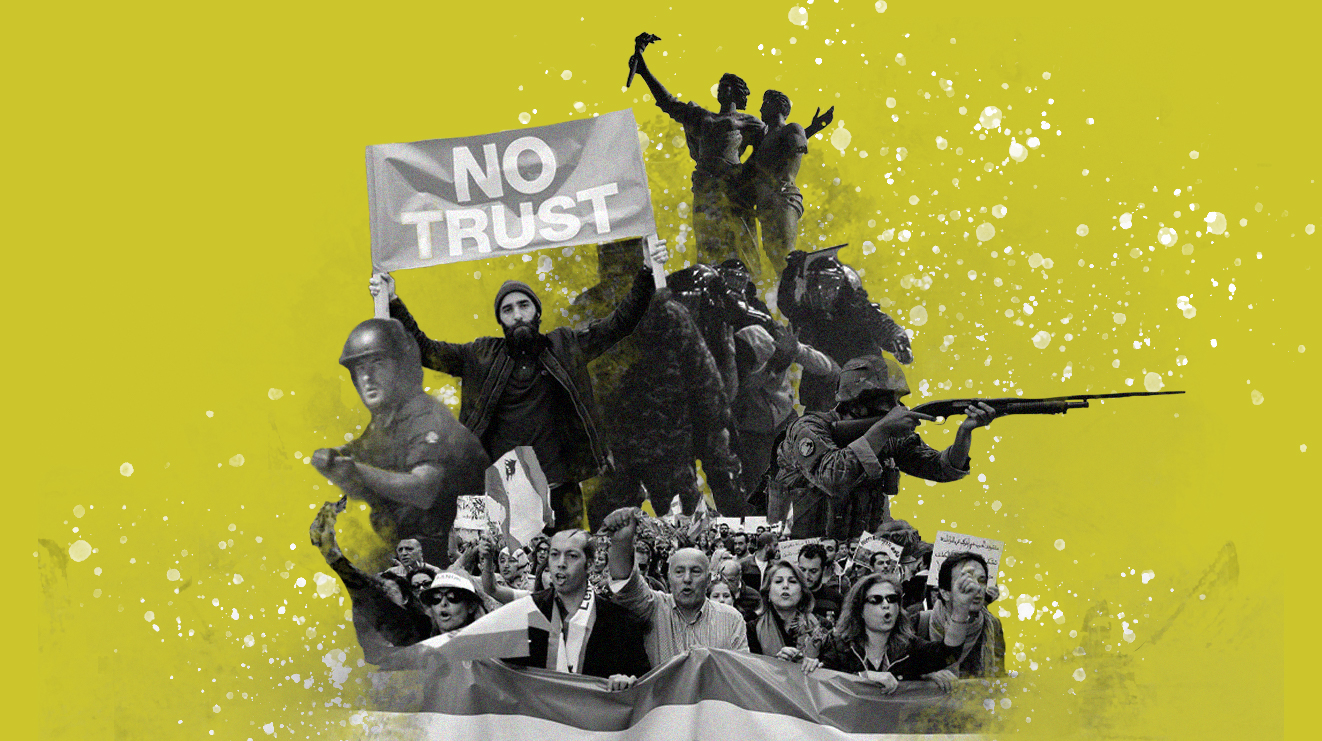

The militarization of police in Lebanon has grown exponentially over the past year, with escalating tensions growing between the police and unarmed civilians. As a result of this militarization –where local police take on the appearance, behavior and armament of a soldier at war– the public is less safe and less free.

Militarization has become a central feature of the dystopian COVID-19 reality, with warlike values escalating the risk of needless violence, jeopardizing lives, and undermining individual liberties.

Us vs. them: Escalation of police confrontations in individual encounters and protests

Just a few days ago, a video surfaced on the internet showing lawyer Ephrem Al Halabi illegally beaten, abused, and arrested following a clash with the Internal Security Forces. His car was also detained, although he was allowed to move freely in accordance with the decision of the Supreme Council of Defense.

Consequently, the President of the Bar Association, Melhem Khalaf, visited him at the station accompanied by the Bar’s secretary, Saadeddine Al-Khatib and the Justice Palace Commissioner, Nader Kasper.

When he was confronted by members of the ISF, Melhem Khalaf condemned the actions of the police officers.

“To the corrupt agents that defy the law, I am not with you, I am against you,” he said.

Following this assertion, a police officer refuted Khalaf’s statement by contending “you are with us according to the law,” to which Khalaf asserted “I am against you.”

Melhem Khalaf insisted on the release of lawyer Ephrem Al Halabi, who was later sent to a forensic doctor to have his condition carefully assessed.

Ever since the October 17 uprising, extreme force against protestors has become a recurring theme, with an unprecedented level of violence employed by the Lebanese army, Internal Security Forces, Riot Police and the Parliament Police during peaceful protests.

Footage from January 15 shows dozens of riot police coming out of police stations, beating protestors indiscriminately, and firing large quantities of tear gas when civilians retaliated by throwing water bottles or rocks.

Footage also shows protestors forcefully arrested and dragged into police stations, while others end up transported by the Lebanese Red Cross to nearby hospitals to be treated. The police spare no one, with children and journalists also falling victim to their violent and oppressive practices.

The SKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom reported more than 75 violations against media professionals between October 17, 2019 and January 20, 2020 –from beatings and tear gas to broken equipment and detainment.

Following the clashes, Interior Minister Raya El Hassan denied having issued orders to security forces to use force against peaceful protestors and journalists. This denial reinforces concerns about the absence of accountability and transparency not only amongst security forces, but on a nationwide level as well.

Speaking of accountability, tens of thousands of protestors took to the streets on August 8 to call for accountability as a result of the tragic explosion in the Port of Beirut.

The protestors who threw stones and other projectiles at the army were faced with tear gas, rubber bullets, and birdshot fired from shotguns. At least 728 people were injured that day as a result of police brutality.

Al Jazeera reports a clear violation of international standards on the use of force after analyzing videos and images of clashes between civilians and the police, and after examining medical documents that pertain to the lethal use of weaponry.

When Human Rights Watch provided verified evidence showing two soldiers from the Airborne Regiment firing live ammunition towards protestors on August 8, the army publicly denied the violation. Similarly, when Human Rights Watch attempted to summarize its findings to a Parliament Police official during an August 19 phone call, he hung up.

“This primarily shows that some security agencies, and in other cases individual officers in some of those agencies, are acting as if they are members of paramilitary forces independent of the state” explains Rabie Barakat, who was shot in the eye with a pellet gun as a result of the security forces’ excessive use of force on August 8. “It also exposes a predisposition to use brute force regardless of any legal restraints, one that leans on an astounding dismissal of accountability measures.”.

The United Nations has set basic principles for the use of force which outline that all other non-coercive means must first be exhausted and security forces must “exercise restraint” and “minimize damage and injury.”

Yet, security forces have clearly violated international standards. Lebanese security apparatuses behave and look like soldiers fighting on the front line of a war rather than public servants, which in turn promotes a sense of fear and mistrust among the people.

Although the public expects police to only use lethal force in extreme circumstances, militarized police are using lethal force against civilians more frequently, resulting in more civilian injuries, deaths, and arrests.

This militarization fosters a police culture based on an “us vs. them” mentality which sets Lebanese protestors as the threatening enemy.

War at home: Increased militarization in times of pandemic

By utilizing the cover of public health safety measures, the politics of “opportunistic authoritarianism” is already in play, enforcing a broad range of anti-democratic policies and a wave of repression.

As a result of the already escalating police militarization, overcoming the pandemic looks like fighting a war, with security apparatuses serving to deepen the ends of those in power. The lockdowns in Lebanon are thereby comprised of inconsistent curfew check-ups which depend on the officer’s mood or even the religious/ political sensitivity of the region.

“The escalating militarization in Lebanon is in sync with how the sectarian system operates,” said Karim Saffieddine, member of the secular youth network Mada. “Enforcements are inconsistently applied onto citizens depending on aspects such as class and status amongst different regional client networks. It’s no doubt the interest of the regime to sustain and reproduce itself by utilizing the pandemic as a pretext to curb oppositional mobility.”

Sectarian, authoritarian politicians are energized as a result of the proliferating emergency laws. Slavoj Zizek describes “the ongoing spread of the coronavirus epidemic has also triggered vast epidemics of ideological viruses which were lying dormant in our societies.”

While xenophobia and classism haven’t exactly been lying dormant in Lebanon, they are shining through with the inconsistently imposed lockdown fines, some of which soared to over 20,000 fines per day. This exemplifies the spread of the ideological virus and its apparatus of police repression, with compulsory fines being enforced unfairly depending on social statuses and the nationality of the citizens (the poor and the refugees mainly bearing the brunt of such restrictions).

At a time when the police are meant to ensure peace and order, their very presence reinforces the underlying social problems of Lebanon.

Challenges of the security sector reform in Lebanon

Most Lebanese government institutions suffered substantial damage during the war. During the post-war phase, the internal security institutions were not rebuilt adequately, especially in terms of ethical standards and mechanisms of inspection and accountability.

Several overarching flaws exist in the Lebanese security apparatus, with corruption at the heart of the law enforcement agencies. From bribery and sectarian nepotism, to outright defiance of international standards of the use of force, the security sector in Lebanon is in dire need of reform.

Systemic accountability must be established, and the inspection of law enforcement agents should be made regular and rigorous. This should be the first step towards the reconstruction of a structure founded on corruption.

Moreover, the Lebanese security apparatus is still characterized by a multiplicity of security organizations, from the Lebanese Army, the Parliament Police, Riot Police and the ISF. This in turn encourages rivalry and weakens accountability and coordination.

Instead, different ISF task teams should be appointed with specialized tasks, in order to gain better experience and develop specialized expertise. Additionally, the representation of women would also be an efficient step towards fundamental reform within the security sector.

This step would require a much-needed modification of Law 17, which delegitimizes the incorporation of women to the police force.

If there is anything we have learned over the course of the last couple of months, it’s that change comes slowly but surely.

However, for change to actually stand a chance in a country deeply entrenched in corruption, we must discover the corruption at every level in every major institution, including the military and the police.

“The aim is to push for real accountability, to make this strive for fundamental change, along with the corresponding sacrifices, our means to move for the better. To alter and reconstruct rather than settle for deconstruction,” explains Barakat. “And this requires rational perseverance rather than impulsive reactions, no matter how tempting the latter are, and no matter how legitimate they seem to those who were injured, me being one of them.”

Corruption persists in a framework that is far more expansive and far vaster than just the governmental framework. That’s why it is important for us to develop an analysis of why we are observing a clear escalation in police militarization, and to push for systemic accountability and reform.

Police militarization in Lebanon is a serious problem that jeopardizes our individual liberties, and pushes forward the agenda of the authoritarian regime. The people can and should not have to carry around onions every time they protest, in fear of the agonizing teargas.

Now, imagine what we could do if we had the police and the army protesting side by side with us, standing against the warlords that ruined our country. Reform in Lebanon starts with the demilitarization of law enforcement agencies and with the establishment of uncompromising accountability.