Today marks the 18th anniversary of former president George W. Bush’s signing of the Authorization for the Use of Military Force Against Iraq –passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate. Officially, an American born before the war was ever declared can now fight in Iraq.

It’s a grim, if ignored, anniversary as perhaps as many as one million Iraqis have been killed in the war until now. Despite the war “officially” ending with former President Barack Obama’s troop withdrawal in 2011, tens of thousands of troops have circulated in and out of the country since, and thousands of troops remain today.

Leading up the war, the Bush administration and its acolytes –including the current Democratic nominee for President, then senator Joe Biden– bandied about numerous justifications for their disastrous war.

The administration shifted between claiming Iraq possessed nuclear weapons, was an imminent danger to the United States, and, bizarrely, played some role in the 9/11 attacks. There are excellent articles about why each of these claims is false: Iraq did not possess nuclear weapons (nor did they plan to) and the Bush administration was not mistaken at the time. They were lying.

Flimsy as it was, their official story did not cover the true motives for the American war in Iraq. The above articles offer an understanding of just how deeply flawed Bush’s justifications for the war were, but what were the actual motives of the war? Why exactly did the United States invade Iraq, and what did they gain? And, perhaps equally importantly, why did they turn on such a loyal and formidable ally?

An Ill-Fated Relationship: Saddam and the Americans

How do we (the Americans) know Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction? We kept the delivery receipts. This dark joke reveals an even darker history of the American relationship with Iraq.

The “murderous tyrant” who represented the “most serious dangers of our age,” according to George Bush just before the war, was once a crucial US ally.

As late as the Iran-Iraq War, the American government was supplying Saddam with cash, weapons, and biological/chemical agents to use against the people of Iran.

Hanna Batatu, a leading Palestinian historian of Iraq an author of the seminal The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq, goes far further into the past, discussing the United States and CIA’s relationship with Saddam Hussein.

“Permit me to tell you that I know for a certainty that what happened in Iraq on 8 February had the support of American Intelligence,” King Hussein of Jordan said of the 1963 Ba’ath Party coup in Iraq, according to Batatu.

“Numerous meetings were held between the Ba`ath party and American Intelligence, the more important in Kuwait. . . . on 8 February a secret radio beamed to Iraq was supplying the men who pulled the coup with the names and addresses of the Communists there so that they could be arrested and executed.”

Thousands of communists, Kurds, and other opponents of the Ba’ath party were massacred.

These people had been identified by CIA officers from Beirut to Cairo, as well as Iraqi collaborators. The former leader of Iraq, General Abdel Karim Kassem, was tied to a chair in a Baghdad radio station and shot.

The CIA were so ecstatic at these results that James Critchfield, their then-director in the Middle East, later reminisced proudly, “We really had the T’s crossed on what was happening. We regarded it as a great victory.”

So, by the late 1980s, the United States had a friend in Saddam. They had discovered a military minded man who was willing to openly slaughter communists at the height of the Cold War –Saddam’s 1963 coup killed more communists than the US’s 1961 invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs.

Throughout the 1980s, the US supported Saddam’s war against Iran. The Iranians had placed themselves in the Americans’ crosshairs by overthrowing the American-backed Shah –himself installed by a CIA coup– in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Now, the CIA would take some manner of vengeance by siding with Saddam during the war.

Where did this romance go wrong? Only two years after the Americans supported Saddam in the Iran-Iraq War, they would be fighting him in Kuwait. And only ten years after the war in Kuwait, the US would invade Iraq and depose their former associate.

No War(s) for Oil

On July 25, 1990, US Ambassador to Iraq April Glaspie met with Saddam Hussein regarding rising tensions between Iraq and Kuwait, largely the result of an oil and border dispute. We now know what was said during that meeting, as the transcript was leaked by the Iraqi government, and later confirmed by the State Department:

We have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait…the issue is not associated with America….we see the Iraqi point of view that the measures taken by the U.A.E. and Kuwait is, in the final analysis, parallel to military aggression against Iraq, then it would be reasonable for me to be concerned. And for this reason, I received instructions to ask you, in the spirit of friendship –not in the spirit of confrontation– regarding your intentions.

April Glaspie, former US Ambassador to Iraq

The United States would strongly express their opinion on the “Arab-Arab” conflict between Iraq and Kuwait mere months later, by deploying thousands of troops and launching a war against Iraq following their predictable invasion of Kuwait. The US response certainly seems to have been more “in the spirit of confrontation” than “in the spirit of friendship.”

Saddam was under the impression, reasonably so given Ambassador Glaspie’s statement, that the Americans would not interfere in his coming war with Kuwait. The elder Bush, George H. W., clearly felt differently.

He assembled a coalition to remove Saddam from Kuwait. Saddam, once a fast friend, now threatened US oil interests in Saudi Arabia. This could not stand.

The Saudis footed the bill, to the tune of US$32 billion –of the total US$60 billion cost. Despite Iraq briefly taking possession of a Saudi border area, and launching missiles at Israel, the coalition entirely removed Saddam’s forces from Kuwait within 100 hours of invading.

On the advice of military officials, US ground forces did not take the fight into Iraq, and Saddam’s government was left intact following the war.

“I am certain that had we taken all of Iraq, we would have been like the dinosaur in the tar pit –we would still be there,” the American commander of Operation Desert Storm, General Norman Schwarzkopf, warned presciently.

In fact, we are still there. Norman was just mistaken as to which war would make our presence permanent.

The First Gulf War led inexorably to the later American invasion of Iraq. In its wake, Saddam was threatened by not just a hostile Iran as was the case in the 80s, but for the first time, a hostile United States and Saudi Arabia.

He had transitioned from a bastion of Cold War stability for the Americans, to a threat to the international oil trade. While the United States did not remove him following the war, from here on out, that became their goal.

The 90s would be characterized by continued aggression against Iraq and numerous CIA plots against Saddam. It must have been strange for him, being the target rather than the benefactor of such machinations. During the 90s, under President Bill Clinton, Iraq also languished under crippling US sanctions.

Famously, Clinton’s Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, was confronted on the show 60 Minutes about the horrifying humanitarian consequences of these sanctions.

More than 500,000 children alone were killed by US sanctions, and in a chilling interview, Albright called this sacrifice, although not her own, “worth it.”

Although “No War for Oil” would become a common chant at protests during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, it seems just as appropriate when applied to what we can now call, in retrospect, the First Gulf War.

Ok, War for Oil

For those skeptical of the American invasion of Iraq, it seems fairly obvious to point out that this was a war for oil. Everyone from comedians to current US President Donald Trump –who maintains we should continue draining Iraq of oil– have said as much.

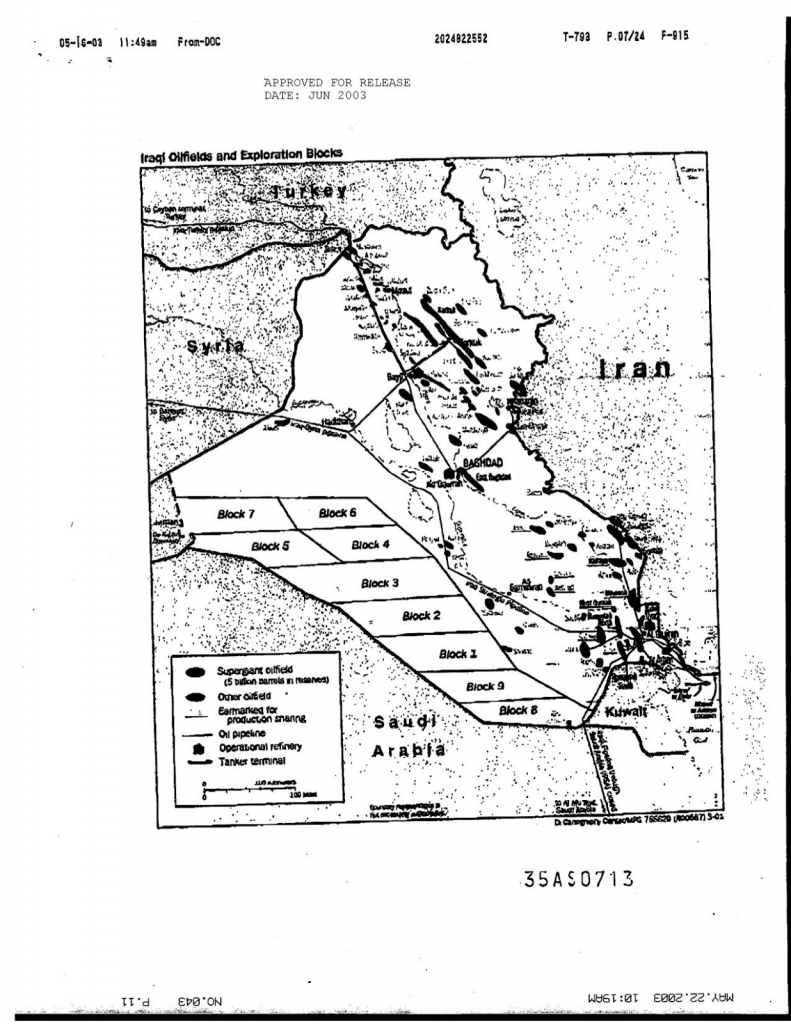

One aspect of this dynamic that goes mostly unexamined, however, is just how early the plan to seize Iraq’s oil was developed. The above map divides Iraq into oil producing blocks, and was accompanied by a list of foreign companies interested in Iraqi oil.

Released as the result of a 2003 lawsuit, the map was produced by Vice President Richard “Dick” Cheney’s energy task force.

Given that Saddam’s government, including the Iraqi oil industry, was under sanction, who would be assisting these foreign companies in exploiting Iraqi oil? Certainly not Saddam. This map envisions a post-Saddam Iraq as early as 2001.

Cheney was intending to remove Saddam, divide the petroleum spoils, and therefore invade Iraq, nearly a year before the 9/11 attacks.

Middle Eastern oil has been on the mind of every American administration since at least the Second World War. For Bush Jr., however, the oil industry dominated his administration to an unprecedented extent.

The Bush family themselves arose from Texas oil, having been tied to the industry since the 1950s. Vice President Cheney was famously the CEO of oil giant Halliburton during the First Gulf War. National Security Advisor, and then Secretary of State Condoleezza “Condi” Rice was a board member of Chevron, which generously and fittingly named an oil tanker in her honor. Even the bin Laden family (yes that bin Laden family) have deep ties to the Bush oil clan.

This background forms the core of the anti-war movement’s “war for oil” argument. In this understanding, the Iraq War was essentially a “smash and grab” operation.

Cheney wanted to secure valuable real estate for his allies in the oil industry, and took out Saddam to clear this path. While this was certainly the case, it misses an important and larger element.

Aside from the pure profit it represents, historian and geographer David Harvey explains just how critical oil is to US hegemony:

If the US successfully engineers the overthrow of both Chavez and Saddam, if it can stabilize or reform an armed-to-the-teeth Saudi regime that is currently based on the shifting sands of authoritarian rule (and in imminent danger of falling into the hands of radicalized Islam), if it can move on (as seems it will likely seek to do) from Iraq to Iran and consolidate a strategic military presence in the central Asian republics and so dominate Caspian Basin oil reserves, then it might, through firm control of the global oil spigot, hope to keep effective control over the global economy for the next fifty years.

David Harvey, The New Imperialism, p. 24-25

The US of course did successfully engineer the overthrow of Saddam. Chavez’s successor, Nicolas Maduro, however, still rules in Venezuela.

Unsurprisingly, the Trump administration –and his campaign opponent, Joe Biden– has framed Maduro as public enemy number one and attempted to engineer his overthrow.

With US forces in firm control of the Iraqi oil spigot, all that remained was for the Americans to extract every ounce of wealth they could.

Reconstruction or Deconstruction?

The US inspector general for Iraq reconstruction released a report, several years ago, regarding the failure of America’s US$60 billion reconstruction effort in the country. He found that, amongst both Iraqis and Americans, the project was a bust.

Senator Claire McCaskill (D-Mo) called the reconstruction an “utter, abject failure” and a “circular firing squad.”

Iraq’s then-acting minister of the interior, Adnan al-Asadi, said, “You can fly in a helicopter around Baghdad and other cities, but you cannot point a finger to a single project that was built and completed by the United States.”

Parsons Inc, one of the largest corporations in the United States, was given the no-bid contract to rebuild much of Iraq’s hospital and clinic infrastructure destroyed by the United States and opposition forces.

Parsons was to build nearly 150 clinics across the country, and paid hundreds of millions of dollars to do so. Ultimately, the firm constructed merely a handful (nearly a dozen) despite contracts in Iraq that came to a total of two billion dollars and spanned nearly every sector of the economy.

Bechtel Corporation held contracts even more vast in scope than those of Parsons. One of the more high profile Bechtel projects was Laura Bush’s (George’s wife) proposed children’s hospital in the Iraqi city of Basra.

The project, first begun in 2003, was not completed until 2010 –five years behind schedule. The budgeted cost for the project was a staggering 50 million.

However, the price further soared, eventually totaling more than 170 million dollars.

If these logistical issues were not severe enough, the public goal of the project equally doomed it to failure.

Iraq was suffering from a lack of the most basic of resources: hospitals were completely overbooked, 90 percent of them suffered severe equipment shortages, and Yarmouk Hospital lost five patients each day due to lack of equipment.

In this environment, where patients die due to power cuts and faulty generators, the Bush administration sank money into constructing one of the most overly-complicated hospital structures imaginable.

While the public health sector was being ruthlessly privatized, other segments of the Iraqi economy suffered the same fate. When the decision to undergo a path towards privatization was taken by Mr. Paul Bremer, the Administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq (a man who had the most power of an American civilian since the reconstruction of Japan, wielding authority akin to that of a British Viceroy), there was a fear among the American ruling elite that that the Iraqis would view the process as a means for foreigners to loot their country.

That being said, these concerns were largely ignored, and during the privatization process, foreign companies were able to purchase 100 percent of every sector of the Iraqi economy, apart from natural resources.

Bechtel was the largest single participant in this process. Their contracts totaled more than 100 million. The company constructed power generation facilities, electrical grids, municipal water systems, sewage plants, airports, and even schools and ministry buildings.

This was all accomplished through yet another no-bid contract, without any money flowing into the Iraqi economy. Water was, shockingly, not considered a natural resource, and thus Bechtel was able to acquire the lucrative contracts to the water industry in Iraq.

The logical question that arises from this is “why Bechtel?” Bechtel did not have a sterling record even in regards to its prior US-based contracts.

Its Boston Tunnel Project was budgeted for 2.5 billion and was completed late for a total of 14.6 billion dollars –1.8 million dollars a mile. The tunnel later collapsed on a woman, killing her. Additionally, while building a nuclear power plant in California, Bechtel managed to install one of the 420 ton reactors backwards.

The Empire Strikes Back

Niall Ferguson, a British imperial historian and cheerleader of the Iraq War, compares the American logics of empire unfavorably with the British.

As Ferguson puts it, the British were in the empire game for the long haul. They would deploy endless troops and resources to secure the more far flung reaches of their empire.

The Americans, in the estimation of Ferguson, are far less committed to their own imperial project. Ferguson points to the raising, and then pulling down, of an American flag over Saddam’s statue in Baghdad’s Firdos Square.

Out of fear of poor optics, it was quickly replaced by an Iraqi flag. Seeing this, Ferguson laments, “You didn’t have to wait long for a perfect symbol of the fundamental weakness at the heart of the new American imperialism –sorry, humanitarianism.”

Is this weakness? The Americans are still in Iraq, and have since intervened in Libya, Syria, and Yemen, to name but a few.

American imperialism seems alive and well, and quite powerful. Ferguson, however, does have a point. America, and Americans, still flinch at labeling their country an “empire” and its actions “imperialism” in a way that their British predecessors never did.

America’s rejection of a formal empire is not “weakness,” but merely adaptation. American imperialism in Iraq has taken a far different form than earlier modes of European colonialism/imperialism.

The actions of the United States in regards to Iraq can be understood as a logical, if misguided, response by policy makers to a domestic crisis of overaccumulation –when a capitalist core country becomes flush with either capital or labor, as was the case during the US Recession of 2000.

This is the core of the logic of America’s capitalist imperialism, whereby states seek to resolve crises of over-accumulation via territorial expansion. Essentially, the US was searching for an outlet for its excess capital, which, given the recession, could not be invested profitably domestically.

Iraq presented a highly effective fix for the United States. US companies were able to dominate entirely new markets, raking in massive profits and receiving funds from the government. To explain that these firms were ineffective in delivering services or “rebuilding Iraq” is correct, and important to note, but also misses the point.

They may have been ineffective in those respects, but certainly served their two prime functions: to make a profit off of a captive, occupied nation, and to serve as a profitable dumping ground for US capital.

While the CEOs of Bechtel, Parsons, and Halliburton did not command the first American gunships to land in Iraq –although Halliburton’s ex-CEO did– it is impossible to overstate these corporations’ influence on the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Here it seems that the interests of the ruling class diverge from the direct, short-term interests of a state considering that the US government spent billions during the war, and lost thousands of soldiers.

While the “reconstruction” of Iraq was successful in looting Iraqi society, it remains to be seen if this imperial project will be successful in the long term. Thus, while there were no nuclear weapons, Saddam had nothing to do with either Al-Qaeda or 9/11, and the US failed to “rebuild” Iraq successfully, it is entirely possible to consider the Iraq War a “success.” It was, at least it was for those segments of the ruling class it was truly meant to benefit.

The US, in one move, managed to secure the Middle East oil spigot, set up lucrative contracts for construction firms, and force Iraq to open for foreign investment. For the elements of American capital interested in such matters, the war served its purpose.