“They were called the Smurfs, and we were all around the same age. Some were even younger than 20,” said renowned war photographer George Azar, recalling his coverage of the Lebanese Civil War that waged between 1975 and 1990.

Twenty nine years after the end of the civil war, such images still trigger questions and doubts: Who were the Smurfs? What area were they staying in? What was the use of the axe tied to the man’s back? No answer will be found beyond personal recollections.

A quick look around Azar’s office at the American University of Beirut, where he teaches as a photojournalist in residency, unravels years of untold humanist stories from the war. Although inanimate, these images reveal a history waiting to be told, a history apart from the political actions and reactions, and a history living through the lens of the photographer. Each image was a product of what Azar witnessed, and his perception of society and the world.

Discussions about the civil war often take a melancholic turn, especially among the generations that came after it. “There is something about hardship that makes life more vivid,” shared Azar.

Events seem to be more abundant and present when one looks back at a compressed historical timeline. There is something alluring in the way parents retell stories they’ve lived, or the book selections that young ones choose to read as a means to inform themselves about their own country’s fragmented history, ironically, one not covered by history books. The civil war era is symbolised by a nonexistent multi-faceted book, with hundreds of interchangeable covers and unresolved narratives. More concretely, there is not one agreed upon truth that could summarise the events for future generations to learn about, making way to untruthful or one-sided accounts.

“One never knew what was going on,” explained Azar, “Sources were politicised, and this has a negative impact on society.”

“Then We Realised That We Were The News”

Azar, who is Lebanese American, was pursuing his education in the United States at the time the war started. Receiving news back then was restricted to print media, television or on the spot radio transmitters. When Azar arrived to Lebanon as a front line reporter, he was getting on the ground news by listening to the radio. He added on this experience by saying “we thought we were listening to news, then we realised that we were the news.”

The difficulty of receiving reliable and accurate news during the civil war and the fact that listeners chose the perspective they wanted to hear by tuning in to a certain radio wave were triggering points for Azar, who chose to come back to Lebanon. “I just wanted to tell the truth.”

The diverse communities born out the war are consequently placed on a precarious pedestal, each fighting for their version of the story to win, generating more profound divisions. While this statement was said to describe the situation almost 30 years ago, Lebanon today does not shy away from the politicisation of the news. It remains a survival of the fittest.

As a result of this history blackout, or rather self-inflicted amnesia, some citizens resort to photography and art as a means to communicate with whoever wants to listen.

“Photography is a literal representation of reality, whatever fits in the camera frame,” said the photojournalist. “There is a reason your passport has a photograph of you and not a written description or a poem.”

Evidently, cameras are truth generators that store evidence, which explains why some people feel uneasy with their presence, especially in controversial moments. Media outlets resort to photography as a means to shock readers and offer a real life representation of the assessed situation. Rarely do readers wonder about the situation behind the camera lens.

It is no parent’s wish to see their children covering war stories. Media used to replicate experiences lived by journalists are far from relatable to the general public, and Azar’s story, which is one of many, is a testament to that.

Captured by Israel, Released Into A Civil War Battlefield

During the early days of the war, Azar was living in Beirut and covering segments as part of a Western magazine. It was then when an estimate of 80,000 Israeli soldiers infiltrated the lands. Azar and other journalists were on their way to cover the event but when the taxi abandoned them at Jieh, the group sought refuge with a small group of Palestinians fighters.

“We asked them to direct us back to Beirut, but we were told that it’s too late. I mean, we were ten in total, versus thousands of fighters,” said Azar, “So they just resorted to drinking tea and smoking cigarettes waiting for their fate to be determined. I was not ready.”

It wasn’t long until the tanks arrived and wiped the area, uncovering its soil and debris. Azar surrendered with the help of a makeshift peace flag: a white jacket and a wooden stick. But the story didn’t end there.

Three days after his capture, Azar was released from the Israeli base and told to walk from the front line back to Beirut, leaving his fate to the Lebanese and Palestinian fighters. While it is a given that Azar’s fate was survival, his pictures weren’t as fortunate.

Honesty, integrity and accuracy within the journalist field disintegrated during the civil war. To find truthful, fair and backed reporting was as rare and unachievable as freedom. “The magazine only published the pictures featuring Lebanese and Palestinian soldiers shooting towards the Israelis, and not the other way around, or both,” recalled Azar. “So I just quit.”

Photography to Rebuild and Reconstruct

Photography is a universal language that speaks wonders. A family picture taken decades ago initiates a mixture of happiness and a longing for a period of time lived, but never comparably returned. They are a form of memorabilia that anyone resorts to, to freeze a millisecond, duplicate it and preserve it. One can then grasp the importance of conserving history, facts and the proof of a life. In an ever so destructive phase, these photos were used to find missing family members, to locate a destroyed house, or to provide survivors with a constant reminder of hope for and from loved ones. These images were also the first used to rebuild memories and reconstruct what was deconstructed during the war.

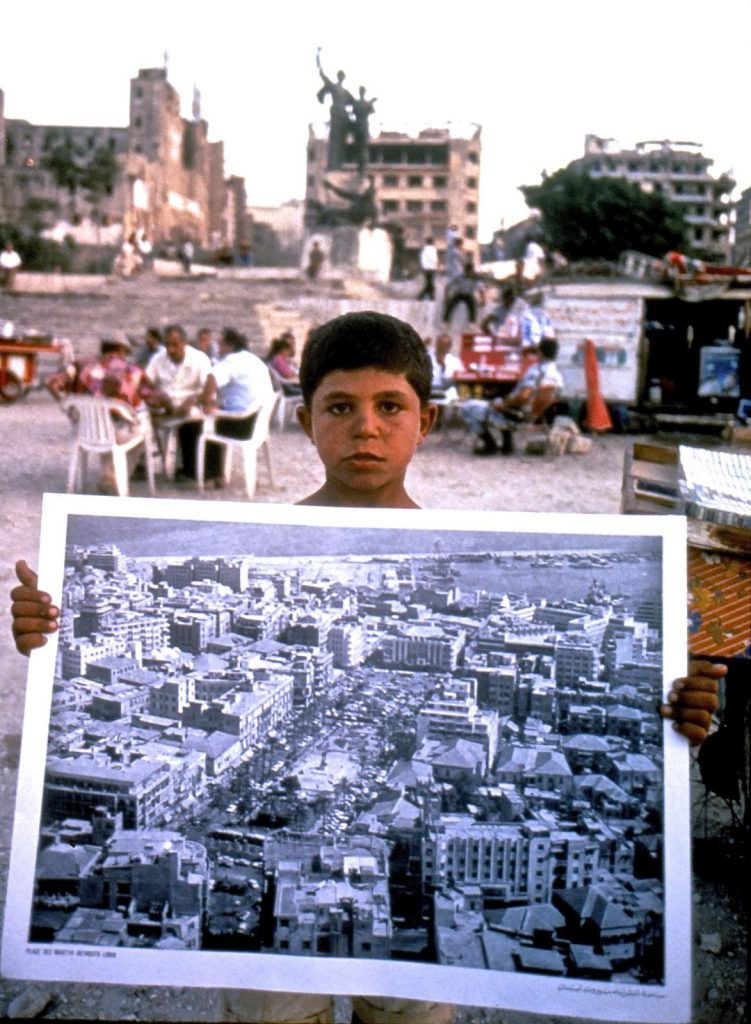

“This picture was taken soon after the war ended, and this little boy was selling pictures of what Downtown used to look like before the war,” explained Azar while looking at one of the hung pictures on his office walls. “It was so peaceful, people were playing cards, drinking coffee and chatting in a destroyed Martyrs Square. As if nothing had happened.”

A closer look at the boy’s eyes gives way to sadness and uncertainty, but life moved on, latching onto unpredictability and an ambiguous storyline.