Sporting Club Beach has denied entry to a woman, her daughter, and her mother because the mother was donning a veil.

Farah Shoucair, the woman in question, took to Twitter on Sunday to voice out her experience at the beach resort.

“Sporting Club did not allow me or my daughter entry because my hijabi mother is with us. My mother, who has welcomed my romantic relationship with a Lebanese man (coincidentally Christian) and my civil marriage to him, was not allowed entry to sit at the Club’s coffee shop. This is #Beirut 2020. This is #Lebanon 2020. An open farm for racist and sectarian people,” she wrote.

As of Monday morning, Shoucair’s tweet has garnered around 1.6K retweets and 6K likes as a social media storm imbued. Activists, politicians, journalists and more soon took to Twitter to debate the matter.

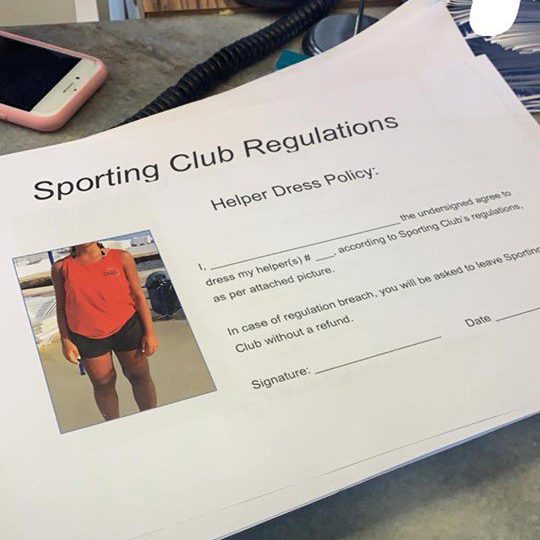

Similar to other beaches in Lebanon, Sporting Club has been known to practice another form of discrimination against migrant workers by not allowing them to swim in pools and setting a “helper dress policy” that employers must sign before entry.

In one tweet, political satirist Nadim Koteich stated that as a private beach, Sporting Club “are entitled to their own rules. I personally won’t go if they allow veiled women.”

Koteich was a guest on Marcel Ghanem’s Sar el Waet this past Thursday, where he took the opportunity to fiercely advocate for bypassing sectarian differences in the name of unity and tolerance.

“You can’t be with all rights and freedom etc…and prohibit a veiled woman from going into any place public or private,” wrote back twitter user Abdallah Zaher.

@NadimKoteich

You can’t be with all rights and freedom etc… and prohibit a veiled woman from going into any place public or private!!

That draws me to the only conclusion that you’re an islamophobe probably.— Abdullah Zaher (@AbdullahZaher3) July 5, 2020

Another tweet by Sporting Club lawyer Karim Majbour, the lawyer who spearheaded the lawsuit against accused harasser and rapist Marwan Habib, stated that Shoucair’s tweet falls within the realm of defamation and lies.

Majbour, like Koteich, advocated that Sporting Club are entitled to their own rules, despite the discriminatory nature that they may adopt.

“You cannot enter someone’s house and not respect their rules. The problem with Lebanon is that you don’t know how to abide by the law!” wrote Majbour.

Majbour later released a statement saying that Sporting Club denied them entry to the pool area because no one is allowed to be there without swimwear, but welcomed the women to the cafeteria area.

On the other end of the spectrum, journalist Dima Sadek took to condemning the club and inciting that boycott was necessary.

Just last week, another debate ensued on social media after Sheikh Abbas Hoteit controversially posted a picture on Facebook of a girl in a bikini at a beach in Tyre, a city in the south of Lebanon. The picture was later found to have been taken without the girl’s consent.

The Sheikh took to social media to protest this woman’s actions, terming them a “social catastrophe” and a “dangerous situation.” He expressed fear that Lebanese beaches were starting to resemble Western ones, and even called for society to cover up its women.

Last week, it was a Sheikh telling women to cover up. This week, it’s a beach club telling women they’ve covered up far too much.

Discrimination seems to not be exempt from the conversation, even as the country battles bigger issues, such as the worst economic collapse in its history.

Feminist discourse proves more and more essential for Lebanese citizens every day. Only when we, as a Lebanese society, understand that a woman reserves the full rights to do whatever she pleases with her body may we begin to dissect and move past our prejudices, and perhaps really learn to coexist.

Coexistence is not limited to religious and sectarian co-existence, or to pictures of a mosque and church right by one another in Beirut’s central district. It is necessarily inclusive of the acceptance of women as independent agents who are entitled to their own freedom of expression.