Following the explosion at the Beirut port, France has returned to its old colonial subject, Lebanon. As French President Emmanuel Macron takes a brief respite from cracking down on protestors in his own country, he’s fixed his gaze on the Lebanese government. He attempted to set a deadline for government formation, which was not met.

However, his involvement appears far from over. In this, he is not alone, with the United States approaching Lebanon following the disaster like a moth to a candle.

As the two work in tandem, their main target appears to be Hezbollah, long labelled a terrorist organization by the United States. Macron met with Mohammed Raad, leader of Hezbollah’s bloc in the parliament, and demanded that the group cut ties with Iran and withdraw from Syria. This demand was coupled with several demands/threats from United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

“The United States has assumed its responsibility and we will stop Iran buying Chinese tanks and Russian air defense systems and then selling weapons to Hezbollah (and) torpedoing President Macron’s efforts in Lebanon,” Pompeo told France Inter radio. “You can’t allow Iran to have more money, power and arms and at same time try to disconnect Hezbollah from the disasters it provoked in Lebanon.”

Given that the entire political ruling class of Lebanon, as well as many international institutions, seem responsible for leaving tons of ammonium sitting in the port, this is an odd accusation. Unless, of course, France and the United States have no intention of helping Lebanon construct a so-called “neutral” government, and are instead attempting to push an old geopolitical rival out of power.

A (Still) Sectarian Post-Blast Order

Even before this explosion, France and the United States had a keen interest in developments in Lebanon. Both countries (as well as the IMF and World Bank) sponsored repeated international conferences, ostensibly to buttress the Lebanese economy.

Realistically, these types of conferences and reforms push austerity and neoliberalism. However, Dr. Hicham Safieddine, of King’s College London, reveals an interesting secondary purpose: “These conferences were never a purely economic or financial matter. Backing these governments was an attempt to shore up Hezbollah’s adversaries after geopolitical gains by the latter.”

Each of these conferences took place under the leadership of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, his son Saad, or their ally Fouad Siniora. This allows an understanding of these conferences as not merely attempts to force privatization and other reforms, but also an attempt to forge a Lebanese government more compliant to Western demands.

This dynamic is equally clear today. The pressure France has been placing on Lebanon to “form a government” is specific, not general. Not just any government will do.

The current government crisis centers around the Ministry of Finance, long held by the Shia political bloc in Lebanon. Under the French plan for the Lebanese government, this post would no longer be rooted in a sectarian distribution of power.

However, the two others posts which traditionally sign decrees, the President of the Republic (a Maronite) and the Prime Minister (a Sunni) will retain their sectarian affiliations. Coincidentally, the holders of these posts tend to be French/Western allies.

Hezbollah and Haraket Amal (the two Shia political parties) are continuing to insist that the Ministry of Finance should be allotted to a Shia, while the French maintain that their intransigence will “stall the formation” of the new government.

What much of the media is covering as “impeding the government” is just as easily understood as a defensive measure to avoid being pushed out of political power, undertaken by the sect both most hostile to US interference and historically most disenfranchised ( particularly before the rise of Hezbollah) in Lebanon.

Patriarch Bechara Boutros Al-Rai, of the Maronite Christians, also entered this sectarian fray. He appeared to condemn the entire Shia sect, asking, “In what capacity does a sect demand a certain ministry as if it is its own, and obstruct the formation of the government, until it achieves its goals, and so causes political paralysis?”

This seems easier to question if the sect you oversee is guaranteed the Presidency. The argument of the two Shia parties would be, and is, that this move represents purposefully freezing them out of political power.

“The isolation of the Shia leadership comes at the wrong time, during a period in which the United States is being intractable with everything that has to do with Iran and its allies,” explains Joseph Daher, scholar and author of the book Hezbollah: The Political Economy of the Party of God.

President Donald Trump’s government has made no secret of its desire to curtail Iranian influence in the Middle East, and therefore remove the only serious opposition to US hegemony in the region.

As Daher says, this isolation of the Shia in Lebanon is part of a much wider pattern. From leveling sanctions at Lebanese officials, to the assassination of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani, to coordinating with Israel to conduct illegal operations against Iran, the US is tightening the noose around those with the audacity to push back on their agenda.

While Macron has resisted the dramatic move of condemning Hezbollah’s political arm as a terrorist organization, the French government (and that of the EU) seem desperate for him to do so.

A petition has been signed by French former prime ministers, foreign ministers, and various other party notables demanding that Macron take an even harsher stance against Hezbollah, and support the European Union in blacklisting them.

Has Macron, though to a lesser degree than Trump, not already proven his anti-Hezbollah credentials by discussing the removal of Hezbollah’s weapons with Israel, Lebanon’s historic invader?

Also during his reading with MP Mohammad Raad, Macron intoned, “We know your history very well…do you want to help the Lebanese, yes or no?”

Raad could have just as easily flipped the question back on the French President, as those who know the history of French involvement in Lebanon, particularly their early desire to create a Christian state, surely would share the concern.

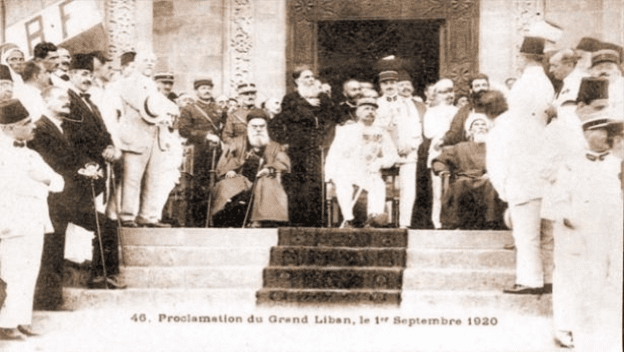

The “Picot” of Sykes-Picot: Empty French Promises to the Lebanese

“France would never consent to offer independence to the Arabs,” declared an imperious Georges-Picot (A Line in the Sand, James Barr).

Picot, the former French Consul-General of Beirut and later High Commissioner of Syria, is perhaps most famous for his role in the disastrous “Sykes-Picot” agreement, in which he and British foreign minister Mark Sykes divided the Middle East between Britain and France, in the event of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

He has a deeper history, however, in Beirut specifically, one which may prove revealing of France’s current position.

The very name “Martyrs’ Square” and the statue that sits in its center serves as a grim reminder of the false promises made by the French to the people of Lebanon.

In June of 1914, Georges-Picot became aware of increasing demands for the independence of Syria and Lebanon. Hoping to further the French’s historical good relations with the Lebanese Christians, Picot secretly arranged the delivery of fifteen thousand rifles to the Lebanese to support a rebellion against Ottoman authorities.

At the onset of the First World War, Picot of course fled Lebanon. Leaving Beirut by boat, he told his newly armed compatriots, “See you in a fortnight [two weeks].”

After a fortnight, Picot expected to return at the head of a French army to “liberate” Lebanon. Not only did this French army never materialize, but Picot never destroyed his letters and correspondence with potential revolutionaries. He instead left them with the Americans.

The Ottomans quickly discovered the letters, and promptly executed all those involved, save Monsieur Picot of course, who was safely residing in Paris. His less fortunate co-conspirators are still memorialized in Martyrs’ Square, dual victims of Ottoman repression and French incompetence/imperial meddling.

The history of the French Mandate, and its role in the fall of the Ottoman Empire, still looms large today. “Mr. President, you’re on General Gouraud Street; he freed us from the Ottomans. Free us from the current authorities,” asked one protestor of President Macron.

French General Henri Gouraud, High Commissioner of the Levant, however, was fully aware that what he was bringing to the Levant was anything but freedom: “It will be easy to maintain a balance among three or four states that will be large enough to achieve self-sufficiency and, if need be, pit one against the other” (20 August 1920, Archives of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, vol. 32, pp. 188–9) the general noted.

The French have continued their legacy of pitting one group against another, furthering sectarianism and division, and treating the Middle East like their own sandbox. When it comes to Lebanon, the French have a clear lead in constructing sectarian governments over their American partners. However, the Americans seem to have been practicing this technique more recently in occupied Iraq.

Iraq: How to Create a Sectarian Nightmare in Three Easy Steps

When most people think of Western involvement in sectarianism in the Middle East, they think of markers like the Sykes-Picot agreement or the Balfour Declaration. While these are certainly important moments, the focus on them can obscure more recent history, which reveals a deep commitment by the West to furthering sectarianism.

As the French seem to be coupled with the Americans in building a new sectarian order in Lebanon, the latter’s history lies in constructing the post-war sectarian battlefield in Iraq.

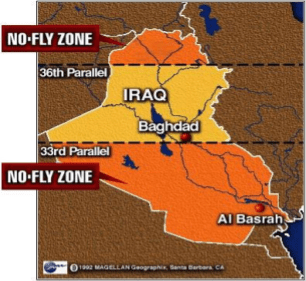

In fairness, it took the Americans far more than three steps to engender sectarianism in Iraqi society, it was a project that developed over decades. When the United States designated Saddam Hussein’s government as an enemy (after years of supporting Saddam’s crackdowns on communists and war with Iran), they followed a policy of approaching Iraqi society via their various sects, as the British before them had during the Mandate years.

Throughout the 90s, the United States and United Kingdom (again, the Mandatory power returns) enforced no-fly zones over portions of Iraq. Specifically, they patrolled the majority-Kurdish north and majority-Shia south. This, along with the sectarian application of the UN’s Oil-for-Food program, set the stage for sectarian upheaval during the American occupation.

Nearly 50 percent of the marriages in Iraq were between members of different religions as late as 2003, the year the United States assumed control of the country. Throughout the occupation, interfaith marriages became so rare as to inspire headlines.

Given the US’s interest in forging a new government in Lebanon, and determining who remains in power and who gets pushed out, the question of how exactly this happened is of paramount importance.

The CPA (Coalition Provisional Authority) was the structure via which the Americans ruled Iraq following their takeover. The Coalition’s (it was largely a coalition of one, the United States) very first decree was the so-called “De-Ba’athification” of Iraqi society and government.

At least 30,000 members of the ruling Ba’ath party lost their jobs. The party was largely comprised of the ruling Sunni minority, who the United States viewed as a threat to their new political order, and new Shia allies.

The attempts to freeze Hezbollah and Haraket Amal out of the Lebanese government, regardless of anyone’s opinions of these two parties, should ring familiar.

For a country which so vehemently argues for its own citizens’ “right to bear arms” and carry weaponry, the United States seems incredibly preoccupied with disarming groups not to its liking across the globe.

It does this with almost as much zeal as it arms those who serve its purposes, from the Taliban in the 80s, to the Israeli army, the Saudis, and Al-Nusra Front.

The United States has pushed to disarm its rivals in both Lebanon and Iraq. In Iraq, they disbanded the entire Iraqi army, causing massive discontentment and an accompanying employment crisis.

They seek a similar arrangement in Lebanon, where they hope Hezbollah, who fought the Israelis each time they invaded the country –unlike the Lebanese army– will have their weapons stripped from them. It seems obvious that they both cannot and will not demand the same of the Israeli army, an organization responsible for far more civilian deaths across the Middle East than Hezbollah.

France and the United States are not seeking an end to Lebanese sectarianism, only a rearrangement of it. Judging by their actions in both the critical month after the Beirut explosion and historically, they would not attempt to resolve sectarian conflict in Lebanon even if that were within their power.

After all, France’s interventions in Lebanon, both under the Ottoman Empire and during the Mandate, largely inspired Lebanon’s sectarian quagmire. The United States made explicit use of sectarianism as a mode of control during its war against the Iraqi people.

In short, if Lebanon was looking to further political gridlock, entrench sectarian divisions, and set the stage for an even deeper financial crisis, they really couldn’t do better than look to France and the United States.