The UDHR (Universal Declaration of Human Rights) has often been criticized as a document that enshrines Western values, mores, and norms. Critics often argue that since these values have been documented by the West, they then reflect Western interests and are therefore used as a weapon of cultural hegemony. Others argue that human rights emanate from a European Judeo-Christian tradition and so, cannot be applied to other societies that do not emulate the conditions and values of “Western societies.”

These claims are highly problematic as they exclude a large bloc of the world that opposes Western globalization, exempting them from the ethical obligation to abide by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The UDHR document must not only be abided by, but also promoted as fundamental to all international moral frameworks.

Upfront, claiming that the UDHR is a Western document would imply that Western states unanimously agree on the content of the document, while non-Western states would disagree.

The reality is that not all Western countries ratified the UDHR during the first round of ratifications. In fact, Canada, a state that Human Rights Watch says enjoys a global reputation as a defender of human rights, had abstained from signing the document during the first round of ratifications at the General Assembly in 1948.

The previous argument implies that non-Western states would tend to disagree with the document. But most Muslim-majority countries that were then members of the United Nations signed the Declaration in 1948, including Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, and Syria, which has an overwhelmingly Muslim population but an officially secular government that also voted in favor.

A leading counterargument is the example of Lebanon, a state renowned for its sectarian division and powerful religious authority, both Christian and Muslim. Not only did Lebanon vote for the Declaration in 1948, but technically took part in the drafting of the UDHR. That is because Charles Malik, a Lebanese political figure, was a leading member of the drafting committee.

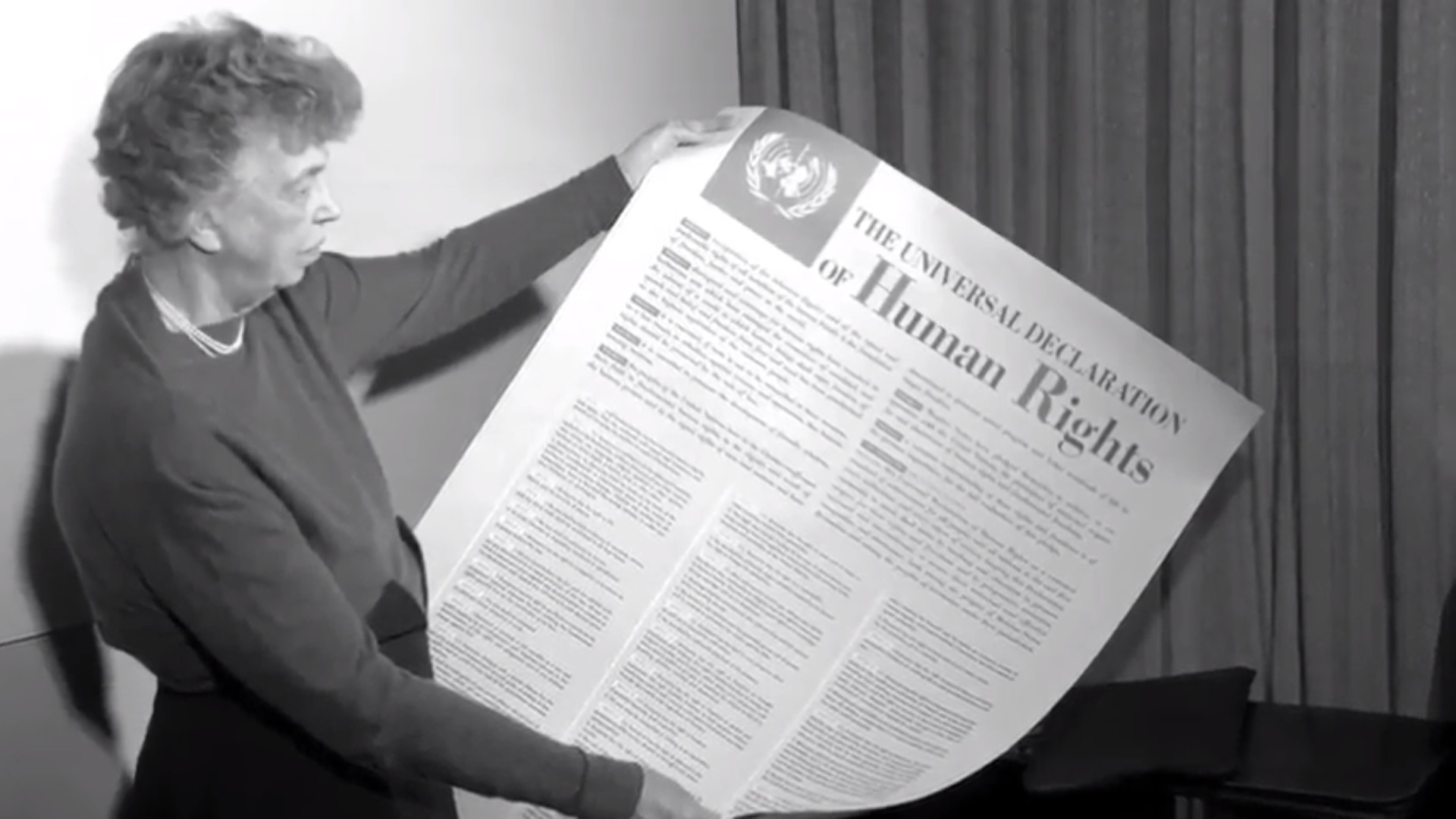

The example of Charles Malik also counters the criticism the UDHR is facing, given that members of the drafting committee were not exclusively Western or Christian. Certainly, there were Western figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt from the United States and John Peters Humphry from Canada, but members of the drafting committee had come from all around the world—including the Middle East, Far East, and South-East Asia. And yes, the repetition of the word “East” is part of the argument.

How could the document then be considered Western if it were drafted by members from all around the world? Surely if the articles had contradicted moral values existing in other parts of the world, there would have been objections to the implementation of these articles. The diversity of the drafting members in gender, race, religion, and ethnicity served as a balance to reach common ground on the fundamentals of what human rights are.

You would expect Western countries to abide by the text, in the opinion of the critics that enshrine the UDHR as a Western or Christian document, but that is simply not the case. In 2014, then-President of the United States, Barack Obama, admitted that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had “tortured some folks” in an attempt to retrieve key information about the terrorist organization Al-Qaeda.

Any act of torture explicitly violates Article 15 of the UDHR that states that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. In particular, no one shall be subjected without his or her free consent to medical or scientific experimentation.”

I will not deny that the UDHR document contradicts certain interpretations of religious beliefs that are non-Western or non-Christian, like the Islamic Interpretation of the right to change your religion. In fact, that is the main reason the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) had abstained from signing the document in the first place. Powerful Islamic scholars in the Kingdom claimed that freedom to change religion is an act of apostasy. That opinion contradicts Article 18 of the UDHR that gives the right to our own beliefs, to have a religion, have no religion, or to change it.

However, other scholars share the opinion that everyone is free to act upon their religion on their own. The main counterargument used is the Qur’anic teaching that there is “no compulsion in religion” and “to you your religion, to me mine” (Qur’an, 109:1-6) and the Prophet Mohammed famously declared freedom for Muslims, Jews, and pagans in the constitution of Medina in 620 AD.

Nonetheless, different interpretations of religious texts within different societies are not exclusive to Non-Christian and Non-Western societies. The Westboro Baptist Church has successfully contradicted most of the articles within the UDHR. Starting with the first article that states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

In response to the latter part of this article, the Westboro Baptist Church interprets the infamous biblical quote “Love Thy Neighbor,” which involves “rebuking” our neighbor, as justifying the use of various forms of hate speech. This includes, but is not limited to, “God hates Fags.”

This leads me to say; if a religious interpretation finds its way into law, it does not make it any more legitimate than the interpretation that doesn’t. There will always be an opinion that will not align with others.

I find it highly oblivious to consider the UDHR as a solely Christian or Western document. There are Christian and Western actors that do not abide by the UDHR, much like there are Eastern and non-Christian actors that do. The rights that are protected by the UDHR are not exclusive to Western or Christian societies, they protect everyone and that’s what makes the text Universal.