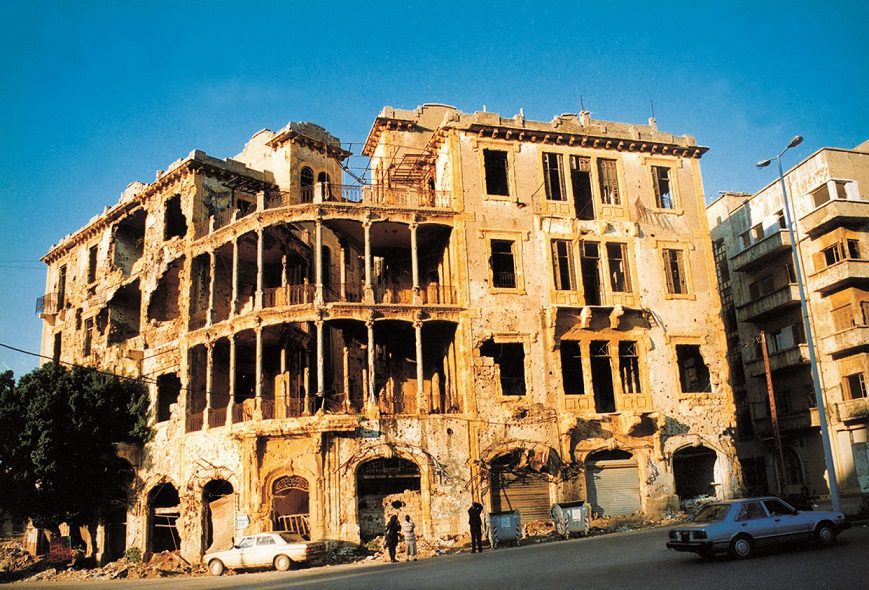

On a typical stroll through Beirut’s Sodeco area, any passerby that is not completely embroiled in the latest post on Instagram, could not possibly miss the historically rich and eye-grabbing, bullet-ridden yellow building. However, Beit Beirut is so much more than just a relic from Beirut’s past. It is the expanded temporal embodiment of Beirut’s experience as a city. It has survived so much and yet it still stands.

It is of common knowledge that the Lebanese Civil War had devastated much of old Beirut’s defining aspects and had perverted them into something else completely. A notable example is the Holiday Inn hotel in Ras Beirut, a place where numerous humanitarian violations had taken place.

Rest assured, this article is not another illustrative piece on the exhaustive architectural damage that had ravaged Beirut during the Civil War. It also isn’t a romanticized mythic tribute to life prior to the war and during the war. Rather, it seeks to highlight the possibility of change, reflection, and reconstruction within the context of a post-conflict society through the Beit Beirut initiative.

Beit Beirut, originally named the Barakat Building after the Barakat family, which commissioned the then famed architect Youssef Afandi Aftimos to design it in 1924. It consisted of a ground floor and another floor on top along with some spaces which were rented out as shops. In 1932, the building was expanded by a young architect named Fouad Kozah and included two more floors, which made up a total of eight apartments.

I was lucky enough to have been given a private tour by Mona Hallak– a director of the Neighborhood Initiative at the American University of Beirut, Architect, and heritage preservation activist. She was the person that saved the Barakat Building through her relentless drive to conserve her and Beirut’s “identity” when it was set to be demolished in 1997. Suffices to say, the narrative and the descriptive anecdotes that Ms. Hallak had outlined along with the experience of walking through the intrinsic building were enough to captivate any skeptic.

Ms. Hallak considers Beit Beirut to be the “avant-garde and pioneering” building of its time. It was built in such a way that gave it a spacious airiness and a visual axis and transparency. In short, the city, or more specifically the intersection between Damascus Street and Independence Street could be viewed from any angle throughout the building. Ms. Hallak pointed that this architectural transparency was a technique used by Aftimos, the original architect, to connect the building with the city and the city itself with the building.

A Building that Endures the Test of Time

Due to its architecturally designed and seamless panoramic view of the “Green Line” in the area, the then Barakat Building was an ideal location for any militia that sought a vantage point during the Civil War. In 1975, when the war had just started to ravage the city, the Barakat family moved out, taking all their belongings with them. Members of a Christian militia moved in shortly afterwards.

Just as the building had existed as a symbol of the bourgeois lifestyle, it was soon adjusted to fit into the context and circumstances of war. Sandbags and cement replaced lavish contemporary furniture, and peepholes were installed to house the infamous snipers that had once monopolized the intersection and the surrounding areas.

When Ms. Hallak had discovered it in 1994, the building’s yellow stone set against the blue sky were what mesmerized her and initiated her extended and passionate battle to preserve her heritage. Needless to say, the building was trashed, tarnished and covered in graffiti, but nevertheless, stood as a beautiful remnant of old Beirut. To her, it is more; it is a realistic and concrete representation of Beirut prior to the war and during the war.

Ms. Hallak also had several tangible encounters with the building’s residents. On the second floor of the building laid an apartment belonging to Dr. Najib Chemali. He was a dentist and his clinic was located in the house. Surprisingly, Dr. Chemali had left all of his belongings in the apartment. His apartment was jam-packed with a variety of items which included, but is not limited to: ads for shoes since the 1950s, practically every movie ever screened in Beirut, an infinite number of letters, and his dental equipment and chair. Ms. Hallak later discovered that he had passed in 1973. In addition, one of the stores that was located on the ground floor was a photography studio. Ms. Hallak found more than 11,000 negatives of different people.

Beit Beirut and Its Future

In 2008, Beit Beirut was restored and reconstructed. However, the modern additions clashed rather than complemented the building. Youssef Haidar, the architect that was assigned the task of rejuvenating Beit Beirut, assumed that a modern touch would be an ideal fit for the building. Unlike the additions in 1932 or even the adjustments during the civil war, the new additions actually served to destroy certain aspects of heritage throughout the building. It goes without saying that Ms. Hallak was sourly disappointed. This, however, did not discourage her insurmountable convictions towards Beit Beirut.

Today, Beit Beirut is being prepared to be launched as a museum. Ms. Hallak’s aim is to make it accessible to the public and to present it as more than just the “Museum of Memory”. She also wants to recreate Dr. Najib Chemali’s apartment so that the public can properly recognize and engage with his human experience in the then Barakat Building. Hallak also told Beirut Today that she hopes to have the public involved, by inviting them to search for the individuals seen in the photography studio’s 11,000 negatives. Moreover, the sandbags, concrete, sniper peepholes and bullet holes, the signature remains of the building during the civil war are still present and will also be on display.

It is not Ms. Hallak’s intention to be reminiscent of the past. On the contrary, she wants to put the past on display through the tangible experiences that had taken place in Beit Beirut. She hopes that Beit Beirut will be used as a tool to reflect on the past and to facilitate the healing process and the process of coming to terms with its atrocities.