It has been over six months since the deadly Beirut blast decimated swathes of the city and killed around 200 people. The blast was largely a result of the ignition of a large amount of ammonium nitrate fertiliser, stored at the port since the year 2013.

How the ammonium nitrate came to the Beirut port

Ammonium nitrate is commonly used as a fertiliser, but when combined with fuel oils, it can then be utilised as an explosive. It is largely safe when stored properly, but it then begins to decay if stored away for too long.

The large amount of ammonium nitrate arrived on board the Moldovan-flagged cargo ship MV Rhosus en route to Mozambique. According to official reports, the Rhosus was inspected, banned from leaving, “abandoned by its owners”, and its cargo transferred to Hangar 12 following a court order.

The initial amount of ammonium nitrate stored in Hangar 12 is reported to be around 2,750 tonnes. However, an FBI investigation revealed in late December that the amount that exploded only amounts to 500 tonnes. The whereabouts of the remaining explosive materials remains unknown, although new discoveries are constantly being made at the port.

The owners of the ammonium nitrate

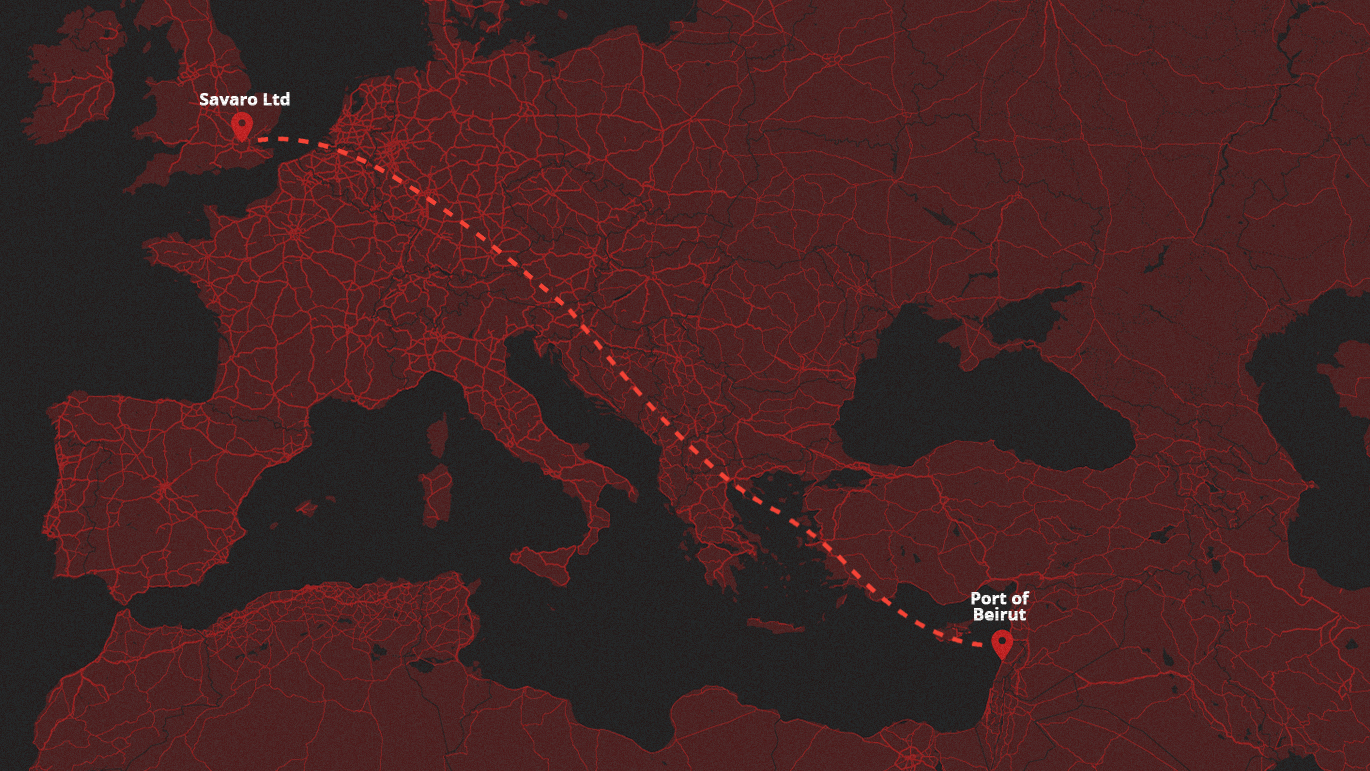

In 2013, British firm Savaro Limited purchased the ammonium nitrate from Georgian chemicals factory Rustavi Azot. The explosive materials were to be sent to a Mozambican factory, Fabrica de Explosivos de Mozambique (FEM).

Savaro is registered as a chemical trading company in the UK, but is likened to a shell company. It does not have many real employees, very little business proceedings, and has so far refused to disclose its beneficial owners according to a report by Reuters.

An ultimate beneficial owner, or UBO, is defined as “someone who receives the benefits of an entity’s transactions, typically owning a minimum of 25% of its capital” as stated by Reuters.

The company’s ties to the Beirut blast has sparked outrage amongst British lawmakers and ministers, who have demanded a thorough investigation into the company’s proceedings.

In an interview with Reuters, Marina Psyllou, who is listed as the company’s sole director and owner, denied having any links to the explosion. She also told the news agency that she acts as an agent on behalf of Savaro’s true owner, whose identity she cannot disclose.

“As far as we know the company in question, ever since its registration it remains dormant without any trading or other activity or keeping any bank accounts as the project for which it was incorporated was never realised,” she told Reuters.

Psyllou is registered as the officer for at least 157 companies, some in the UK and others in Panama, which is said to be a “haven for shell companies” according to a report by Al Jazeera. Additionally, Savaro’s legally registered London address is being used by several other companies.

Psyllou had filed a request to dissolve Savaro, an alarming move considering the worldwide attention Savaro is receiving in its link to the Beirut blast.

Melhem Khalaf, head of the Beirut Bar Association, sent a letter to British MP Margaret Hodge asking her to prevent the liquidation which “would permit an indicted entity to evade justice.”

Following his letter, the United Kingdom’s registrar of companies issued an official decision to stop Savaro’s liquidation process.

Three Syrian Businessmen linked to Savaro

An Al-Jazeera report has linked three Syrian businessmen with close ties to the Syrian regime to Savaro. The businessmen were identified as George Haswani and brothers Imad and Mudalal Khuri.

According to the report, “companies formerly directed by Haswani and Imad Khuri have the same stated addresses as Savaro Limited.”

Haswani denied any knowledge of or ties to Savaro. According to his interview, he hired Cypriot agency Interstatus to register his company. Interstatus is the same agency that registered Savaro, and Haswani says that the agent coincidentally shifted the registered address to the same one.

All three men have been sanctioned by the United States “for allegedly aiding and providing services to the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.”

The linkage has raised several questions as to whether Savaro is another player in an effective laundering scheme that brought the ammonium nitrate onto Beirut’s port.

Seeing as the explosives docked in Lebanon around the same time that Syria’s war had just begun, this also raises questions about whether the explosives had docked in Lebanon in order to be transported later on to Syria.

The Beirut port investigation

Six months onwards, and the local investigation headed by Judge Fadia Sawwan has yet to yield any effective results.

Around 30 people, mostly mid or low-level port, security, and customs officials, have been arrested since the blast took place on August 4. No charges or evidence has been presented against them, according to Human Rights Watch.

In December 2020, Sawwan filed charges against caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab and three former ministers under the pretence of negligence resulting in the death of 200 people.

All four governmental officials did not appear for questioning, denying the charges against them and going as far as accusing the judge of violating the constitution by bypassing parliament’s authority to try ministers.

Sawwan’s decision came under heavy criticism from parliamentary officials and political parties, with caretaker Interior Minister Mohammad Fahmi saying he would not call on security forces to arrest the charged ministers even if judiciary warrants were issued.

On February 11, former army chief Jean Kahwagi appeared before Sawwan for a lengthy hearing that reportedly lasted an hour and a half. Other officials tied to the blast have also been summoned for various hearings.