As the cost of food increases and the currency’s value continues to plummet, residents are growing more desperate each day. In mid-April, a man was killed and another two were injured in Tripoli after a dispute occurred during the distribution of food rations by an organization in the neighborhood of Jisr Al-Khannaq, Abou Samra.

As the news of the incident broke out, the general response was one of disbelief that the country had reached levels of poverty leading to conflict and death. But such measures of poverty have long existed in Lebanon, across neglected neighborhoods and cities that don’t make it into everyday news cycles.

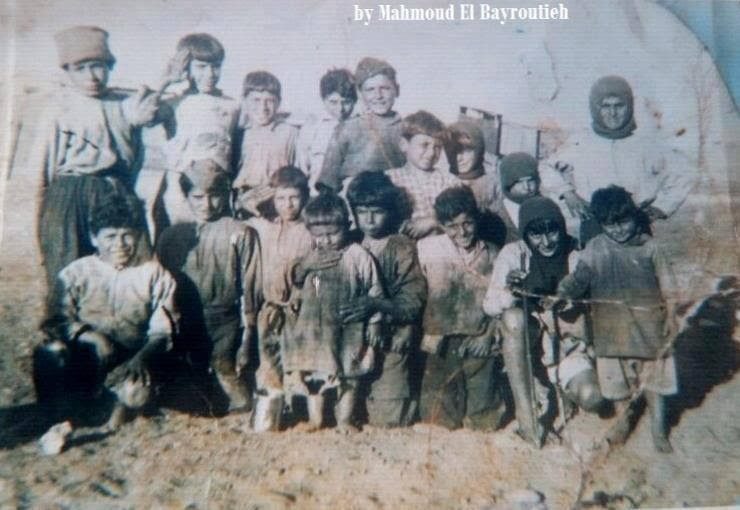

Tripoli, the poorest city on the Mediterranean coast, is one of those cities. A few kilometers away from Abou Samra lies the impoverished Hay al-Tanak, a neighborhood housing over 1,000 of the poorest Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian families in Lebanon’s second largest city.

In Hay al-Tanak, fights have commonly broken out over food rations and aid for years now, but the area is too neglected and cast aside for these disputes to be reported on in local media.

Volunteers and aid groups find it difficult to coordinate distribution in an area where conflict erupts as soon as volunteers carrying aid packages are spotted. They typically resort to the practice of targeting, which prioritizes families who have the most vulnerable needs, for such cases during aid distribution.

“To avoid conflict, we called the beneficiaries and asked them to meet us near Hay al-Tanak, instead of distributing within the neighborhood,” Rayan Karame, a Tripoli native who joined forces with a friend in 2020 to raise funds and distribute aid packages around Hay al-Tanak, told Beirut Today.

“This way, we were able to minimize the disputes that typically happen when aid is distributed in the neighborhood.”

Relief packages are usually given exclusively to the families who present the most need in the area. For example, families that include a large number of children or a family member with a disability are more likely to be considered for aid than others.

Rather than benefiting the community as a whole, this process of selective distribution results in social divisions.

A brief history of Hay al-Tanak

Despite being occupied with residents since the 1930s, Hay al-Tanak has been rendered invisible today.

Surrounded by the areas of Mina, Dam w Farez and Maarad, the neighborhood is hidden and isolated from the rest of the city, all while being absent from the official map of Tripoli –rendering it non-existent to the state.

The area was originally known as Haret al Jdideh, and only housed a few families from Tripoli. In Haret al Jdideh, housing units have a structure of a proper house, with concrete walls and ceilings. Only a few feature a tin (tanak) roof, since a lot of them were built years ago.

As the neighborhood expanded, tensions began to surface between the long-term residents and those who were coming to the area newly.

“Hay al-Tanak” earned its name after the area expanded into the surrounding land with the influx of more residents looking for affordable shelter. Makeshift houses were built with tin roofs and other materials that can be found on the street such as cardboard, sandbags, tires and concrete blocks.

“The Hara has always housed people from lower classes, but the structure of the area changed after the civil war and with the influx of Syrian refugees in 2011,” said Abou Riad, a resident of the neighborhood since his family settled there in the 1940s.

“In the early days, the neighborhood housed mostly Lebanese residents and a few Syrians, but today Syrian residents outnumber the Lebanese ones, especially that many of the Lebanese residents have left the area.”

As the neighborhood expanded, tensions began to surface between the long-term residents and those who were coming to the area newly.

Nidal, a long-term resident of Haret al Jdideh, was born in the area, as was her father. Her grandfather moved there in the 40s and bought a piece of land, where Nidal still resides today.

“In the Hara, there is a sense of community, as many inhabitants have been here for many years and know each other very well,” explained Nidal. “As Hay al-Tanak started to expand, we were worried because these new residents are strangers who typically stay in the area for a short time until they find different housing. We never really know who our neighbors are.”

Reproducing social divisions through aid distribution

As the number of residents increased, the area went from being a small settlement housing a few families to becoming an actual neighborhood. Today, it remains neglected by government officials, non-governmental organizations and civil society actors as well as residents of the city.

Ahmad, a long-time resident of the area who is also a member of the Municipality of Mina, said living conditions in Hay al-Tanak are only worsening. The region lacks all basic necessities, and there is a dire need for food aid as residents’ food security is threatened.

The education rate is almost non-existent among children and there are no public spaces, such as gardens or playgrounds, for them to spend their time in. In addition, the infrastructure requires complete rehabilitation. There is no water, electricity, or sanitation infrastructure.

“After the construction of Dam w Farz area in Tripoli, Hay al-Tanak became isolated, they killed the neighborhood and its residents,” said Ahmad.

The state’s negligence in the city not only contributed to the economic crisis but also opened the door for local politicians and CSO/NGO actors to attempt to fill the large gaps left. Considering the almost nonexistent state-sponsored social security plans, several initiatives have been established in the city to raise funds, assemble food packages, provide medication, cash assistance and much more.

Residents who have been excluded from aid express their frustration, even though they are not sure who it should be aimed at in most cases.

Residents who are benefiting from these services still highlight the gaps and structural problems of distribution.

Aid politics often neglect the needs of the community, reproducing social divisions and inequalities along the way. Hay al-Tanak, just like other impoverished neighborhoods in Tripoli, fell victim to regionalist discrimination from both state and aid initiatives.

“Aid does not reach Hay al-Tanak in an organized and thoughtful manner, that is if it even reaches us at all since we are often absent from the list of areas that NGOs operate in,” said Abou Anas, another resident of Hay al-Tanak. “In the rare case that it does, it is due to cooperation between the residents.”

Residents who have been excluded from aid express their frustration, even though they are not sure who it should be aimed at in most cases –whether it is CSOs distributing selectively, the state’s continued negligence towards the area, or fellow residents receiving more aid.

The anger and jealousy between inhabitants is giving rise to conflict and exacerbating tensions that were already forming between residents, especially in light of the rising levels of poverty during Lebanon’s economic crisis.

Easing tensions through community-based alternatives

The exclusion from humanitarian aid not only contributes to the economic burdens of residents, who are left to secure alternative sources of livelihood they can rely on, but also affects people’s perceptions of themselves and others.

As a result, feelings of shame and jealousy may plague their neighbourly interactions. Humanitarian aid seeks to provide the most vulnerable with means to cover their needs, meaning communities are altered by neglect and uneven distribution, causing an increase in social inequalities that are felt in residents’ everyday life.

Local community-based efforts have emerged as a way to combat this. Community members are organizing among themselves and negotiating with NGO/CSO workers, government officials and politicians to set aside selective processes and distribute relief packages to all residents in an equal manner, even if the amount of aid each family receives lessens.

Last year, the Haret al Jdideh Youth Association was established by residents of the neighborhood to work on coordinating aid distribution, looking after the neighborhood’s needs and providing aid to other residents by collecting donations from within the community.

“We saw how unorganized aid distribution in the area is, so we decided to take it upon ourselves to help the people of our neighborhood and take over the aid distribution process,” said Chawki, who is the head of the association. “We try to work with relief organizations to make sure every resident receives what they need.”

With the charity model, one built based on the unequal social bonds that are typical to Tripoli, residents are often treated as passive recipients.

To attempt to combat the social divisions in the area, a WhatsApp group was created with the other residents of Hay al-Tanak as members. The group is mainly used for cases to be shared anonymously, and for the collection of anonymous donations.

“This method drives those who receive aid to feel less embarrassed as they don’t know which of their neighbors donated, and people are more willing to donate since they don’t know who it’s going to. For instance, a while ago a resident donated to help a neighbor he wasn’t on good terms with without being aware since we kept the name anonymous,” explained Chawki.

Community-based initiatives, such as this one, present an suitable alternative to providing aid to those who are tired of the social stigma around needing and receiving relief support.

With the charity model, one built based on the unequal social bonds that are typical to Tripoli, residents are often treated as passive recipients and are not involved in the aid process.

The community-based grassroots model seeks to challenge this by involving residents in the planning and decision-making processes, or by including residents as active members of the initiative themselves.

“This is help from one poor person to another, without needing actors from outside our neighborhood intervening and treating us like charity cases,” added Chawki.

This kind of humanitarian work allows for the establishment of more sustainable, thoughtful and sensitive relief initiatives, while also empowering residents in their daily struggles against inequality and destitution.

More so, the recognition of all actors involved in aid processes creates a certain sense of social cohesion and community-based solidarity that transcends material needs.

It is important to emphasize the significance of consulting community members and involving them in the aid process to understand local preferences and needs. In contexts where inequality, division and othering are prominent, the community-based solidarity model can potentially play an integral role in alleviating the accumulation of ongoing crises and mending communities rather than breaking them.

See also | Riwayat, Episode 1: Tripoli ≠ Terrorism