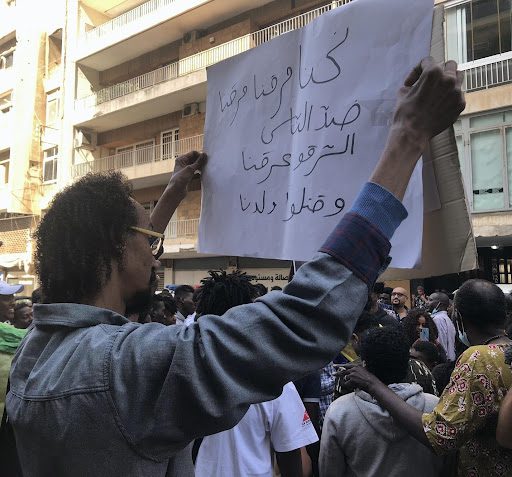

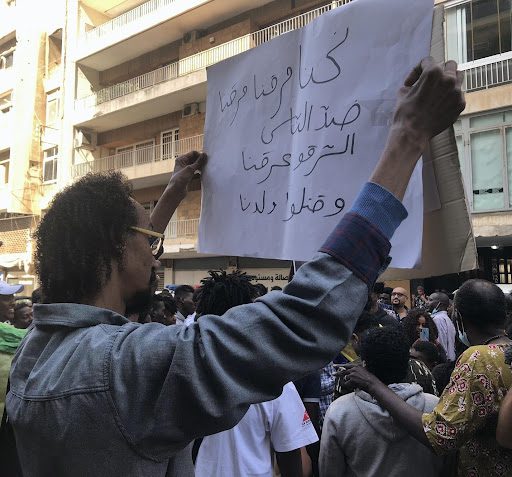

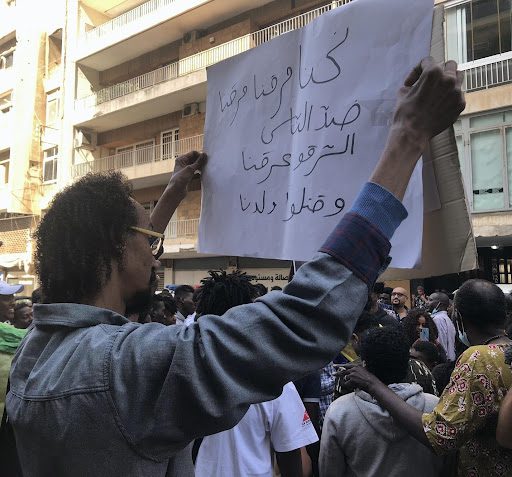

BEIRUT: Over one hundred Sudanese nationals gathered at the Embassy of Sudan near Hamra Saturday morning protesting the forcible removal and house arrest of Sudan’s prime minister Abdulla Hamdok earlier in the week by Sudanese military general Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan.

“Down with military rule! Down with Burhan!” the crowd chanted.

Sudan has been transitioning toward civilian governance for the past two years, after massive civilian protests starting in June 2019 prompted the removal of then-president and accused war criminal Omar Al-Bashir who spent thirty straight years at the country’s helm.

Many of the demonstrators in Beirut greeted one another with friendly familiarity and had also gathered during the Sudanese revolution two years ago.

Abdallah Yacoub IsHag, in his 50s, jovial and mustached, has lived in Lebanon for 17 years and spent “more time outside of Sudan than inside” working in different countries due to national unrest.

“I’ve hated military rule for a long time. I’m from Darfur. [The military] are the ones who decimated us,” he said describing the government-supported genocide in the early 2000s that garnered international attention.

“The military needs to know its place. . . . I’m not against the military but civilians should govern.”

Israa, age 30, brought her husband and children along to the assembly yesterday and was also in Lebanon during the time of the protests in Sudan in 2019. Then and now, she and others across the world took to the streets of their respective cities to voice their support for a transitional government in Sudan to replace former president Al-Bashir.

“International relations have improved” since the time of the transitional government, she said, “but internally we still need improvements. With the revolution we hope to eventually see them.”

She cited improvements in education and public health as important concerns that could be prioritized once key international collaboration had been secured, but she doubts that either will see much progress if military rule is reinstated.

The United States has already said that it will not disperse a promised 700 million USD aid package to Sudan and the African Union has suspended Sudan from membership in condemnation of last week’s coup.

Zahire, also in his 30s, has been working in Lebanon and traveling back to Sudan every five years since 1999. He agreed with Israa that the re-imposition of military rule is a step backwards after two years of small but steady improvements.

IsHag discussed how the military has collaborated with loyal militias to monopolize mines in Darfur, selling gold to the UAE and Saudi Arabia and hoarding the profits.

The fact that civilians in Sudan have hardly gotten to share in the wealth of the nation’s natural resources does not build trust that military rule will ever succeed or that General Al-Burhan will continue to allow a transition to a civilian government, despite Al-Burhan’s statements to the contrary.

According to IsHag, some Sudanese in Lebanon support the military intervention but “none of them are here [protesting] today.” He laughed.

As the morning wore on, the crowd grew in size and many began to dance to political songs played through a loudspeaker.

Both in and outside of Sudan, music has played a large role in the demonstrations.

“Whenever there is a revolution, they play this song,” Israa said.

Walid Al-Haj, in his 50s, hailed from the north of Sudan. Raised in Lebanon and born to Sudanese and Lebanese parents, Walid was in Beirut for a visit.

“I go back in two weeks.” He smiled wryly and added, “Hopefully they don’t kill me.”

The protest in Beirut continued without major incident, but Sudanese forces forcibly attempted to disperse Saturday protests in Khartom leaving at least three more demonstrators dead, according to the BBC.

As of Sunday evening, Prime Minister Hamdok was still under house arrest and internet access had been disrupted throughout Sudan presumably to hinder demonstrations and delay sharing documentation of the crackdown.