We dream of home being where we came from, but the reality is that too often, that place does not exist.

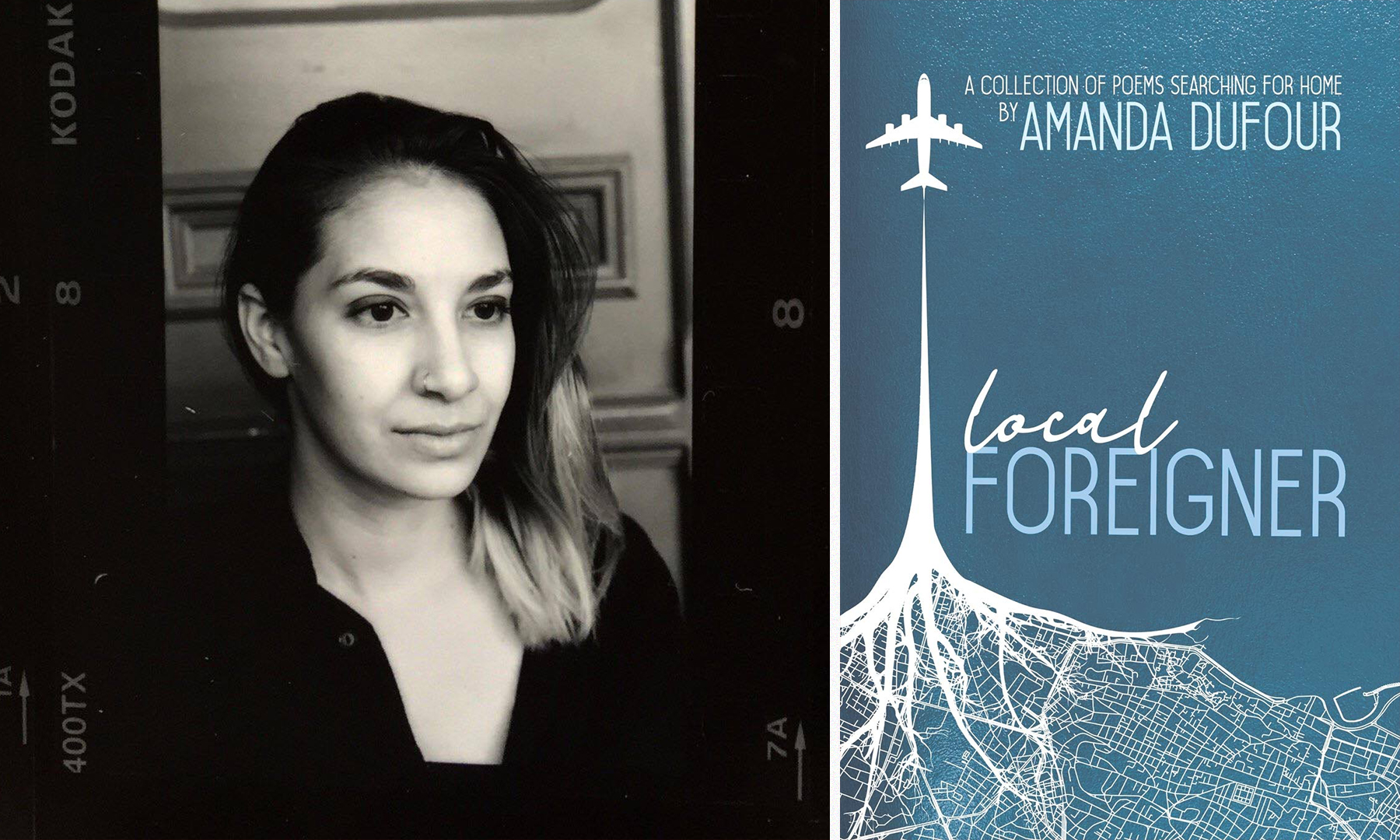

Amanda Dufour, “Local Foreigner”

Amanda Dufour, author of the newly released poetry anthology “Local Foreigner,” sits inside my computer screen late Wednesday afternoon. The light from her London apartment shines two hours brighter while she recounts her journey grappling with questions of belonging.

As a half-Swiss, half-Lebanese girl, Dufour’s childhood was laced with the frustrations of being suspended between strings of certain identities. Even though she has spent most of her youth growing up in Lebanon, creating deep connections on these crooked grounds, she is refused concrete forms of attachment to it because her mother cannot pass her Lebanese nationality. The weight of her father’s “foreignness” on legal documents creeps into the intricacies of Dufour’s interactions and how others perceive her: as “ajnabiyye.”

“I’ve always had a need to express myself creatively without actually speaking,” Dufour says about her multiple artistic careers. As a freelance dancer, she finds solace in physical expression, while writing allows her to put her thoughts onto impartial pages without having to speak them. Her writing has been a tool for her own self-growth and development. Over the years she has compiled poems written at different points in her life.

“Anytime I had any sort of thought, I always found it was easier to write things in poetry rather than, say, keep a journal. It helped me to put it in a more abstract form and almost remove it from myself in order to deal with it. So that’s how I started to write to begin with,” Dufour says.

Going through a particularly difficult period, she returned to the comforts of pen and paper in order to make sense of herself and her place in the world. With the progression of an eventful last couple of years, slowing down as the pandemic rolled out, Dufour found the perfect opportunity to release her words into the world. She bravely offers raw pieces of herself inked in between pages under public light.

“Local foreigner is the idea of never really belonging anywhere but feeling very much like you do,” Dufour tells me about the title of her book. “For anyone who’s ever traveled around a lot, they’re able to make their mark in a place very quickly but feel that they never fully belong.”

Once thought to be alone in her struggle, she soon realized, growing up, that the sentiment of unsatisfied belonging was a shared experience. Through her passion for creative expression and her knack with words, the book “Local Foreigner” was slowly pieced together. The product is an extension of self as a means to reach those who carry sentiments of being local, but also not, and whose sense of “home” does not fit into conventional molds.

Q: How do you reconcile the question of home?

“Home, I used to think of it as a place, and then over the years, it’s recognizing that it was more of a feeling. Or it was a place in time. I think maybe it’s reconciled in the way that we deal with nostalgia. You end up realizing that maybe it’s not a physical thing, it’s something that you once experienced. And rather than desperately trying to get back to it, learning to live with it as a slightly happier memory, or something that you can mentally take yourself back to for a little moment to get what you need from it, and then step out of it again.”

Q: Is this how Lebanon fits into your understanding of home?

“Yeah, I think so. What was always challenging, and also something else that I’ve been trying to deal with in this book is that because I don’t have the nationality I never really saw it as an option to go back to. I knew it would always be very difficult for me to live there as a foreigner unless I married someone Lebanese to get the nationality. For me, I always knew that it may never be a physical home that I end up settling down in… But the overriding feeling of home in Lebanon for me is just going to be a feeling and who I am.”

Her book is divided into four parts, each one an ode to questions repeatedly asked. “Who are you?”, “What passport do you have?”, “Where is home?”, “When are you coming back?”. Accompanying each chapter is an original art piece by Lebanese digital collage artist Adra Kandil, who has gained popularity through her Instagram page.

Her poems are an almost resistant voice to the confinement of these inquiries. When these seemingly harmless questions are asked, they reiterate the necessity of placement, a prospect which acts as the basis of Dufour’s turmoil with home.

“I tried to resolve all of these different questions that some people ask, usually quite flippantly, but that can have a very big impact on the person being asked,” Dufour says.

Coming to terms with ideas of being an immigrant, a migrant, an expat from multiple backgrounds entails blurring the reductive notions of home as a fixed physical entity and encouraging the understanding of ever-changing internal visions and memories.

After all, home comes with long pasts. We do not simply have a home, but have home created as we are born into environments with rich histories and evolving times. Pain is passed on from generations and attaches itself to understandings of our identities. Dufour’s anthology reads pictures of vivid pain and scarring, reflecting not only the physical bloodshed of war-torn places but the ones that live inside the histories of our homes.

“Like a lot of people from our generation, we experienced our parents war through the way that they brought us up. So that was always very present with me. This stress, this tension that they carried on with them and that I found speaking to a lot of other Lebanese and Arabs around the world, those who had grown up in the Arab world, in the Middle East, and those who grew up elsewhere, but we all have this kind of shared pain that’s been transferred on from our parents,” explains Dufour. “And I think that’s something that no matter how hard you try to get away from it, it’s something more deeply embedded.”

One shared pain flows into another as a different kind of war befalls us at this moment in time. Between the pandemic, October revolution, economic crises, hunger, and the Beirut explosion, many of us have had to reassess and restructure the way we connect with Lebanon as our home.

The Blast acts as a permanent reminder of pain and detachment after it left physical marks on the streets we once knew. Home in Lebanon becomes distant memories of a place now sickly and suffering. Many of us are now forced out of these borders in pursuit of respectable lives, complicating connections to home even further.

As an expat herself, Dufour assures that distance does not relieve any of the pain felt for our country, it is only transformed. Watching one crises after another unfold from within the walls of her London home was difficult in different ways from being present in Lebanon.

“Experiencing all of these different crises from outside, you do always fall into the same pattern. As soon as something big happens, you’re locked in, you want to have as much information as possible, because you’re not able to control it or do anything about it, the only thing you can do is consume information. And I think it always takes a little while to realize that you don’t need to know every little detail that comes up, that you check in on the people closest to you, you keep those support networks, you keep in touch with maybe the main source of information but then you still have to try to live out your life normally. It’s been a challenge. I think it always will be,” Dufour says.

The poem “Beirut” at the very end of her anthology reflects these feelings of helplessness as Dufour describes her personal experience of the Beirut explosion. Confined between small square screens, the vibrations of the Blast could still be felt in hearts living borders away.

While her book is inspired mostly by personal pain and experiences relating specifically to Lebanon and her relationship with it, much of her work proves to be limitless in reach. Many of her foreign friends expressed deep connections to poems that were iterations of very specific memories, like in the poem “Beirut.”

Her poems also exude a timelessness in them, displaying feelings endlessly repeated in history and across human experiences. For example, members of Dufour’s family from previous generations have believed some poems were written in response to recent events but were actually reactions to much older ones.

Q: What surprised you about how people related to your poems?

“The things that surprised me were my non-Lebanese, non-Arab friends who read them and connected to poems that were very, very specifically about Beirut and Lebanon. And that they still managed to see something that related to their life. It surprised me but definitely in a good way in that I realized I was able to create an image or a world that everyone could find something in. And I shared it with some of my family members who English isn’t their first or even second language and they were still able to read it and pick up on a lot of the imagery without too much help which is something really special for me. There is a poem that is very specifically about my grandparents’ house and a lot of my family members who read it could instantly see everything that I was describing, even though they’re not very comfortable with the English language. But I was able to create this world where they could find themselves in.”

Q: What were you expecting people to walk away with or hope people would relate to?

“I wouldn’t say I had any expectations. But I was hoping that people who read it would just start to realize that they’re not alone in how they feel about belonging, about having a home, not having a home because for a very long time I felt I was alone in this and then I started speaking to a few more people, a few more friends and realized that oh no this is a shared experience. So, I just wanted to highlight that for anyone who maybe hadn’t had the opportunity to speak out about it could begin to come to terms with the fact that we’re all a little bit lost. We’re all a little bit disconnected and spread out so, yeah. To not feel so alone.”

Q: How do you make peace with being a “local foreigner” and have you made peace with it?

“I don’t know if I’ve fully made peace with it but I think I’ve grown accustomed to it. I think the more years have passed, the older I get, it bothers me less and less. And trying to see the positives of it in that I can eventually end up belonging in more places than one. I think, when I was younger there was a very strong sense that no, no I had to belong to this place and it really tore me apart that I couldn’t. And then I think just as you mature, you get older, you gain a little bit more life experiences, it’s actually not such a bad thing to maybe be a little bit more spread out. I think it’s still a work in progress, this idea of your finding complete peace with it.

In these troubling and isolating times, Dufour’s poetry anthology reminds us of all the ways we connect as humans. Our prospects of a collective home are not always clear or the same, but the need to feel like we belong, to a place, a people, a cause, or a memory is as palpable as ever.

You can find “Local Foreigner” by Amanda Dufour on Amazon worldwide and various other bookstores online including Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, and Lebanese concept store Dikkéni is currently stocking it on their online store.