Whenever a trailer comes out and I hear people’s responses, I’m usually the guy that breathes words of caution: that you shouldn’t judge a 90-minute film by its trailer. Mostly I try to avoid them all together, preferring to enter a film knowing nothing of what’s to proceed, running only on the posters, which are almost impossible to avoid. Yet, the trailer of the upcoming film ‘Beirut’ seems to spell out enough for any critical viewer to see in advance what the film will be: Imperial Orientalist tripe.

Most of the responses thus far have been focused on the violent depiction of both Beirut and its natives. People seem furious, and rightly so, that the film includes no Lebanese actors, is not even shot in Lebanon and yet feels entitled to tell our story as though it’s their own. Yet, when I first watched it, it was something else that struck me as both disgusting and potentially dangerous. It was one line: “2000 years of revenge, vendetta and murder. Welcome to Beirut”. This isn’t just an inaccuracy, it is the rewriting of history to suit a very specific prevailing power relation between the West and the Middle East. It is this historical revisionism matched with really-existing American imperialism that troubles me most about the release of this film.

The Depiction of Arabs through Orientalism in Film

I don’t want to spend too much time explaining why this film is Orientalist, because it seems quite self-evident. It is Orientalism at its most fundamental. The mere fact that it is a film about the East produced by the world hegemonic and regional military power, the United States, highlights the film’s failure to depict Beirut with any semblance of objectivity. By recreating the East on screen, they are in essence dictating the narratives and our character for themselves.

The depiction of Arabs is just ridiculous and cannot be described by anything other than the O word. For instance, there are only two types of Arabs in the trailer, terrorists and children. Arabs never get to speak critically in film. They are either innocent and soon to be corrupted, or already are corrupted, violent and speak in absurdly bad English. The repercussions of such a reductive world view can best be illustrated through Edward Said’s words on the Invasion of Iraq: “Without a well-organised sense that these people over there were not like “us” and didn’t appreciate “our” values — the very core of traditional Orientalist dogma as I describe its creation and circulation in this book — there would have been no war.”

Of course this isn’t the first film to portray Arabs in a two-dimensional, villainous and simplistic manner. So many films come to mind: Hurt Locker, American Sniper, Black Hawk Down, to name a few. A good comparative example though is an Israeli production called Zaytoun, which depicts an Israeli pilot being shot down over Sabra in 1982. After being captured, he convinces a young Palestinian boy to break him out of his cell and help him return to Israel, as they both have an interest in returning to that land. What’s immediately repugnant about this story is that the Palestinian side of the discourse is represented by a 12-year-old child. The only other Arabs are either militia-men, extras or a jolly, strangely naive, service driver. It’s meant to be a reconciliatory story but it never addresses the real divides inherent to the conflict and in some twisted way tries to equate the two characters’ struggles.

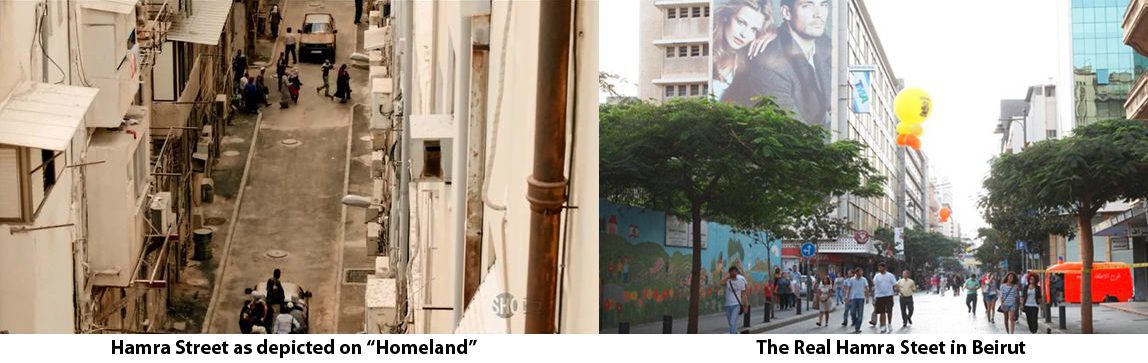

Another interesting example is Homeland, who’s depiction of Hamra I will include for illustration sake. To reiterate, it’s not a matter of accuracy, control of narrative is reality and by orientalizing the East they are creating the East in their collective minds. It, therefore, becomes a reality for them.

“Beirut”‘s Rewriting of History

Now, since the trailer includes the Israelis, “2000 years of revenge, vendetta and murder. Welcome to Beirut” can mean one of two things. Either that the Lebanese have been fighting each other since the Roman Empire, or that the conflict between Muslims and Jews has been going on since the Exodus. Both are completely flawed readings of history, the first makes all conflicts in the region today seem sporadic and ever-growing, and the second is a Zionist myth propagated for years, that Palestine is the ancestral home of all the world’s Jews — whilst of course ignoring that Zionism is a 20th century settler-colonial project.

If the Arabs can’t sort it out themselves, if “the monsters have taken over Beirut”, than it is ‘our’ duty to go in and save ‘them’ from themselves. This retelling of history is heavily informed by today’s power dynamics as is dictated by Orwell when he says: “Who controls the present controls the past. Who controls the past controls the future”. This is the ominous nature of creating and manipulating narratives.

My main concern about this film comes in the form of a question: Why now? Why make a film set in Beirut in 1982?

The only explanations I have, given the current political climate in the Middle East, is two-fold: there is clearly an interest in depicting Arabs as deserving of control and potentially could be beating the drums of war. After all, isn’t there immense growing pressure against Iran? Did Nikki Haley not stand in front of an Iranian-made missile and condemn Khamenei for ‘murdering’ his own people? And was 1982 not the birth of the resistance movement that saw Iranian involvement on Lebanese soil?

Yet, what I’m certain of is that this film will be harmful for the depiction of Arabs and ignores, and possibly glorifies the U.S and Israel’s involvement in the conflicts it covers. Since there is no comparable Arab film industry to counter it, it seems that their propaganda will prevail in the minds of many.

For the time being, we are stuck with writing indignant tweets and articles, but this is not to say it is all in vain, for as we take initiative to reclaim our narrative as a first step, it is not all lost. Indeed, we should remind ourselves of what Mahmoud Darwish once said: “We’ve heard the Trojan victim speak through the mouth of the Greek Euripides. As for me, I’m looking for the poet of Troy because Troy didn’t tell its story.”