The following article uses pseudonyms to protect the identities of those interviewed.

“I didn’t change. It was still me.” — Sarah, a 23-year-old queer student.

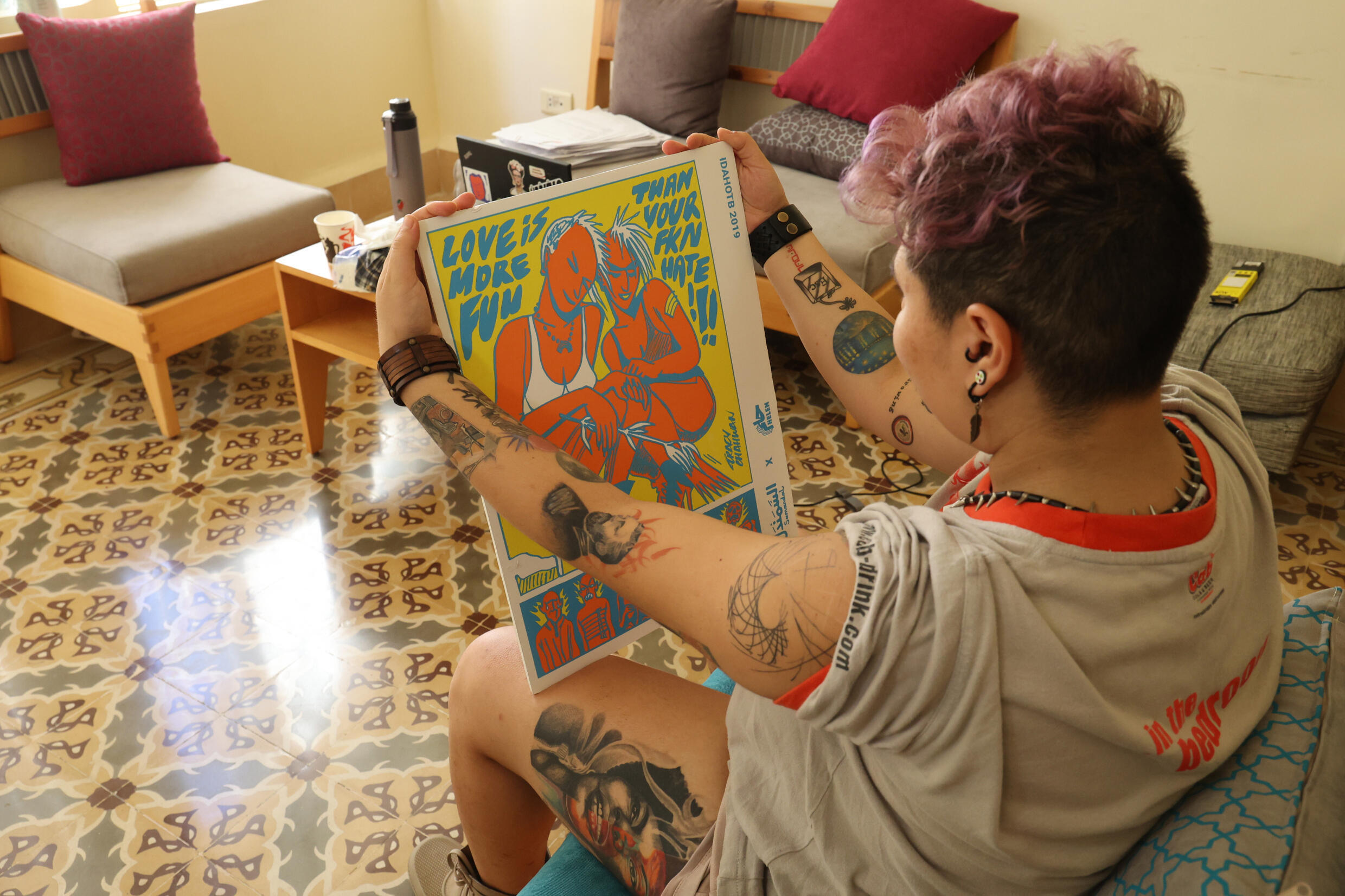

In Lebanon, where conservatism reigns supreme, a recent onslaught of transphobic and homophobic sentiments has endowed the queer community with a looming sense of fright and anxiousness.

LGBT-friendly public places, once a haven for these marginalized communities, now stand emptier, a solemn dejection hanging beneath the fluorescent lights of these spaces.

Queer people, who have historically been pushed to the sidelines, are now being pushed further into the shadows—in a systematic attempt to silence and oppress LGBT voices.

Across me sits Rhythm, a 19-year-old non-binary student. It is morning, the sunlight flutters in through the windowpanes as their hands rest clasped on the table before them, a youthful glow radiating from their cheeks.

“I’ve got an hour before my next class,” they inform me, smiling.

“I realized I don’t typically enjoy being referred to as ‘she’,” says Rhythm of the day they began to question their gender identity. “I don’t see myself as a girl.”

To Rhythm, such a revelation was incredibly liberating. Despite “the barriers” put in place by their family who “perceive [queerness] to be a trend, a sickness,” Rhythm found comfort in their identity.

Narrating the moment they realized their true self, they note “There’s no words [to describe it]. That’s me.”

Yet, notwithstanding the solace uncovered in their gender expression, the road to self-fulfillment remains treacherous for Rhythm. Shy and introverted, they feel unable to escape the questioning gazes of strangers, stating “I am constantly perceived.”

According to them, queer individuals are continuously obligated to justify their mere existence, being bombarded with incessant interrogations.

Chuckling, Rhythm quips “I’ve had people come up to me to me on motorcycles and ask ‘Are you a boy or a girl?’’

Of the countless queer youth who have uprooted themselves is Sarah—a 23-year-old Lebanese woman who recently moved to Europe to pursue higher studies. Speaking of her experience as a queer woman in a rural Lebanese town, Sarah interestingly notes that she did not feel alienated.

“I felt like I had a different hair color,” she adds. “I didn’t want it to be a big deal. I didn’t change. I was still me.”

This changed, however, when Sarah came of age and “started finding out about places that other queer people frequented.” Having lived outside of Beirut for most of her life, Sarah laments the inaccessibility of queer spaces beyond the limits of the capital.

This centralization of safe spaces in Beirut, according to Sarah, makes it difficult for many within the LGBT community—especially those who are younger or do not have access to the financial frameworks that allow them to make frequent trips to the city.

Regardless, Sarah notes that she is “very grateful for the fact that [queer individuals] have these spaces, as scarce as they may be, where [they] can go and sit and breathe easier.”

Despite the relative rarity of these spaces, they have recently come under fire by local extremist groups.

This premeditated targeting of queer spaces disallows them from finding safety in a community that comprehends and reflects their individual struggles.

In such a community where familial bonds are often severed, one’s ‘chosen family’ is, alas, one’s only system of support. In reflecting on these spaces, Sarah notes “It is very important to maintain the spaces we have fought so hard to establish.”

Qid, a 36-year-old Lebanese transgender man, sympathizes with this statement.

“We went from pushing for better legal [frameworks] to needing to maintain what we have,” he said.

This notion of ‘maintenance’ was reflected upon by all three of the interviewees. It is apparent that, far from the picture painted by conservative outlets of the queer community supposedly “taking over” public spaces, queer individuals are struggling to merely survive—often incapable of keeping themselves and loved ones safe.

“For some people, backing down is not even an option, it would mean giving up on who they really are,” says Qid.

Indeed, many members of the community are now tasked with the daunting responsibility of choosing to either be themselves or forgo a part of their identity, forcing themselves into a mold that they do not fit.

Despite the lingering sense of despondency, Sarah notes that what keeps her spirits up in these troubling days is “that these [queer] spaces did not close—they opened back up.”

Smiling, she adds “Nothing as silly as fear will get us to stop existing.”

Similarly, Qid shares words of encouragement for the youth in the queer community. Regardless of the difficulty of surviving one’s teenage years, he notes that with time “it gets easier with yourself.”

This current worrisome climate, though perturbing, is fleeting. Qid explains “For society to change, you need multiple things, including time.”

Queer people, according to Qid, are now visible in places they did not have access to before.

“But that’s good,” he adds, “people are learning through them.”

“Ten, twenty years ago, the [current] multi-generations of queer people did not exist,” Qid explains. “Before, it was much lonelier. There wasn’t space for people to support each other.”

“The community is in a very different place,” Qid explains, “the hubs of support are very different. There are more allies that speak out than before. That didn’t exist before. This is a success in itself.“

Yet, despite this increase in ally-ship, Rhythm feels disheartened, asking allies to “speak up.” In a similar vein, Qid states, “[Allies] need to be better aware of what is the discourse, what is happening, and how to respond.”

Reflecting on the recent violence, he remarks “This is part of the progression. [Homophobes] are saying: I see you. You are trying to be visible and change the societal view of queer communities. I see you and I want to hurt you.”

Regardless of the hostile environment surrounding discussions about queer people, what matters is that they occur. People may look at queer individuals with hateful eyes, but, perhaps for the first time ever, they are looking.