Many complain about how bad the Lebanese passport is as a travel document and how humiliating the process of obtaining visas to the European Union, Canada, the United States and elsewhere is.

We often forget that despite the many hurdles on our tiny territory and our bodies, we are a cultured, multilingual and well-travelled people. These attributes could arguably be the greatest honour to any population. Most of the world’s inhabitants have never left their home city, let alone their country.

This “digital nomad/I want to experience the world/go on a journey of self-discovery” vibe is quite recent, even in Europe. There is a disinterest in travelling (especially to unconventional places…) but although in financial difficulty and suffering from many legal and administrative hurdles, the Lebanese dream of going elsewhere—whether on vacation to Antalya or immigration to Montreal.

Most would shrug off any mention of the Phoenicians, but does even the slightest link to them have anything to do with our contemporary desire to explore and travel to the unknown?

Our grand diaspora is the product of the Great Famine in Mount Lebanon of 1915-17. People left their miserable lives for the United States, Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. They built new and prosperous communities. Spoiler alert: Lebanon remained and eventually prospered.

Many new-comers settled in Beirut and elsewhere and adopted a Lebanese identity. This is the natural course of the global history of migration. Not to mention that being bilingual has scientifically been proven to be beneficial to brain development and overall health only recently. The Lebanese have been bilingual—if not multilingual—for centuries.

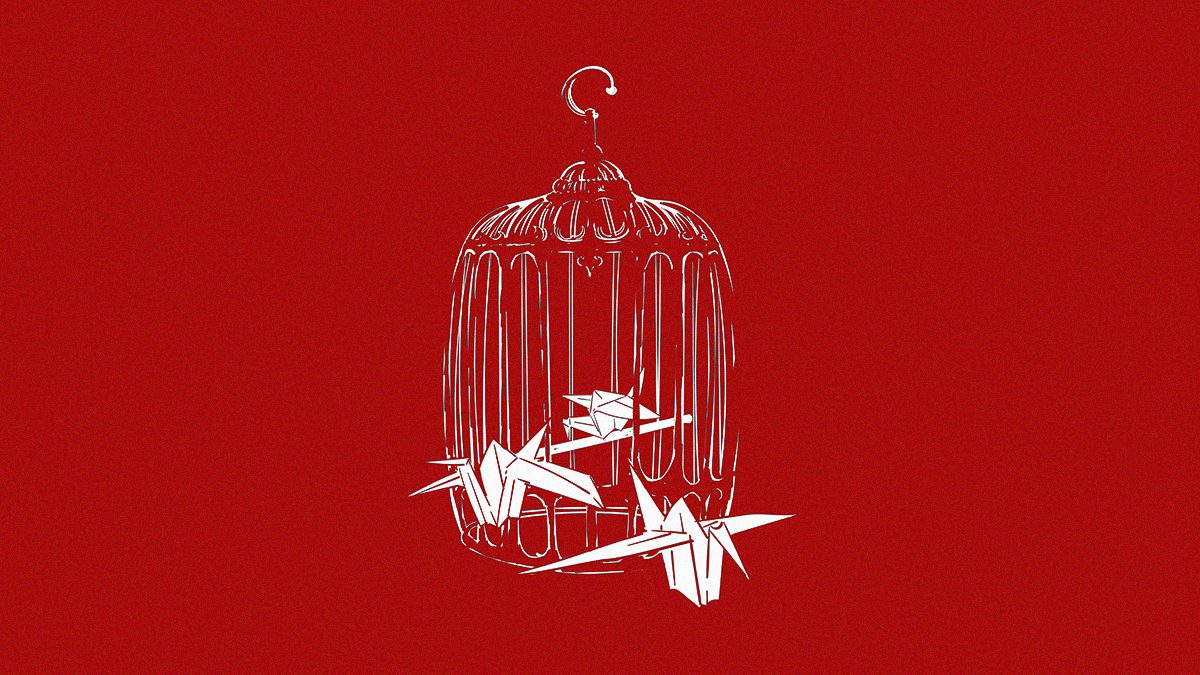

Modern political geography denies us our freedom to move. Coined by Stéphane Rosière & Reece Jones in their article “Teichopolitics: Re-considering Globalisation Through the Role of Walls and Fences“, teichopolitics is defined as “the politics of building barriers on borders for various security purposes.”

In Lebanon’s case, it refers to our closed and heavily securitized southern border with Israel, the security concerns with Syria on our northern and eastern border (not to mention the corrupt Syrian border guards) and our very inability to utilise the very resource our ancient ancestors used: the sea.

We can’t take a ferry to Limassol anymore. Our once prosperous port in Beirut is no more and international flights to and from the only airport in the country are getting cancelled due to the dire economic and financial situation. Our infrastructure is crumbling and fuel prices are rising. Power politics coupled with nationalism and white supremacy deny us our legal right to move freely.

In this case, we can look at Michel Foucault’s Biopolitics, and subsequently Biopower, which refers to the very subjugation of our individual bodies and those of our community to the prohibition of the very natural phenomenon of movement.

In fact, freedom of movement is enshrined in the International Declaration of Human Rights and the United Nations charter. Mobility has always been part of our global human history but unfortunately the advent of the modern state (and nation-state) punished our “third-world” bodies to be confined to a given territory—the small Republic of Lebanon in this case.

I would argue that the many long lines at the General Security and the rise in applications for a passport is not to be taken as a sign of betrayal of Lebanon, but the natural reaction of a human being to move elsewhere when the land on which they were born and raised becomes a source of misfortune and despair.

Nationalism and national identity are modern phenomena. When basic necessities are non-existent, it is okay—if not necessary—to move elsewhere to a place that offers food, shelter and the necessary safety for our bodies. Need not complain or fight the system; France and Canada are but 2 modern states out of 194 internationally recognized ones.

Competent, educated and worldly Lebanese passport holders must look beyond Lebanon. In fact, it would be a dishonour to our history and humanity if we don’t. Our bodies deserve better than a piece of land we were forcefully taught to love, cherish and blindly worship. We might have a less fortunate travel document but, again, our worldliness is more valuable than any white person’s EU passport.

Go, leave and do not look back. Lebanon will be fine.