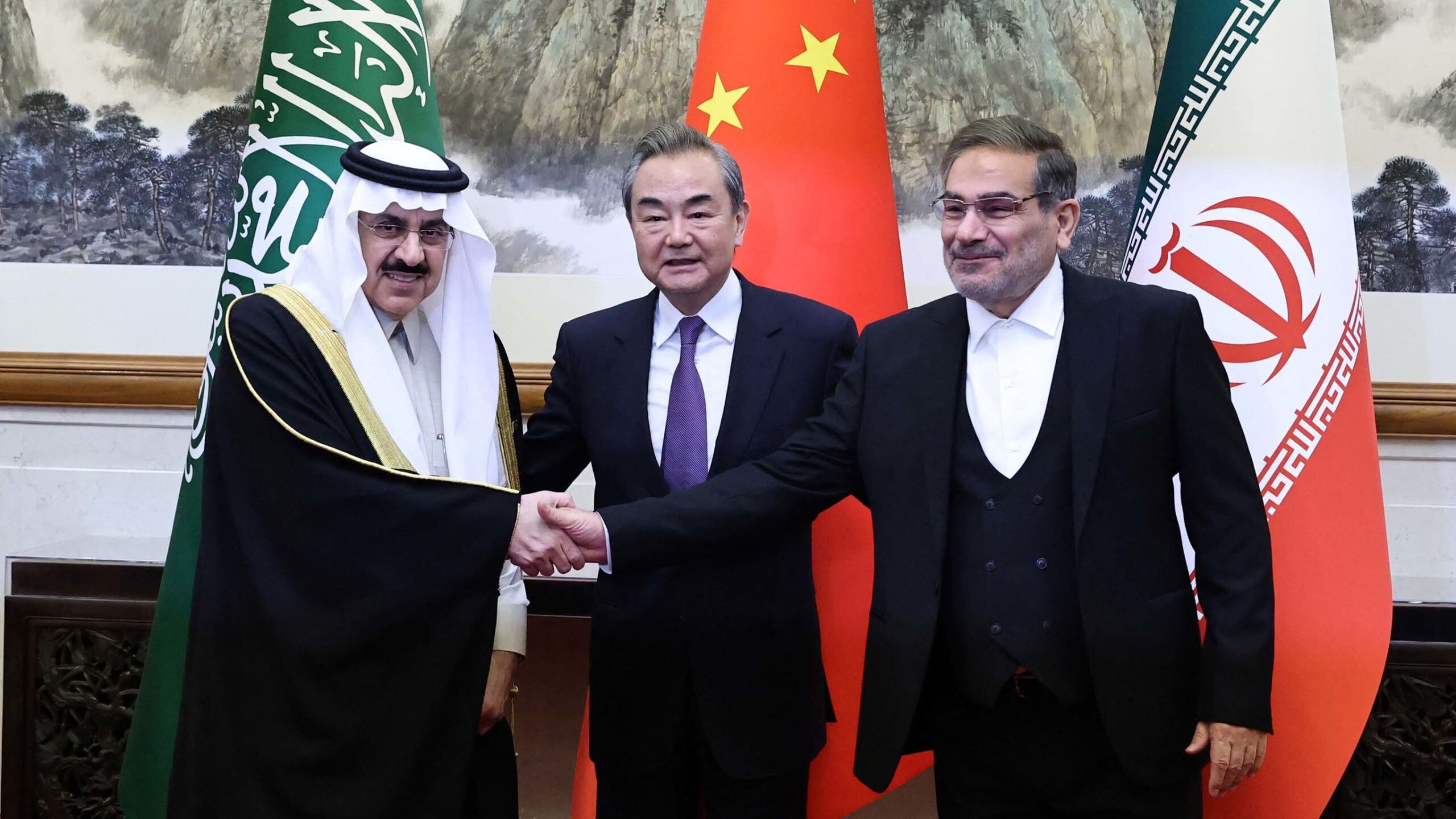

Iran and Saudi Arabia took the world by surprise on March 10 when they announced from Beijing an agreement to resume diplomatic relations after an 8-year hiatus. This diplomatic breakthrough is expected to ease tensions in the region, which has long been the theatre where Saudi – Iranian rivalry has played out.

But its impact on the economic and political situation in Lebanon is still shrouded in uncertainty. The Yemen war, a costly and protracted conflict, is first on Saudi Arabia’s agenda, and will serve as a testing ground for its deal with Iran. Trailing further behind on the Kingdom’s priorities is Lebanon.

Observers say it will be a long time before the cash-strapped country feels the impact of the Saudi – Iranian rapprochement, presaging the prolongation of a political deadlock that has only exacerbated the situation in a country on the edge of collapse.

No president in sight

Lebanon is reeling from a presidential vacuum that has entered its sixth month as parties fail to reach a consensus over a presidential candidate. Although the deal is likely to help alleviate simmering sectarian tensions, and push for dialogue between rival parties, analysts recommend cautious optimism.

“Do not expect miracles from the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement,” says Hilal Kashan, a professor of political science at the American University of Beirut.

“Electing a president and forming a cabinet is always problematic in Lebanon […] It has been a month since Iran and Saudi Arabia decided to restore their diplomatic relations, and something has yet to happen in Lebanon to point toward a settlement.”

Major political decision-making and coexistence in Lebanon are commonly the product of international and regional mediation, and compromise between competing factions – an often-lengthy process. Before the election of former president Michel Aoun in 2016, Lebanon’s presidency was vacant for almost two and a half years as parliament failed to reach a quorum to elect a head of state.

“It’s not very clear how that [presidential deadlock] will be resolved quickly” says Mohanad Hage Ali, senior fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center, adding “I think it is more likely to happen now than it was before the deal, but it needs more work and time.”

The agreement drew a slew of interpretations from across the Lebanese political landscape. Pro-Hezbollah commentators lauded it as a win that would see Saudi Arabian concessions on the presidential candidate in exchange for Iranian concessions in Yemen. Conversely, anti-Hezbollah groups said it signaled Iran’s growing need to come out of isolation and would usher in the election of a ‘sovereignty’ candidate.

Joseph Bahout, director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs in Beirut, says there are no signs of things heading in either direction.

“What is sure now is that the presidency […] is postponed because all parties and players, even external players like France and the US […] will wait and see how this deal will translate on the ground and will reverberate in Lebanon,” Bahout said at a Middle East Council webinar.

Foreign influence: A thorny issue

The Saudi Iranian agreement affirms the two countries’ “respect for the sovereignty of states and the non-interference in internal affairs of states”.

This clause struck a chord in Lebanese political circles hostile to Iran-backed Hezbollah. The powerful groups’ growing clout in the country and its support for the Houthis in Yemen are widely seen as the main reasons behind the souring of relations between Lebanon and Saudi Arabia in past years.

A long-time friend and major importer of Lebanese goods, the Kingdom revoked its ambassador and banned all imports from Lebanon in October 2021, in response to a Lebanese minister’s criticism of Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen. Saudi Arabia has since renewed ties with Lebanon, but its influence in the country has waned in recent years.

Its traditional Sunni ally, former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, has quit politics, and the Kingdom has increasingly championed the West’s stance on making financial aid to Lebanon contingent upon the enactment of reforms.

Hage Ali says he would take the agreement’s provisions “with a pinch of salt”. Echoing the West’s skepticism towards Iran’s commitment to the deal, he does not see the Islamic Republic dismantling its network of non-state actors in the region, including Hezbollah

Kashan is of the same opinion: “Hezbollah will not disarm, no matter what, and I do not believe Iran will change its regional policies to restore diplomatic ties with Riyadh,” he says.

Kassim Kassir, a journalist and analyst close to Hezbollah, interprets this clause as meaning “no direct interference”. He suggests that it does not concern Iran’s influence in Lebanon which he says “is indirectly linked to the role of Hezbollah, a Lebanese party with a large Lebanese following.”

Lingering political reform

The wave of optimism that has swept the region following the deal’s announcement, including in Lebanon, is premature, though a slow but steady reconciliation in the next few months is more probable.

Last month, Iran and Saudi Arabia’s foreign ministers discussed in Beijing the reopening of diplomatic missions and the resumption of direct flights. In Yemen, peace talks between Houthis and Saudi Arabia have made significant progress and hundreds of prisoners of war from both sides were released.

While there are reasons for optimism, many challenges still lie ahead. Along with Iran’s nuclear program, one of the thornier issues that they will need to tackle is the Islamic Republic’s growing network of non-state actors in the region.

Whatever the outcome of the agreement is, the political vacuum has crippled Lebanon’s executive once again and Hezbollah’s grip in the country will not loosen anytime soon. Even if this agreement paves the way for a détente between opposing parties, it cannot solve the country’s problems which Ali Hashem, senior Al Jazeera correspondent, says are deep-rooted: “It’s the mentality, the politics, the corruption. All these factors really prevent any solution in Lebanon […] that [deal] won’t change the situation of the failed state, the banana republic.”