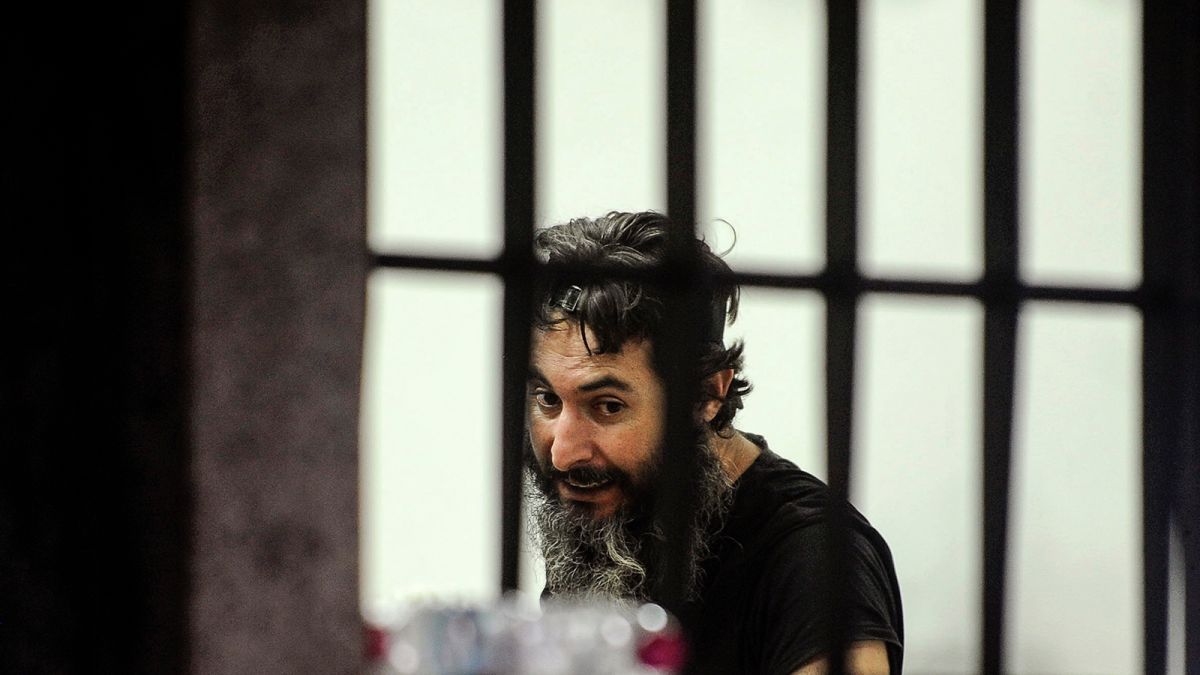

Bassem Sheikh Hussein stormed Hamra’s Federal Bank on August 1. He was armed with a gun and tank of gasoline, and held around 7 hostages while demanding the bank return his deposit of $209,000 to pay for his father’s $50,000 treatment. Later that day, he released the hostages and left the bank with $35,000 from his own deposit.

This event sparked a debate throughout the country: was this ethical?

Many deemed the man a hero, while others criticized his behavior. A month later, five similar hostage situations would occur across the country’s banks, raising the same question once again.

The Banality of Evil

The events over the last two months have reminded me to an extent of an aspect of “the Banality of Evil”, a concept coined by German Philosopher Hannah Arendt.

Arendt published her controversial book “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” in 1963, which talks about Nazi Otto Adolf Eichmann, who was on trial for his role in transporting Jews to concentration camps during the Final Solution.

Arendt describes that “the deeds were monstrous, but the doer … was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous.”

In December 2021, the Central Bank of Lebanon implemented a new withdrawal system where depositors are only allowed to withdraw $3,000 per month at the rate of 8,000LL – even though the dollar rate has reached 38,000LL.

Due to the country’s crippling economy, the gradual dollarisation of services, and withdrawal limits, citizens have decided to take matters into their own hands.

In the case of hostage situations, the Banality of Evil comes into play since these offenders are committing “evil”, even though they themselves may not be inherently evil people with bad intentions.

They may simply be victims of a failed state and a corrupt government, and are only retrieving what is originally theirs.

This is not to say that I personally condemn the actions of these people. After all, there are two sides to the same coin. I believe that in these situations one cannot be a hundred percent with or against these occurrences.

On the one hand, these individuals are restricted access to their own money during a time when Lebanon’s economy is deteriorating on a daily basis. For the past three years, Lebanon has experienced what the World Bank described as one of the worst economic crises in the last 150 years. Since 2019, the Lebanese Lira has lost over 80% of its value, resulting in price hyperinflation and approximately 80% of citizens living below the poverty line.

The money they need in order to provide for their families, fund their medical treatments, and survive amidst the country’s crippling state. In their eyes, desperate times called for desperate measures – and in many ways, these actions can be justified when looking towards the greater context.

Looking at the other side of the coin, these holdups are potentially leaving hostages and their families traumatized since most of the offenders were armed and, in some cases, threatening to light themselves on fire with gasoline.

Most of the offenders managed to receive a partial payment from their own deposits upon releasing their hostages.

This is somewhat problematic since it is normalizing bank holdups to obtain your own money, meaning these situations may continue to occur in the future. Although no injuries or casualties have resulted from the six holdups, there is always a possibility that the next person may not be so merciful.

In these times of trouble, our moral compass becomes distorted and our survival instincts tend to kick in. Therefore I leave it up to you to decide: is this ethical?