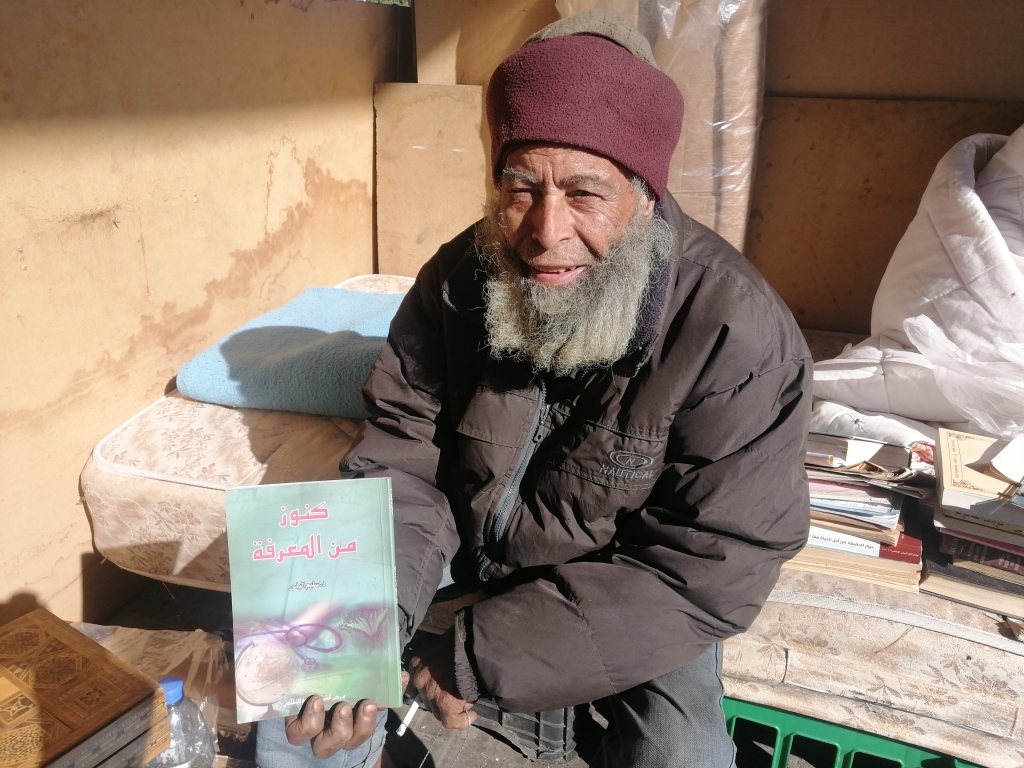

“Pick out the book you like for free, and congratulations,” bookseller Mohamed Maghrabi would say to anyone who visited him under the steel bridge in Beirut’s Jisr El Fiat, Corniche El Nahr.

Sorted piles of books donated by “good people” lined up Maghrabi’s “bookstore.” Others were scattered around, and in between the two were books being sorted to put up on display after being bought from Souk al-Ahad or the market in Sabra.

Maghrabi lives off donations, selling piles of books to those who want them and giving away others to those who can’t pay for them.

His workplace doubled as his home, come rain or shine, before it was burned down earlier today for unknown reasons. Maghrabi is physically unhurt.

A wood-burning stove and a mattress for sleeping stood within walls made of wood, cardboard, and books. Among his few scattered belongings was a light brown suit hanging at the entrance to be used when necessary, and a few fruits to offer those who visit him.

Maghrabi, who is in his 80s, thinks each book is special. He talks passionately about some of them, especially those written by influential Egyptian writer Taha Hussein.

“They’re all beautiful,” he told Beirut Today days ago, adding that gripping ideas may or may not be entrenched in the minds of readers after they browse through books. It’s a matter of opinion.

A blessed patch

“Lebanon is a blessed batch,” said the bookseller in an Egyptian accent. “Since ancient times, people have sought out this patch and failed battles have taken place to control it.”

Maghrabi talked about politics and sociology, mentioning that he studied civil engineering and modern architecture back in Egypt. He kept up with the news through an old radio that rests by his mattress.

His story began when he was imprisoned for a crime he says he did not commit. Maghrabi was accused of using forged money, but says he did not know it was forged and that he obtained it as a commission for being an intermediary between a seller and a buyer of a truck.

Time in prison

Maghrabi told Beirut Today that he spent a year and two months in a cell collecting books, “healing them” (patching up their tears), and reading. When he asked about his crime and sentencing, no one would listen.

The bookseller said he was peaceful and friendly in prison, and that his main interest was reading—even impressing the warden along the way.

“I was imprisoned on the basis of a file consisting of a blank sheet of paper, without any charges brought up against me,” said Maghrabi. He paused for a moment. “If it weren’t for the former Minister of Interior, Raya El Hassan, I wouldn’t have been released from Roumieh prison to this day.”

He explained that El Hassan visited the central prison when she was minister and asked authorities to reconsider the files of detainees.

“When a hearing was scheduled for me, the judge was surprised to find it empty and to see that no charges were brought against me,” he said. “I came out of prison innocent, and I filed a complaint against the person who wronged me but its fate is still unknown.”

Maghrabi repeated one pained phrase, “I got out of prison and wished I hadn’t.”

After being released, he made his way to Sin El Fil only to find that his house near Mirna El Chalouhi Center had been flattened and razed to the ground. “It was the shock of my life.”

A great shock

“I walked in the streets completely shocked. I had nothing, and I had the terrible feeling of not knowing what to do,” he said. “I was exhausted by the time I arrived at this spot, so I slept on cardboard and that’s how my new life as a homeless man began.”

Maghrabi began to collect books, and accepted his first donation in the form of an encyclopedia from a stranger.

Lebanon’s economic crisis has made homelessness an everyday phenomenon in the country, particularly in light of the absence of a functional state and social support systems. Around 80 percent of the population has sunk into poverty, according to the UN.

While local and international organizations scramble to limit it and ensure the homeless have a dignified life, Maghrabi refuses to turn to them for aid. He insists on returning to his home only, not on living in a nursing home or in someone else’s house.

The Minister of Culture’s visit

Lebanon’s Minister of Culture, Judge Mohammad El-Mortada, visited Maghrabi on January 13. The minister’s visit lasted an hour, during which he heard Maghrabi’s story and donated a collection of books to him.

“I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Mohamed Maghrabi, who practices culture in its best manifestations even in the grimmest of public and personal circumstances. Respect and appreciation,” wrote the minister.

Maghrabi told Beirut Today that the minister’s visit to his home brought along an interesting conversation. He said nothing was promised to him but described El-Mortada as humble and courteous.

“I explained my story to him and it captured his interest,” said Maghrabi. “I’ll never forget this visit. It’s engraved in my heart.”

The bookseller, who said he was born in the Mazraa region, had big ambitions for the future. He’d like to launch a maritime transport project from the north, passing through Beirut, to the south of Lebanon using a boat that runs on batteries and solar energy. He’d also like to establish an iron and steel plant.

But his dreams may have to be put on hold. Can he rebuild his bookstore—and home—to what it was before the fire, and spread culture among everyday people?