Both celebrated and cursed, the Lebanese resilience –or capacity to endure the toughest of situations and contexts, is engraved in the known saying: “Like a Phoenix, Lebanon shall always rise from its ashes.”

For the past 50 years, the Lebanese have overcome wars, terrorism, security clashes, and Israeli aggressions, managing to rebuild their homes, secure their livelihoods and raise their children. They have endured all types of crises, up until the most recent monetary and financial strains, all while suffering from a political class that has been feeding off State spoils for decades.

As greater corruption lies among the most crucial challenges, it seems the capacity of the Lebanese resilience has reached a breaking limit. Back in 2012, I had observed that:

“The current mafiocracy is a collection of war makers, whether past or present. They have brought conflict, destruction, displacement and today, greater corruption to a point of social and economic depletion. As such, they represent the greatest menace for the future of the country. They are, forever, indebted towards the children of the civil war and the generations beyond.”

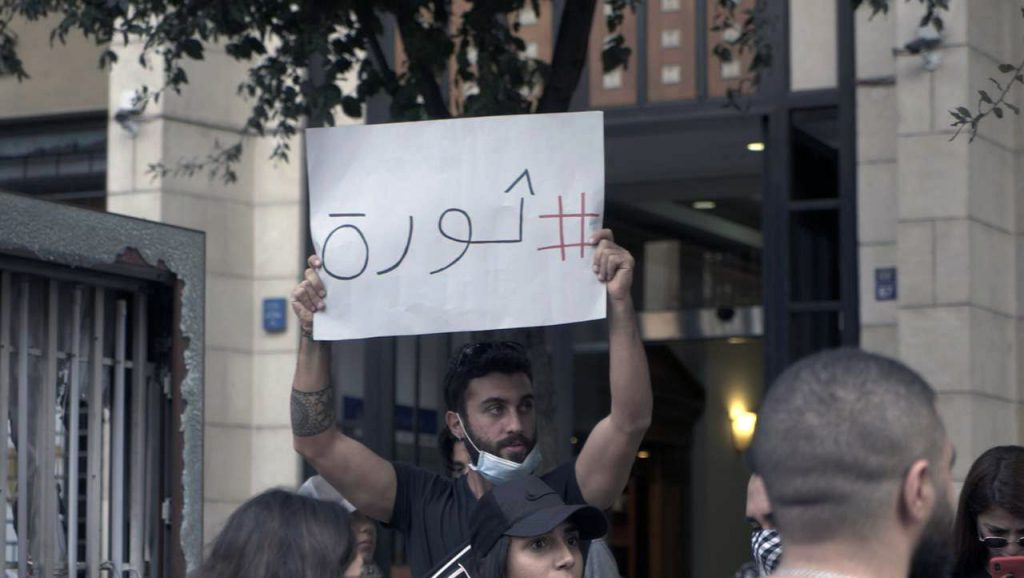

Through the protests, the Lebanese appear as if they are ready to call this debt, both financial (public debt represents 150 percent of the GDP, the third highest rate in the world) and political, which the ruling class had been accumulating in their names.

Only three days into the protests all over Lebanon, the path of how events will unfold remains unclear. Yet unprecedented paradigms are emerging and can be grouped under these points.

Stolen Future: Youth Are Voicing Their Discontent

Firstly, the protests that have swept across towns and villages in all governorates are gathering a large youth representation, university students and even those still attending secondary school.

The generations born after the civil war and the ones born after 2000 are voicing deep discontent at the abnormal State they are living under. Despite having inherited the Lebanese civil war narratives and the recent period’s blame games, younger generations prefer to concentrate on their future, which was confiscated by the petty political schemes and greater corruption, leading the country to socio-economic abyss.

Many of those youth are living this abyss already, and have been voicing it on live television for three days now in a sort of therapeutic Hyde park: no jobs, no income, no emigration promises, scarred dignities over basic services denied.

They represent those flesh-flayed by the Lebanese economic model, mixing neo-liberalism and a semi-rentier economic structure guaranteeing wealth to established oligarchs and their political patrons.

Karate Queen: Women Are At The Forefront Of The Protests

That said, the protests have highlighted a rising figure, in correlation with the shifted paradigm in overcoming the long-lasting acceptance of the confiscated State: women.

Adding the overthrow of patriarchy to the struggle list, Lebanese women are standing on the front stage of the protests defying the ruling class. As a matter of symbol, the footage of the karate “queen” kicking an armed bodyguard in downtown Beirut has become one of the emblems of the demonstrations.

Admire this badass Lebanese protestor, she got the thug properly with that kick pic.twitter.com/bxYMBIadcJ

— Karl Sharro (@KarlreMarks) October 17, 2019

Only ten years ago, among the campaign slogans for the 2009 elections was the controversial banner calling women to vote, that read: “Sois belle et vote” (Stay beautiful and vote), raised by the Former Patriotic Movement.

In today’s Lebanon, Lebanese women are leading the way in voicing a real opposition to the way public affairs are run in the country. Paula Yacoubian, who is the only independent elected official from civil society-led lists in the 2018 parliamentary elections, is often regarded as a role model for regularly shaking off sexist and insulting attacks.

Kellon Yaani Kellon: Political Parties Are No Longer Untouchable

Secondly, one could notice the fall of some taboos in the present protests in different regions: open insults on television by barefaced demonstrators to their own sectarian leaders or the burning of photos, slogans, offices and businesses belonging to the most prominent politicians in the country; such actions have altered the face of street opposition in Lebanon.

The desacralization of the political sectarian entrepreneurs is among the most flagrant variations from precedent demonstrations, reaching deep into each of the different leaderships.

If the slogan “we mean every one of them” (kellon yaani kellon) isn’t new, the expression has taken a different connotation when people overcame the fear in talking at previously untouchable Shi’a figures in unprecedented forms.

Countless media interventions from underprivileged youth and even older citizens from Shi’a neighbourhoods have addressed serious recriminations to both Amal and Hezbollah.

After Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary General of Hezbollah, gave his speech on October 19 warning the demonstrators that the regime could be toppled, he was met with strong reactions in the street from persons living in the Beirut southern suburbs and other prominently Shi’a areas.

“It’s the very first time I don’t agree with the Sayyed,” said one protester on television. “Nasrallah does not get to decide for us, it is we the people who decide,” said another demonstrator criticizing his stance.

In Tripoli, banners of Prime Minister Saad Hariri and former Prime Minister Najib Mikati were torn down. Druze leadership of Walid Jumblatt is also under heavy attack within his own base, not to mention the regular (and more common, given its greater political diversity) bashing of Christian figures and officials.

Calls for resignations and removal of the zuama are a major (but not unanimous) expression of the protesters’ current state of rage. Thus, the new mood and tone of the on-going protests represent an additional indicator of how patience is wearing thin towards the ruling class at this stage.

Free flowing: Protesters Are Not Letting Political Parties Hijack Their Movements

The last point worth mentioning in the recent events is the absence of leaderships steering the protests. Current opposition parties rushed but failed at positioning themselves so far at the spearhead of the marches, such as the Kataeb, headed by Samy Gemayel or “Citizens in a State”, headed by former Minister Charbel Nahas who demands a Civil State.

Moreover, “Civil society” political activists from the 2015-2018 period are displaying a low profile: the leaders of the waste management crisis protests back in summer 2015, who took to the streets and improvised youth movements (You Stink, We want accountability, etc.), avoided stepping into the pilot’s seat and rather left the different efforts flow freely.

The same goes for the electoral groups that emerged from civil society during the elections from 2016 (municipal, Beirut Madinati) and 2018 (the largest being Kulluna Watani).

If many of them remain very active on social media, they haven’t formally invested the field or claimed visibility. Fearing to confuse the protesters, these groups understand their limits in synchronizing and carrying the multiple demands from the waves of discontent, and will be struggling in planning the next stages of their combat against the hydra of the political regime, as the density and rhythm of the protests are bound to increase in the coming hours and days.

Next Stop: Fear, Vacuum, And New Voting Behaviours?

Despite being extremely well-rooted, the Lebanese ruling class was shaken by the current developments. It is undergoing a strong fracture, not only vis-à-vis its traditional opponents, but with the very own constituents it can no longer support today because of the acuity of the budgetary and financial pressures, both on a national and international level. The latter have greatly amplified since the 2018 legislative elections, during which the ruling class has regenerated some of its political legitimacy, after postponing the elections for more than four years.

Today the authorities are facing a direct backlash from their voters and will need to reverse the pro-taxation trend that remained unchecked for so many years. This won’t be an easy decision to actually implement, given the alternative would be to tap into other streams to increase public revenues. Fierce opposition to that will be inextricably met from all segments.

Eventually, the guardians of the regime will attempt to use the fear card, warning against chaos should a governance vacuum occur. Usually, political and sectarian entrepreneurs excel in buying time for themselves vis-à-vis regional and international players.

This time, they will resort to similar tactics to shield themselves from accountability vis-à-vis their own citizens, whose endurance will be put under severe test.

As such, the confrontation is likely to continue with unclear outcomes at this stage. If the 2015 movements had led to the surfacing of political alternative groups and actors, we have yet to see whether the 2019 protests will trigger the emergence of new voting behaviours in Lebanon.