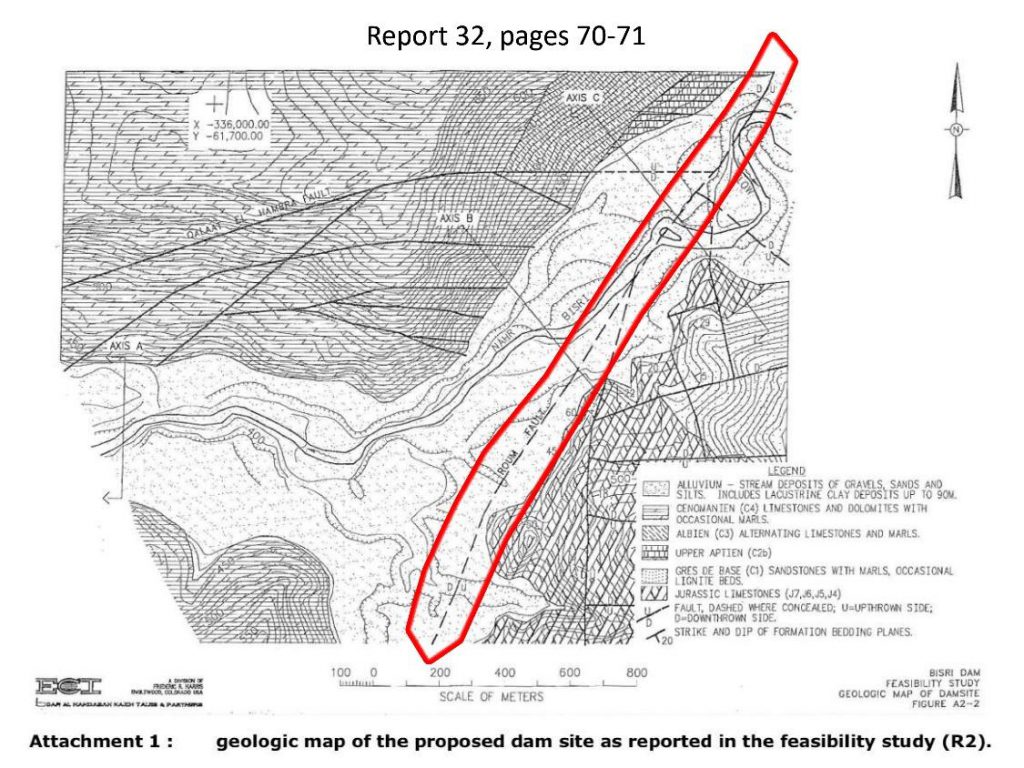

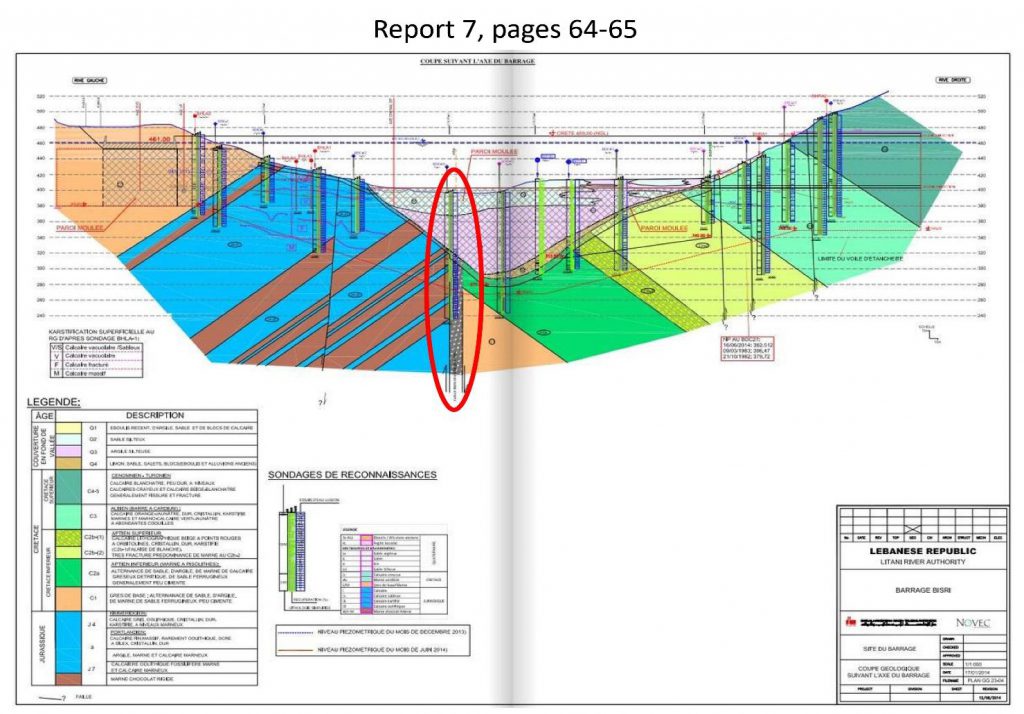

A report on the environmental and social impact assessment of the Greater Beirut water supply augmentation project by Dar Al-Handasah (Shair and Partners) outlines the seismicity of the Bisri Valley. The August 2014 report lists taking productive land, risking historic and cultural remains, and high seismic risk as some of the main disadvantages of the project. The report also describes the Roum Fault, which passes under the Bisri Valley, as a “highly active fault and the source of earthquakes,” concluding that the study of the dam “requires a detailed risk identification and assessment” which the CDR has yet to provide.

Another March 2016 report from Professor Antonio Gens of the Technical University of Catalonia also states that the “Bisri Dam is sited in a highly seismic zone.”

Despite assurances from the CDR that the Roum Fault (sometimes referred to as the Bisri Fault) is dormant and that no extension of this fault passes pass under the Bisri Dam, figures from the Moroccan engineering consulting company NOVEC and American engineering firm ECI (see below, Roum Fault circled in red) were used in 15 out of the 36 released reports to demonstrate the seismic danger that the dam poses.

Historically, the Roum Fault has been the cause of several major earthquakes. Two earthquakes with a magnitude of 8.3 were recorded in 1201 and 1759, according to the previously mentioned Dar Al-Handasah report. More recently, a 6.0 magnitude earthquake occurred four kilometers east of the proposed dam site in 1956, causing 136 deaths and destroying 6,000 homes. The closest surface expression of the Roum Fault is about two kilometers southwest of the dam site.

In their statement, the CDR also eliminated the possibility of Reservoir Triggered Seismicity (RTS), which refers to earthquakes triggered from stress exerted by water reservoirs on earthquake faults.

The council referred to the ICOLD’s (International Commission on Large Dams) Bulletin on Reservoirs and Seismicity to conclude that RTS appears to occur on dams which are higher than 100 meters and that contain over a billion cubic meters of water. CDR claims that the Bisri Dam, which will stand at 60 meters and contain 125 million cubic meters of water, cannot induce RTS.

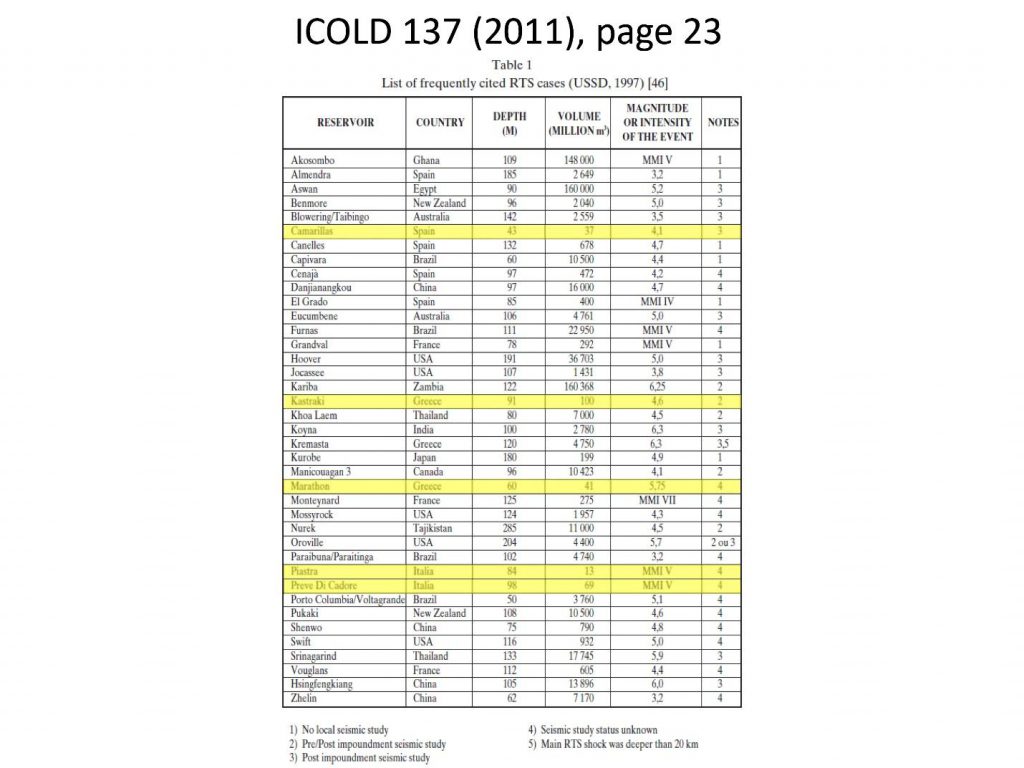

However, Nemer referred to cases of RTS relating to reservoirs which did not meet the requirements outlined in the statement and yet have caused notable earthquakes, dispelling the council’s claims.

According to Nassour, the campaign’s strongest suit is its ability to provide facts and scientific evidence despite the misleading and contradictory information provided by government bodies.

“All political parties present in the government benefit from this project. Therefore, there is a consensus among the political class around the Bisri Dam because this is one of the biggest projects in government right now. There is a huge benefit, considering that the country is run by contractors,” Nassour told Beirut Today.

The dam project is indeed costly: $320 million has been allocated for the dam’s construction, $220 million for contractors’ costs, $66 million for contingencies, $10 million for engineering, $20 million for the construction of a transmission line, $15 million for the construction of a hydropower plant, and $150 million for the expropriation of properties around the project. Another $4 million has also been set for overseeing and managing the project. These exorbitant costs, when considering the lack of proper infrastructure and a decent monitoring process, leave room for an illegitimate private gain of authorities that is similar to the case of incinerators in Lebanon.

Despite strong support from key political figures and attacks orchestrated against activists working on the project, Nassour is hopeful that the public is increasingly becoming more skeptical. Dialogue with the World Bank has not been effective, as it continues to fund and promote the project.

The campaign continues to have a strong presence both online and offline, monitoring the information being circulated around the project and steering the discussion by providing factual information supported by scientific evidence. While the campaign’s future remains uncertain, the public’s role in pressuring respective political leaders remains as imperative as ever.