Ever since the beginning of the October 17 revolution, government forces have detained, interrogated and arrested over 100 activists for protesting or expressing opinions on social media.

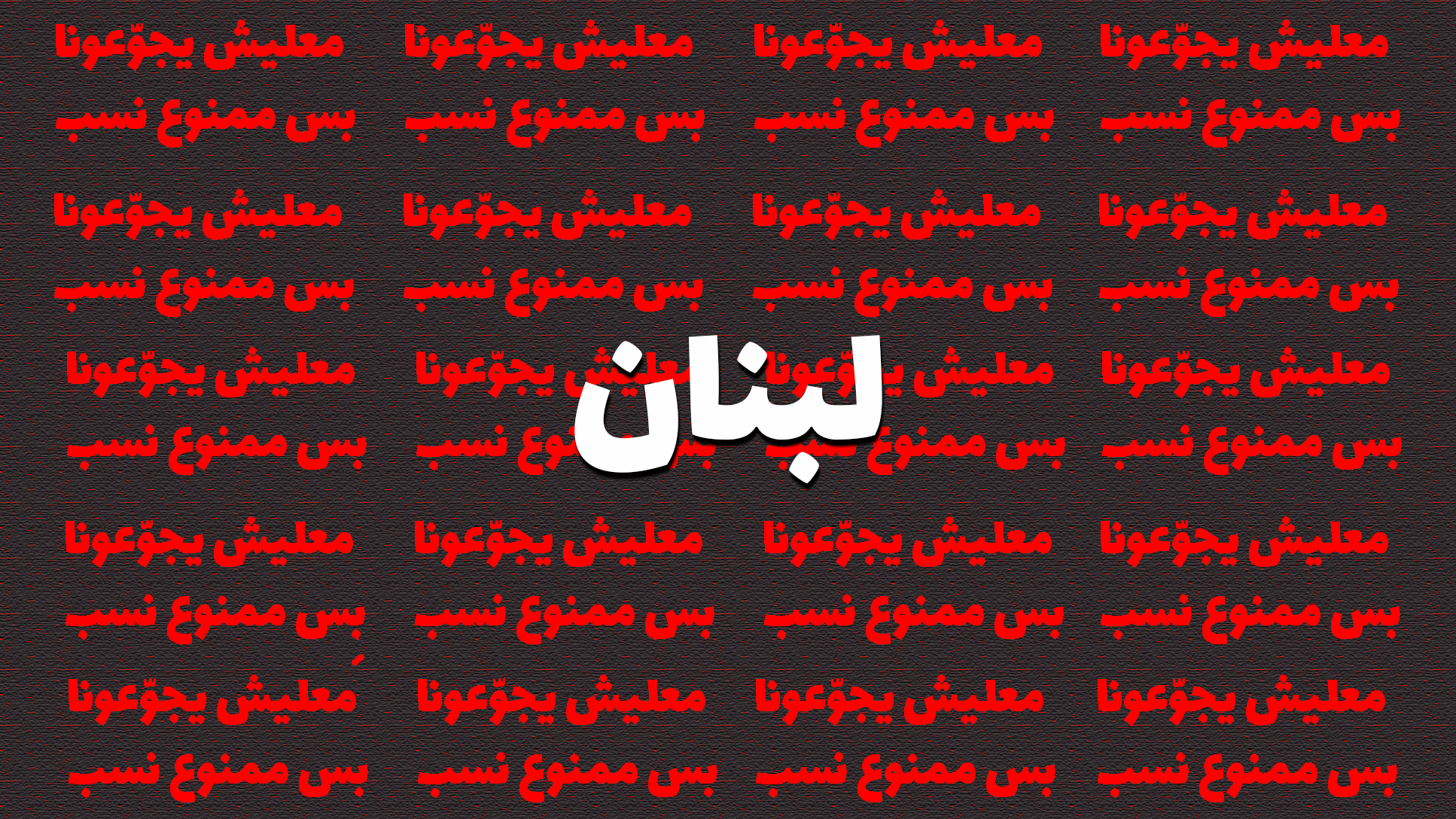

In the last few days specifically, the Lebanese public has witnessed a sudden surge in crackdowns against free speech. The arrest of activist Michel Chamoun, under the pretext of “insulting the president,” is just one example of what might be one of the most challenging times for freedom of expression in the country.

Background

This trend is not new to the country. Periods of protests and political movements in Lebanon are usually followed by crackdowns on free speech as protesters express their anger towards the ruling class.

In the calm period that followed 2015’s “You Stink” protests, the Lebanese government accentuated its oppression of activists and protesters by arresting large groups of protesters who were considered “active” in the movement and tried to interrogate and scare them into silence.

According to Human Rights Watch, 3,599 cases of defamation, libel and slander were investigated by the Lebanese Cybercrimes Bureau between January 2015 and May 2019 –a significant increase from previous years. Of these cases, 1,451 were investigated in 2018 alone.

Recent Developments

What is taking place now is a significantly amplified version of what happened then. Fears of repercussions against free speech resurged on May 15 when Minister of Information Manal Abdel Samad gave a statement regarding journalists from the Editors’ syndicate.

“We are studying prison sentences [for journalists] that would not be implemented within broad constraints, but that would take into account the controls that protect the state, its prestige, and its pillars,” Abdel Samad said.

Abdel Samad then gave a statement to Voix du Liban the next day. She expressed her support for media freedom but claimed it should not infringe on national security and dignities.

Organizations that advocate for freedom of expression shared their concern following this statement, saying that these policies are known within governments that try to fearmonger and oppress media freedom.

On Monday, June 15, state prosecutor Ghassan Ouweidat issued a decree that called for prosecuting any person who insults the president on social media. Lebanese law already punishes insults towards the president with a sentence that can reach up to two years in prison. Michel Chamoun was arrested following his criticism of this decree and the president.

Following this event came a statement on June 21 from the head of the Beirut Bar Association Melhem Khalaf, whose election was hailed as a victory for protesters.

The statement however criticized the use of curse words to express one’s dissent and considered that curse words transcend one’s right to freedom of expression. Independent groups expressed their disappointment in the statement for its tone and for “succumbing to the police state.”

The next day, president Michel Aoun stated his will to differentiate between the right to freedom of expression and the right to insult. He also called for the creation of laws that limit the citizens’ right to insult. Human rights groups criticized Aoun’s statement.

“International human rights law makes no such distinction,” said Aya Majzoub, Lebanon and Bahrain researcher for Human Rights Watch, in a tweet responding to the president. “The mere fact that expressions are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify imposition of penalties. The right to free speech embraces even expression that may be regarded as deeply offensive.”

Intl human rights law makes no such distinction. The mere fact that expressions are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify imposition of penalties. The right to free speech embraces even expression that may be regarded as deeply offensive. https://t.co/U9OmrxYHSF

— Aya Majzoub (@Aya_Majzoub) June 22, 2020

The Lebanese government further emphasized on what, to them, are limitations to free speech on Thursday June 25 during the “National Meeting” at Baabda Palace.

Instead, the final statement of the meeting mostly consisted of broad calls for national unity and dialogue. Participating members expressed their support for limiting freedom of expression by forbidding “humiliation” and swear words.

Amidst these developments, political parties seem to have also been going after critics in an attempt to reduce popular discontent regarding them.

Political Parties’ Meddling with Free Speech

Political Parties have regularly used Lebanon’s broad defamation laws in order to silence activists and opponents over the last few years. The protests that started on October 17 led to an increase of this practice.

The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), the president’s party, was already the main focus on the matter for filing complaints and pressing charges against critics at an increasing rate since 2018.

In recent months, several activists and journalists (including Gino Raidy, Dima Sadek, Charbel El Khoury, Mirna Radwan, among others) have been interrogated or arrested for charges that include insulting the president, insulting a figure in the party (including party leader Gebran Bassil), protesting against FPM politicians and allegedly inciting sectarianism.

The Lebanese Forces, often seen as the FPM’s main opponent, have also resorted to the law against critics in the past. On May 30, they released a statement saying they will prosecute anyone who will criticize late president-elect Bashir Gemayel, an important figure in the party’s history.

Violence and threats are also often used against activists. Bashir Abou Zeid, editor-in-chief of the October 17 Newspaper, criticized speaker of parliament and head of the Amal Movement Nabih Berri through a Facebook post on May 22.

Later that day, he was followed by civilians in the southern village of Kfar Rumman. The civilians then beat him and allegedly tried to kidnap him.

As the economic crisis keeps unfolding and corruption remains rampant, having free citizen and journalistic voices is essential in order to properly understand what the public needs. The future of freedom of expression in Lebanon is still unknown, but recent events warn of a potential era of stronger censorship.