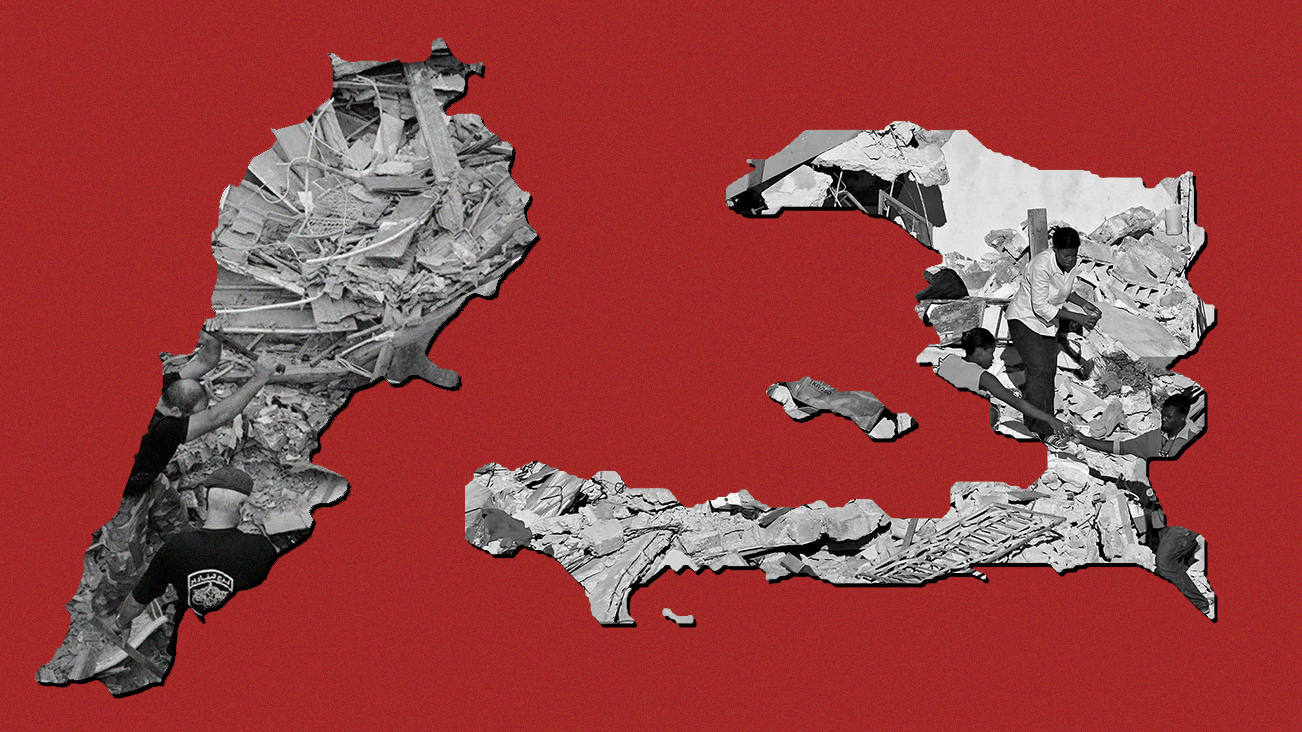

As the weeks pass since the devastating explosion in Beirut’s port, an increasing number of foreign governments, international bodies, and non-government organizations have lined up to donate money, or physical aid to Lebanon.

While Lebanon is clearly in need of assistance, this assemblage of saviors, often referred to collectively as the so-called “international community” has a mixed record at best, and, perhaps more importantly, have interests of their own they will pursue. That said, there is widespread damage across Beirut, and the port is still only partially operational.

Particularly in regard to the port, it seems the Americans and the French are taking the lead. French President Emmanuel Macron arrived in the country on August 6, two days after the blast. He was greeted by an adoring crowd, one of whom begged him, “Mr. President, you’re on General Gouraud Street; he freed us from the Ottomans. Free us from the current authorities.”

He was also greeted by a petition, signed by 50,000 people, requesting France reassert colonial control over Lebanon.

Echoes of Haiti

Lebanon will not be the first (nor, I suspect, the last) former colonial possession to receive “assistance” from France and the United States. “Our hats off to Barack Obama because he is sending his people to take control of the country! Haiti should become part of the United States!” proclaimed a member of a Haitian crowd in Jonathan Katz’s seminal book on the aid industry in Haiti, The Big Truck That Went By.

This comparison is not merely superficial, as Haiti provides another example of a former French colony experiencing a massive disaster, and then receiving extensive aid from France, the United States, and a litany of international institutions.

Emmanuel Macron and Michelle Obama receive similar welcomes, returning to territories once owned by their respective empires.

There is, however, a darker connection between these two efforts which may determine the effectiveness of the “aid.” In both the Haitian and Lebanese cases, aid is being offered and reform suggested by the same actors who built the economic conditions which made these disasters so devastating.

In January of 2010, Haiti was hit by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake which left hundreds of thousands dead, as well as hundreds of thousands of buildings destroyed. Following the disaster, nearly $15 billion flowed into the country. The ultimate destination of this money, as well as its origins, is certainly important. One specific example of mismanagement stands out.

Before Beirut’s Port, There was Haiti’s

Of particular interest to the Lebanese should be the failed attempt to rebuild Haiti’s port. This was an effort largely undertaken by the United States, which had occupied Haiti for nearly twenty years.

In more recent history, under President William Clinton, the US again invaded the country in 1994, during the chillingly named Operation Uphold Democracy. This operation reversed a military coup and returned Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power. His reign would be short, however, as ten year later the US grew displeased with Aristide and backed a group of right-wing paramilitaries to remove him from power (again).

All this to say, the US, like France in Lebanon, was not neutral in Haiti. From its earlier period of colonial control to the intervention of the Clinton administration, the US pushed neoliberal policies and free trade in Haiti. Their project “rebuilding” the port was steeped in this tradition.

There was no greater embodiment of the neoliberal approach to aid in Haiti than the US’s largest post-earthquake project –a $300m, 600-acre industrial park called Caracol, on the country’s northern coast. To make the park more attractive, the US also agreed to finance a power plant, and a new port through which firms operating at Caracol could ship in materials such as cotton, and ship out finished products including T-shirts and jeans.

Jacob Kushner, The Guardian

This project required a new port. At the insistence of the United States, and US-based donors, the old port was to be abandoned in favor of a different location of more use to the planned industrial park. To this day, this new port does not exist.

The Government Accountability Office (responsible for ensuring the US government’s money is being well spent) did an audit of USAid’s program, with a focus on the port, in Haiti. The report found that USAid had failed to hire a supervising engineer for the project, and vastly underestimated the money and time it would take to complete building a new port and power plant.

As costs continued to rise, and the engineer position remained unfilled for years, USAid quietly cancelled the project in 2018, three years after this new port was supposed to be completed, and eight years after the earthquake.

There is a stunning coda to the failure of the port. After the project was canceled by USAid, a US-based journalist decided to visit the old (largely destroyed) port to report the reaction of the authorities there.

When I visited Cap-Haïtien in December, Haitian port authorities were unaware that USAid had scrapped the project. “Last conversation we had, they told us the money is there,” Anaclé Gervè, the director of the Cap-Haïtien port, said. I told him what a USAid official told me: it had decided to cancel the port project six months earlier. Gervè leaned back in his chair. “Wow,” he said. “They didn’t tell us that.” When I asked Gervè what the US’s $70m had achieved, he pointed to two concrete electricity poles, erected as part of a plan to connect the port to the public grid. USAid had paid for the poles, but had not strung the cables needed to electrify them.

Jacob Kushner, The Guardian

There is no further information regarding where that $70m ended up, but it certainly did not construct two concrete polls. It took six months for the director of the port to find out construction was cancelled. Not only that, but he only eventually found out because of a journalist.

After the utter failure of the port project, it is fair to question if the US was ever even capable of shepherding large real estate projects in Haiti. To be fair, there was one unqualified success. The largest land plot in post-earthquake Haiti was the new Marriott hotel in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital.

Too Corrupt to be Trusted?

In both Haiti and Lebanon, Western powers have stressed that the local governments (and often other organizations) are too corrupt to be trusted with vast sums of money. In Haiti, this meant largely bypassing the Haitian government, and having foreign NGOs, international bodies, and states, determine the character of reconstruction.

After April 2010 and until October 2011, the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (co-chaired by Bill Clinton) and not the Haitian parliament, made decisions as to how reconstruction would advance. This, again according to Katz’s The Big Truck That Went By, led to a dangerous misconception:

The irony was that, by keeping the money under their own control, the donors reinforced the perception of systemic Haitian corruption.…many—if not most—Haitians were also under the misapprehension that aid money went to the Haitian government. If money were pledged but not delivered, they assumed their leaders had stolen it. And it was a rule of donors’ conferences that pledges were not typically delivered.

Jonathan M. Katz, The Big Truck That Went By

This loss of sovereignty was thorough, but not entirely unavoidable, had a different path been taken. Even Marie St. Fleur, a Haitian-American member of the Massachusetts statehouse, thought the proper role of the international community was to “support and not supplant the role of the state.”

She added, “Haiti’s sovereignty is best protected when we invest in building the capacity of the state to take care of its people.”

Lebanon must tread this road carefully. While Lebanese NGOs (such as the Lebanese Red Cross) have proven effective in responding to the crisis, there is no reason to expect the same from international bodies.

Fear of corruption, however, never seems to extend beyond the global south. Haiti and Lebanon surely both have corrupt governments by some standards, but compared to what? Compared to the government of the United States? Or compared to the “international community” and its chosen aid dispersal methods?

It is difficult to imagine that, even in the worst case scenario, the Haitian government (or the Lebanese, for that matter) could have been less efficient than the American Red Cross.

An investigation conducted by ProPublica, an organization dedicated to investigative journalism and uncovering corruption, came to a shocking conclusion in its aptly titled report, How the Red Cross Raised Half a Billion Dollars for Haiti and Built Six Homes.

Yes, the Red Cross only built six permanent houses in the entire country of Haiti, after receiving half a billion dollars in donations. While the Red Cross maintains it has provided homes to more than 130,000 people, ProPublica revealed that this figure relies on counting tents and aluminium huts as houses. For half a billion, one might expect more quality aid.

To add insult to injury, Red Cross managers implied that part of its problem stemmed from the idea that “talented, smart, competent Haitians cannot be found in Haiti.” It now seems far more likely that talented, smart, competent foreign NGOs and government representatives cannot be found in Haiti.

Blue Helmets in Lebanon and Haiti

One unusual trait Haiti and Lebanon share is the presence of the United Nations. Each country played host to a massive UN force even before their respective catastrophes.

In Lebanon, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) was established in 1978, ostensibly to enforce the border between Lebanon and Occupied Palestine.

In Haiti, the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (known by the French acronym, MINUSTAH) was established in 2004 following the American-backed coup to “enforce order.”

The UN’s presence in Lebanon is particularly relevant to the post-blast order for two reasons. First, the UN has already suggested they be involved in any investigation of the cause of the explosion in the port as “independent” investigators. The second, and related, reason is that questions have already begun to arise as to the UN’s role in the systemic failures that led to the explosion.

Lebaenese Customs Chief Badri Daher, one of those arrested following the explosion, is now claiming that UNIFIL forces cleared the Rhosus, the ship carrying the ammonium nitrate into Lebanon, to enter the country.

The UN denied this claim, insisting that inspecting ships and clearing them for entry is not their job. However, UNIFIL’s mandate tells a different story.

The Maritime Task Force, operating under the UNIFIL umbrella, has wide sweeping authority. They are free to operate along the entire Lebanese coast, with their jurisdiction reaching out 48 nautical miles into international waters.

UNIFIL’s own press kit describes the Maritime Task Forces’s responsibilities as “monitoring the Lebanese territorial waters, securing the Lebanese coastline and preventing the unauthorized entry of arms or related materiel by sea into Lebanon.”

Enough ammonium nitrate to level half a city seems to fall under the category of “unauthorized entry of arms or related material.”

We know that 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate entered the country by sea after sitting on a cargo ship for nearly a year. Of course it is not clear when, or if, UNIFIL was aware of this danger, but the UN seems far from partial in this matter. Although the UN ardently denies responsibility, anyone aware of their actions in Haiti will certainly doubt if this is true.

In Haiti, UN peacekeepers started a cholera epidemic that killed more than 9,300 people and made another 800,000 sick.

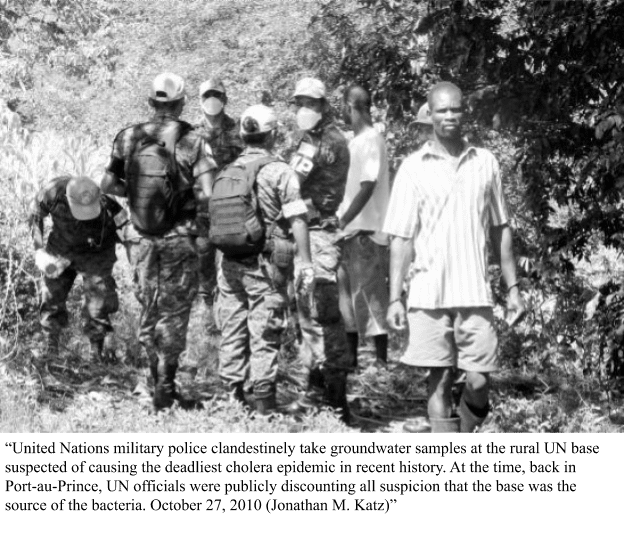

Jonathan Katz revealed that the UN had long been aware of its unsanitary practices at its various bases across the country, particularly those in rural areas, and covered up their complicity in this horrific crime.

The UN first argued that such an outbreak was the inevitable outcome of the destruction and chaos brought on by the earthquake. If this was the case, why did the outbreak begin just downstream from a rural UN base, forty five miles north of the epicenter of the earthquake, and nine months after the quake itself?

Investigators have since found that, “There was no on-site treatment for wastewater at the UN base. Once the outbreak began, the UN soldiers themselves drank water filtered through a high-quality process chain including filtration, reverse osmosis, and chlorination,” (Katz, The Big Truck That Went By).

Haiti’s water, into which the UN was leaking sewage, was known to be too dangerous for the UN officers themselves to drink, but apparently the UN did not extend the same concern to the people of Haiti. The image below shows the UN testing water samples outside their base, while they were still publicly denying all responsibility.

International Cops: Who will Investigate the Beirut Blast Site?

If only the ‘international community’ is trustworthy enough to provide aid, are they also the only ones able to conduct this investigation into the cause of the explosion at Beirut’s port? Many in Lebanon already seem to think so.

The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) will be joining the investigation into what ignited this ammonium. Any resistance to the idea that the FBI or other international forces should enter Lebanon and investigate this crime is seen as complicity in the explosion or corruption.

After all, if you are not guilty, what do you have to fear from the FBI? For the answer to this question, one need look no further than their harassment and perhaps eventual killing of Martin Luther King Jr., or their contributions to American torture sites.

Much of the international community is already committed to doing an investigation, and insisting it must be undertaken “independently” (read: by the Americans and their proxies). American think tanks (contracted by the state) have already begun laying the groundwork for the inevitable conclusion of any American-led investigation:

It would make sense to recognize that the horror and tragedy of the Beirut blast presents an opportunity to trim the sails of Iran’s most effective regional proxy, Hezbollah…. this is a golden opportunity. Holding Hezbollah accountable for perhaps killing hundreds of Lebanese and injuring thousands could push the Lebanese people—and Western public opinion in general—to reject Hezbollah’s grip on the country.

Hanin Ghaddar, Foreign Policy

Sorry, did we all miss the investigation? The Special Tribunal for Lebanon took the better part of a decade to release its “findings” on the killing of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, but it seems the FBI and the French may have come to their own findings before a true investigation of the port has even begun. It would be a critical error to view an international investigation as “neutral” in any important sense.

Aid is Never Neutral

Lebanon faces one severe problem that Haiti did not. While the US has long abused human rights in Haiti, and still to this day seeks to impose neoliberal reform on the country, the US has not declared any Haitian political parties “terrorist organizations.”

This is of course not the case with Lebanon. Unfortunately, much of the aid coming into Lebanon carries a more sinister purpose than disaster relief: the removal (or exclusion) of Hezbollah, a political party whose agenda runs counter to that of the United States.

USAid, which nominally exists as an outlet for US economic investment in developing nations, has long been involved in regime change.

The organization’s relationship with US intelligence, particularly the CIA, is somewhat of an open secret. In Bolivia and Venezuela, USAid regularly funds opposition parties, works with private military contractors, and supports separatist movements in resource rich areas.

USAid’s most bizarre coup attempt, however, took place in Cuba. USAid was not delivering aid to Cuba, but rather a strange Twitter knock-off called ZunZuneo.

USAid’s goal was as simple as its method was complicated. The goal? Overthrow the Cuban government. The method? Create a social networking site, using hidden bank accounts in the Caymans, that appears like a Cuban website yet is operated by US intelligence. Even the US Congress was unaware that the federal agency for “aid” was acting like a spy outfit:

There is the risk to young, unsuspecting Cuban cellphone users who had no idea this was a US government-funded activity. There is the clandestine nature of the program that was not disclosed to the appropriations subcommittee with oversight responsibility.

Patrick Leahy, Senator from Vermont

USAid appears to have left the “humanitarianism” at the door, only espionage from this point onward.

On one day the US reaffirms its commitment to helping Lebanon recover, while the next, the Trump administration announces a new round of sanctions, taking advantage of this tragedy to score political points. This contradiction seems insurmountable.

Unless, that is, one views the sanctions, politically contingent aid, and US (FBI) investigations as a holistic strategy to bring the full force of US soft power to bear against Lebanon.

While Lebanon is certainly reeling from the port explosion, the country is not yet as vulnerable as Haiti was following the earthquake. With any luck, Lebanon may be in a slightly better position to deny the circling vultures, again.

International bodies, foreign powers, and Western NGOs pose a unique danger to countries like Lebanon. Their actions are more invisible than those of the state, and their power is far more diffuse. Who can you protest? Who can be forced to resign? What can anyone, from Lebanon to Haiti to the United States, vote against?

The current Lebanese government has proven its inability to deal with crises, and had largely set in place the neoliberal structures which allowed this tragedy. Exactly the same can be said of the so-called “international community.”