Lebanon’s Ministry of Energy and Water and local organizations have begun to clean the course of Al-Jawz River in Batroun, removing the accumulated dirt and dust on its route since it dried up at the end of June as it regularly does.

Yet these preparations are not enough to allow us to benefit from the river, as it is heavily polluted despite being a historic touristic site that remains under ministry protection.

Its spring and mouth

The river has two sources above the Tannourine area: the Dalli spring in the east, and the Fateh spring in the south. The two sources meet to create the main river that passes below the Tannourine Cedar Reserve, its mouth being in the Mediterranean Sea near Batroun.

The river is around 38 kilometers long and 196 kilometers squared in width. It provides drinking and irrigation water to Batroun, and its pathway is characterized by dense forest wealth. The river serves multiple sectors, aiding water mills, irrigated fields, power generators, cafes, and restaurants, in addition to domestic use in households across Batroun and its surrounding areas.

Annual measurements of the seasonal Al-Jawz River show that the river completely dries out from the Kaftoun Valley and up until its mouth during summer, starting in May during years of water scarcity or in June during years when it rains more.

On July 28, 2022, Lebanon endorsed a historical resolution put forth by the United Nations General Assembly that affirmed the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a universal human right.

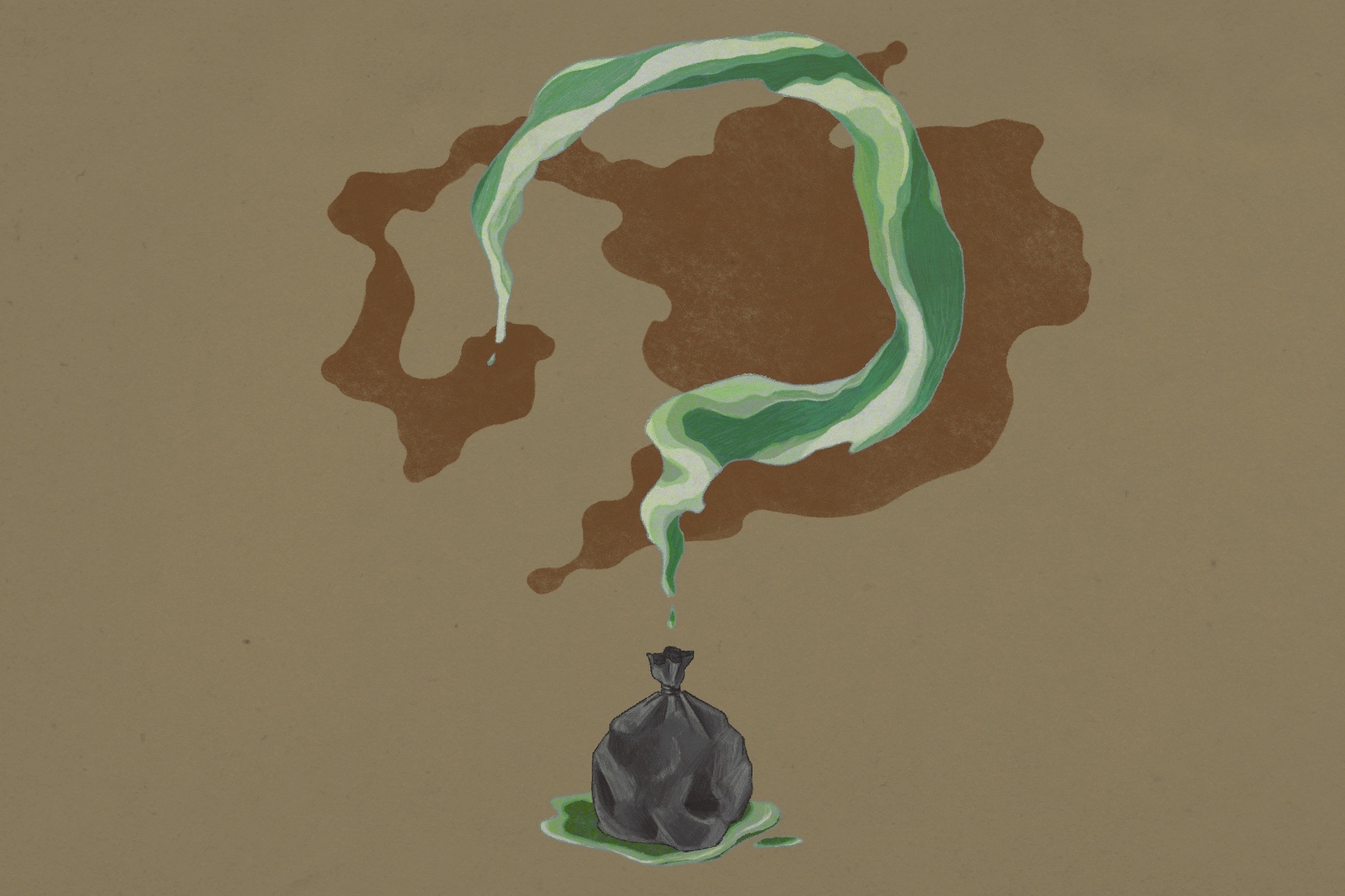

But Al-Jawz river’s course is threatened by wastewater, industrial waste, quarries, and the balaa and Mseilha dams, despite it being a vital artery to the villages and towns surrounding it in Batroun and Koura.

Studying pollution in the river

In 2019, the Office of Geological and Hydrogeological Studies conducted a study under the supervision of Dr. Samir Zaatiti on the pollution of the Dalli spring, which flows into Al-Jawz River and covers Tannourine, Douma, Kfour El-Arabi, Kfarhelda, and the eastern hills of Batroun in the North Lebanon governorate.

The study was officially requested by the North’s Environmental Prosecutor, Ghassan Bassil. Its aim was to find ways to minimize the problem of pollution and find solutions to prevent the pollution from reaching the spring.

According to the study, rain is the main and only source of water that feeds into various categories of rocks. The average annual amount of rainwater in the region is estimated to be between 1,100 and 1,250 millimeters annually, a relatively high rate. A chunk of this rainwater, as well as the snow accumulated in the winter, is stored as groundwater.

The river is classified as a protected natural area under the Ministry of Environment, as per Law 22 of 24/2/1998. The second clause of this law states that the entire area, in addition to its surrounding 500 meters, must be protected. Meanwhile, its third clause states that the ministry is the only authority capable of authorizing work permits in this area, as it sees fit.

The reasons behind the pollution

“The study began by documenting the liquid materials and the rejects of olive oil, which is the most obvious pollutant because its black color stains the water,” Dr. Zaatiti told Beirut Today.

“It’s especially present during the olive season, with several types of organic and microbially harmless waste appearing,” he added. “However, its accumulation on the surface and its presence in the soil, running water, and groundwater has harmful effects.”

He also clarified that organic matter, in its natural state, is not harmful, but its presence in bodies of water subjects them to chemical and bacterial interactions that cause it to become a pollutant.

After explaining in length about the geological and political nature of the area and the presence of political parties in it, Zaatiti said that the residents of the villages surrounding Al-Jawz River use the river’s water after filtering it. They put chlorine in it to kill any present harmful substances prior to drinking it.

Dr. Zaatiti listed the various pollutants, accusing the nearby Tannourine el Tahta Hospital of disposing of its garbage by way of the river. He also accused nearby pig, cow and chicken farms of similarly disposing of their waste, alongside greenhouses disposing of their fertilizers and bug repellants in Al-Jawz River.

He likened Al-Jawz river as a microcosm of the Litani River.

He then clarified that organic material, such as the rejects of olive oil, does not actually pollute the river. Rather, the remnants of fertilizers and insecticides, household waste, the waste of the Tannourine hospital, in addition to some construction work being done on the river’s pathways, are the main pollutants of the river.

On Syrian refugees camps

When asked about rumors regarding pollution being caused by nearby Syrian refugee camps, Zaatiti was confused.

“How can Syrian refugees pollute the river? They do not have chemical waste or insecticides to dispose of,” he said. “Even organic and human waste is not considered a pollutant, because everything organic goes back to nature.”

The doctor warned against plastic and chemical material, inorganic material that pollutes nature.

“Dinosaurs lived on this planet for 175 million years, ruling the world before they became extinct, but they never once polluted it by leaving plastic, glass, or any other kind of unnatural pollutant,” he added, jokingly. “Humans started generating energy in the 18th century using coal and hazardous materials that accumulate day after day, irreversibly polluting the planet.”

It seems that laws and legislation will not prevent encroachment on Al-Jawz River and its pollution, with the need to rule with an iron fist when it comes to environmental protection becoming more clear than ever.