The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) has released a new report demonstrating how “Lebanon has experienced a significant surge of collective mobilization nationwide amid worsening economic conditions” since the beginning of 2021.

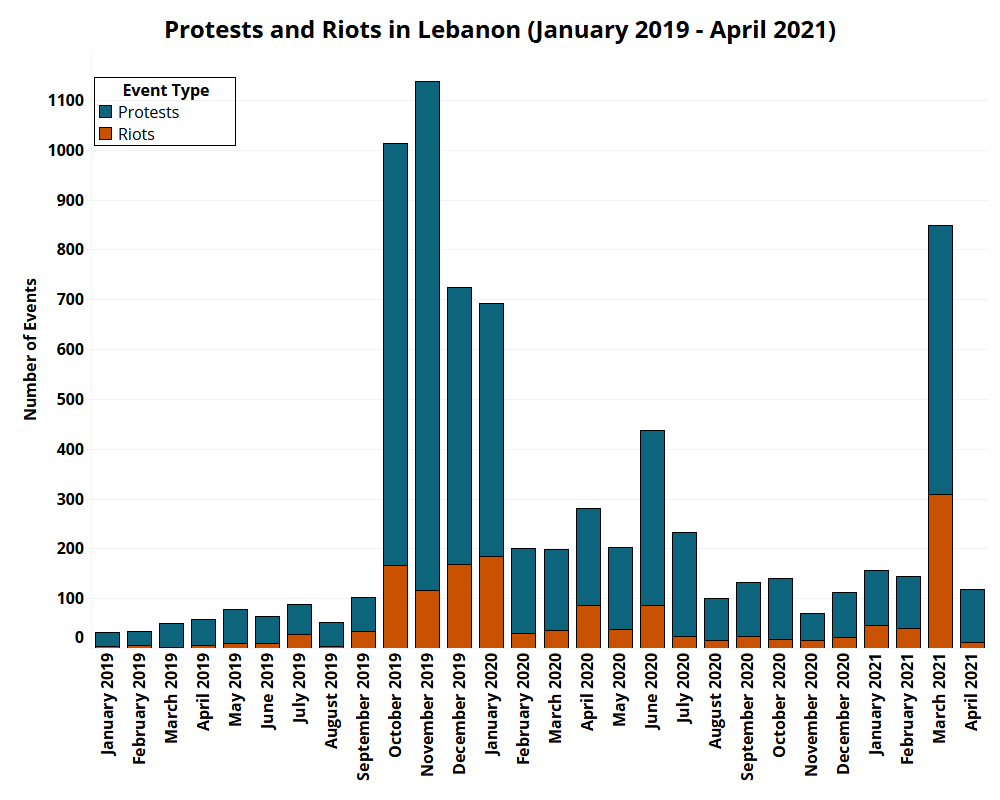

In October, 2019, nationwide demonstrations were sparked in protest of deteriorating living conditions and widespread corruption across political institutions. Demonstrations were an active part of daily life in Lebanon, up until the start of the coronavirus pandemic in March, 2020.

Afterwards, demonstrations became less frequent and more sporadic, the most significant of which took place following the August 4 blast. The initial conditions which drove people to the streets have only worsened since then.

According to ACLED, “the number of demonstrations recorded in March 2021 was the highest since the onset of the popular uprising in October-November 2019. Unlike 2019, however, demonstrations have turned increasingly violent.”

The past two years

October 17, 2019 is largely marked as the day the Lebanese revolution started. On this day, the Lebanese lira began to depreciate, reaching LBP 1,650 against the dollar on parallel markets in contrast to its pegged rate of LBP 1,550.

Currently, the lira is trading at around LBP 12,800 for every one dollar. Subsidized goods, such as meat, toiletries and more are quickly disappearing as the country’s foreign currency reserves deplete.

As per the World Bank, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth contracted by 20.3 percent in 2020. Inflation “reached triple digit while the exchange rate kept losing value.” Around 40 percent of the country is unemployed, and over half are living under the poverty line.

For those privileged and capable, legal emigration offers an alternative to bearing the crisis. For those who are not, migrating to other countries often assumes dangerous forms –such as dangerous trips through packed “death boats.”

Watch also: Being “already dead on land” shrouds the dangers of illegal immigration

A recovery plan in cooperation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was in the works this time last year, but is currently on hold in light of political deadlock. Prime Minister-designate Saad el Hariri was appointed in October 2020 to form a new government that could help rescue the country from economic collapse.

Hariri had previously stepped down in October 2019 after protestors demanded his resignation for failing to improve the country’s situation in recent years and for being a part of the corrupt political class. Since his reappointment, he has failed to create a government in agreement with President Aoun, as the two are regularly at odds in private and public.

Alongside these economic and political crises, Lebanon is also just now curbing a massive outbreak of COVID-19 that has paralyzed its healthcare system and overworked its healthcare professionals since the start of the year.

The shifting nature of protests

Lebanon’s crises are far too many to quantify, but they are the key reason demonstrations have escalated this year. As per this report, ACLED documented that only 16 percent of total demonstrations were violent in 2019, in comparison to a third of all demonstrations in 2021.

Demonstrations took place widely across the country, including Beirut, Baabda, Aley, Zahle, Tripoli and Saida, “highlighting how political disorder has been widespread across the country.”

When the lira hit an all-time low in March, frustration and anger grew amongst members of the population. Videos showing fights over subsidized foods became more popular on social media.

On Sunday, May 18, a man was reportedly shot at a gas station over a scuffle. Gas stations across the country had become overcrowded in the past few days as citizens rushed to fill up gas before subsidies were removed, and also due to a fear of an imminent gas shortage.

Between October 2019 and March 2021, the Samir Kassir Eyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom documented assaults on nearly 200 media workers by security forces and non-state groups. In February, writer and renowned Hezboallah critic Lokman Slim was murdered by unidentified gunmen. Many now consider Lebanon’s freedom of speech to be under severe threat.

Not only so, but “personal disputes and feuds over drug smuggling are also driving clan-related violence.” In 2020, clan-related violent events increased “almost fourfold” in comparison to 2019, and the trend still continues in 2021. At least 25 people were reportedly killed in clan-related violence across the country.

These are not isolated incidents, nor should they be perceived as so. All these events are social consequences of the ongoing events in Lebanon, which have touched upon every area of life with no exceptions. A recent video by Megaphone News directly links the increase in depression and anxiety amongst individuals in Lebanon to the political, economic and health crises we are collectively experiencing.

ACLED says the recent turmoil, in comparison to the protests in early October 2019, is significantly more violent, “a reflection of both increasing popular frustration with the country’s political elite and competition among political groups for increasingly scarce resources.”

Should the situation remain stagnant with no end in sight, “heightened competition and popular frustration are likely to persist,” with the possibility of escalation as the May 2022 general election looms before us.