When Queen Rania of Jordan met Pope Leo XIV in October 2025 and asked on camera whether it was safe for him to travel to Lebanon for his first apostolic journey abroad, he politely but firmly replied: “Well, we’re going.” The clip of this exchange went viral, spawning stylized fan edits of the Pope on TikTok.

And indeed, he went. Triumphantly so, for that matter: from November 30 to December 2, Pope Leo visited Lebanon, where he was welcomed with thunderous applause, cheers and the country’s hospitality on full display.

However, when considering Lebanon’s ornate and elaborate arrangements for this visit, an English idiom comes to mind: all that glitters is not gold. Beyond the official narrative of peace and interreligious dialogue, another discourse emerged among Lebanese people during this papal visit. Many social media users suggested that the sudden infrastructure repairs, the promises of 5G and the availability of fully running electricity may have been intended to project a favorable image of Lebanon to the Pope.

An important question thus arises: did the Lebanese public view the official arrangements for Pope Leo’s visit as the foundation for a meaningful national and spiritual moment, or as a reminder of the absence of essential services?

The Pope’s visit as an expression of collective effervescence

Hailed as exceptional and historic, Pope Leo’s visit to Lebanon can be understood as a collective ritual action through a Durkheimian lens: a ceremonial event structured around sacred symbols which ushered in a heightened sense of social belonging.

Known as the father of sociology, Émile Durkheim emphasized the social role of religion in sustaining a collective conscience. In Lebanon, a country made up of both Muslim and Christian populations, Pope Leo’s visit attested to this role within the Maronite Catholic population. Appreciated by Muslim communities, including their religious and political leaders, the visit also symbolically highlighted the national emphasis on interreligious coexistence. The recurrent references to Lebanon as “the land of the sacred cedar”, used notably by the Lebanese air force to welcome the Vatican’s planes on the first day of the visit, also attest to this national imagery.

The Pope’s arrival set in motion the production of sacred collective representations among Maronite Catholics and other Christian communities, as well as national, secular symbols. On his way to the presidential palace, Pope Leo was welcomed by raucous crowds and large groups of Lebanese musicians and dancers performing Dabké, a traditional folk dance. He planted an olive tree in the presence of Christian and Muslim religious leaders to promote national unity. He also became the first Pope to visit the tomb of Saint Charbel, a Lebanese Maronite hermit venerated for miraculous healings. He also prayed at the site of the Beirut explosion that claimed the lives of 235 people in 2020, marking a moment of solidarity with the Lebanese people.

The Durkheimian concept of collective effervescence, achieved through the sacred rituals of the Pope’s visit, also extended to social media to a certain degree. Facebook reels of his Mass circulated widely among Lebanese circles, and many users’ comments took the form of ritualistic, religious affirmations such as prayer emojis and the words “Amen” and “Peace of Christ” in Arabic.

Blessed are the peacemakers!

With the Bible verse “Blessed are the peacemakers” constituting the slogan of his visit, Pope Leo made peace his key focus across his speeches, prayers and social media posts. Not to mention that he invoked peace in Lebanese Arabic, English and French, reflecting the linguistic trifecta that typically characterizes Lebanese speakers.

Not only was peace the central theme of Pope Leo’s visit, it also prevailed in Lebanese social media conversations. A quantitative analysis of social media posts in Lebanon from November 29 (the day before Pope Leo’s arrival) to December 3 (the day following his departure) confirms this. During this time frame, over 18.9K posts were created in Lebanon across Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, Reddit and Bluesky. Words linked to the vocabulary of peace emerge as the most common keywords found across these posts: السلام (“peace” in Arabic), سلام (“peace” without the definitive article), #بابا_السلام (“#Pope_of_Peace”), #لبنان_يريد_السلام (“#Lebanon_wants_peace”). These keywords appeared in over 21% of total posts during the Pope’s visit.

Word cloud of the top 120 keywords appearing in social media posts (Facebook, X, Instagram, Reddit, YouTube and Bluesky) from November 29 to December 3.

Source: Talkwalker

Nawaf Salam, Lebanon’s current Prime Minister who is largely viewed as a reformist, emphasized peace on social media. Salam’s post on X about his audience with the Pope features the word “peace” three times, stating that this visit represents a gesture of solidarity with all Lebanese people, particularly the youth and “their right to peace.”

Moreover, the posts receiving the highest engagement across social media came from the mainstream media outlets LBCI News, Al Jadeed and Annahar. LBCI (Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation International) dominated the social media conversation with constant updates about the Pope’s visit. LBCI’s hashtags (#LBCINews, #LBCILebanon, #LBCIVideos, #LBCILebanonNews and #BreakingNews) all appeared in approximately 30% of all posts.

This mainstream coverage helped crystallize the way the visit was framed by authorities to amplify the Pope’s calls for peace.

All that glitters isn’t gold

Despite the ceremonial grandeur of this visit, not all citizens were impressed; many voiced skepticism and anger, viewing it as a superficial display that swept the nation’s socioeconomic woes under the rug (or, in this case, red carpet).

On Facebook, which remains a widely used social media network in Lebanon, users expressed their socioeconomic grievances in long posts.

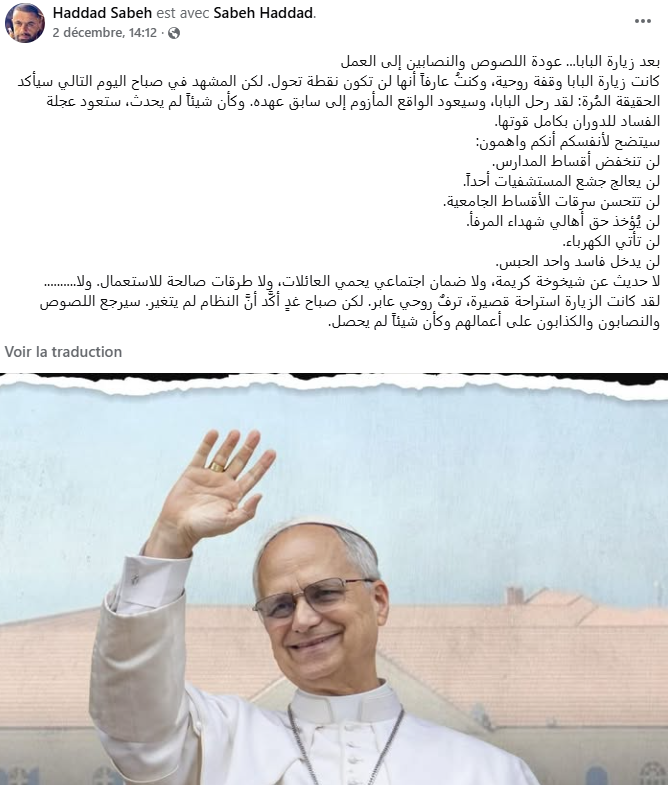

Haddad Sabeh, a Facebook content creator with 9.7K followers, is one of them. In a Facebook post written after the Pope’s departure, he stated that the visit only provided a temporary spiritual pause and would not affect Lebanon’s ongoing socioeconomic challenges. He wrote that “corruption, greed, and failures in schools, hospitals, universities and public services” would persist, and that, in his view, the establishment, described by him as “thieves, fraudsters, and liars”, would return to business as usual.

Another content creator called Chafic Habib also voiced his opinion: he described the logistics of the visit as “inevitable channels for theft and waste at the expense of people and their daily suffering,” adding that “no visit from any public figure will change this reality unless these crises are addressed directly.”

Other Facebook users echoed this sentiment. One wrote that although “the Pope’s presence was a symbol of peace and love,” he suggested that political and religious authorities were trying to present a “polished image of Lebanon that conceals the country’s deep poverty.” Another user argued that “the Lebanese deserve a real state.”

Lebanon’s younger generation also expressed these views in a different format: not through lengthy Facebook posts, but through short comedy videos on TikTok. Content creator Wassim Hassoun joked in a viral video that if the Pope’s visits bring road repairs and steady electricity, “he should come every day.”

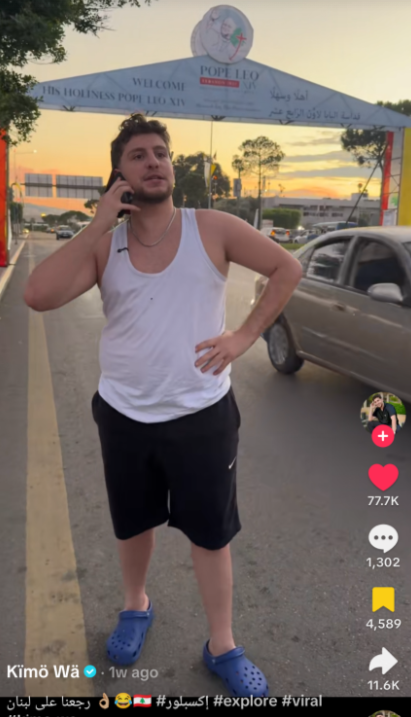

Two other content creators, Kimo Wa (3.2 million followers on TikTok) and Samer Moumneh (128.3K followers), posted viral comedy skits reflecting this sentiment after the Pope’s departure. Both skits, viewed over 1.7M and 300K times respectively, follow a similar structure: each comedian is shown at the Lebanese airport nicely dressed in formal attire and politely bidding farewell to the Pope. They then proceed to remove their respective suits to adorn a white undershirt and slippers, symbolically showing the return to normalcy in Lebanon, or rather normalized dysfunction.

Kimo Wa’s character specifically says in Lebanese Arabic: “Let’s rid ourselves of ‘Lebanon’ and return to ‘Lebnen’!” (Lebnen being the Lebanese pronunciation of Loubnan, the Arabic word for Lebanon). Interestingly, this linguistic dichotomy highlights a broader trend on TikTok that carefully distinguishes the curated, idealized vision of “Lebanon” and the authentically chaotic reality of “Lebnen.” Kimo’s character, now donning a white undershirt, shorts and Blue crocs, is seen talking to his father on the phone over issues at home that Lebanese people know all too well: the electricity and the backup generator are out and the water is no longer running. Even the WiFi isn’t working.

Samer’s character, who also trades his formal suit for a white undershirt, urges everyone to “break the roads again and downgrade 5G connectivity to 3G” now that the Pope is gone.

Both videos therefore use symbolic markers to show the dissonance between the polished “Lebanon” shown to the Pope and the lived reality of “Lebnen” with its socioeconomic challenges.

From a Durkheimian perspective, the distinction between the sacred and the profane is therefore challenged when it comes to building social belonging in Lebanon. On the one hand, the sacred, which manifested through religious rituals during the Pope’s visit, reinforced social cohesion, particularly among Maronite Catholics who engaged in these practices, as well as Muslims who welcomed the Pope’s focus on national unity.

On the other hand, it can be argued that the profane, referring to the mundane aspects of everyday life, also created solidarity among Lebanese people. For example, the viral TikToks above precisely reflect collective engagement with shared socioeconomic frustrations, where users laughed and commiserated over common everyday problems. In this regard, it seems that the collective representations of the profane on social media, meaning videos that emphasize everyday struggles and dysfunctions, mirrored some functions of the sacred by allowing users to bond over similar problems.

Durkheim’s question of the conditions for social order in society becomes more nuanced when said society is perceived as disorderly. Lebanese people, regardless of their religious identity, are bound together through their shared experience of these everyday struggles.

Lebanese social commentary around the Pope’s visit ultimately shows us one thing: yes, Lebanon wants peace. But Lebanon (or should I say Lebnen?) also wants running electricity, decent infrastructure and affordable state services. And the Lebanese demand that the establishment provide real these provisions all year-round, not just when the Pope comes to town.