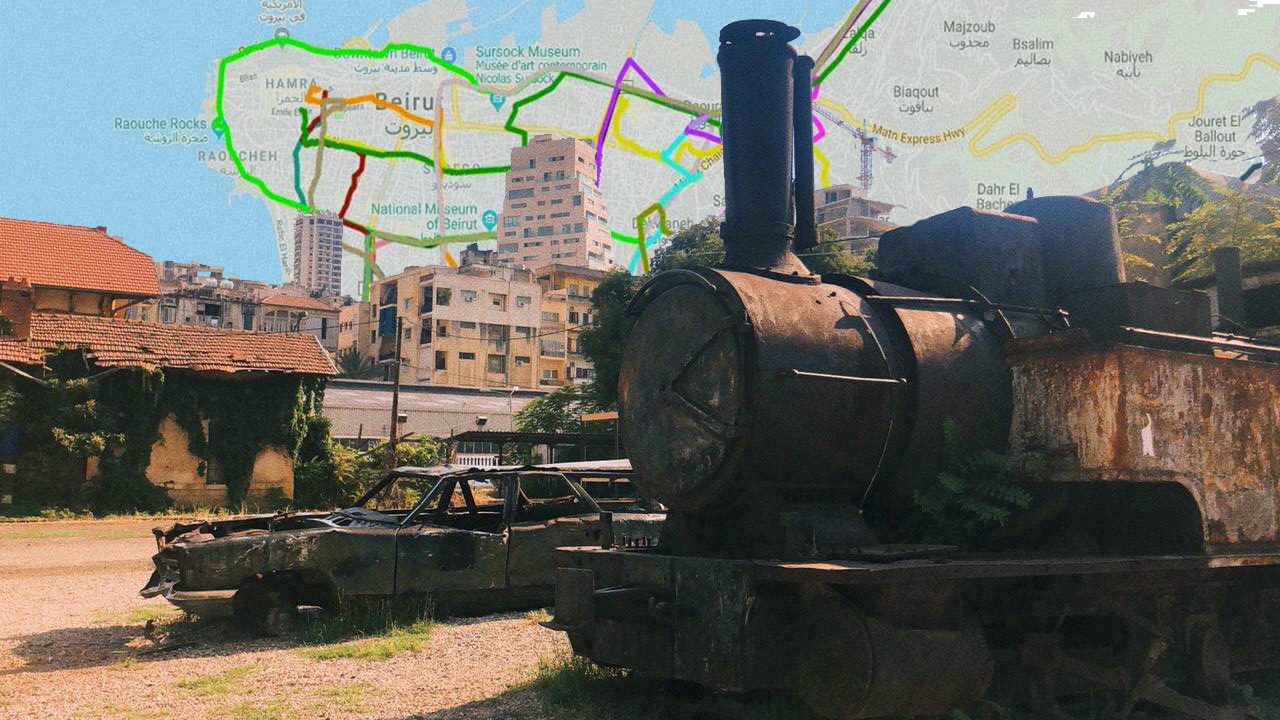

A walking tour by the Bus Map Project explored the country’s past of public transportation and delved into the possibility of reviving or redesigning the forms of Lebanese public transportation today, mostly looking at trains and buses.

Led by the Chadi Faraj, the Rider’s Rights (Bus Map Project) NGO’s founder, the Toot Toot A’ Beirut event was the result of a collaboration with Train/Train Lebanon. The former encourages people to use public transportation through an online platform and flyers that explain how to work the system, while the latter aims to both bring back a new train system to country and preserve heritage sites.

“The majority of the people who use the bus, do so because of need,” explained Faraj, highlighting how the Lebanese public transportation system is negatively perceived.

While this might link back to bourgeois stigma on mass transit, it is also ultimately connected with the system’s lack of maintenance: Dirty busses with broken tail lights and speeding drivers don’t make the best case for public transportation. If our public transportation systems were regularly updated and maintained, residents might begin to use them by want rather than need.

A majority of the population ignores the importance of updating these systems and having good public transportation in the country, a sad reality reflected in the event. Toot Toot A’ Beirut’s turnout was just shy of twenty people, more than half of which do not use public transportation themselves. Without breaking the stigma surrounding public transportation, these unfortunate facts are unlikely to change.

Why Do People Look Down On Public Transportation?

In the past, public transportation was more than just an integral way for people to get around, it was fundamental for the formation of a city. By providing a cheap mode of transportation that ultimately leads to places where specialized services and government officials are situated, tramways connected citizens with government officials and led the way for the formation of “sahat” or public squares–both important steps in building up the city and helping people “rally together” in the revolutionary sense.

Faraj stressed that it was relatively common for people to “rally together” in protest of corruption in public transportation systems that make their everyday lives easier. The stigma, it appears, came as the maintenance and quality of public transportation dropped. In Lebanon, this happened as the civil war intensified.

The pervasive consumer capitalist mindset we’ve been brought up into doesn’t help either. Busses and subways are, in their essence, cheap ways to get around. When we’re taught that owning our own luxury cars is supposed to bring us the ultimate satisfaction, nothing about public transportation could ever be appealing –even if you’re going to have to drive around Mar Mikhael for half an hour before either finding a parking spot or caving in to paying LBP 10,000 for valet services. In Beirut and across the globe today, your method of transportation doubles as a marker of social status.

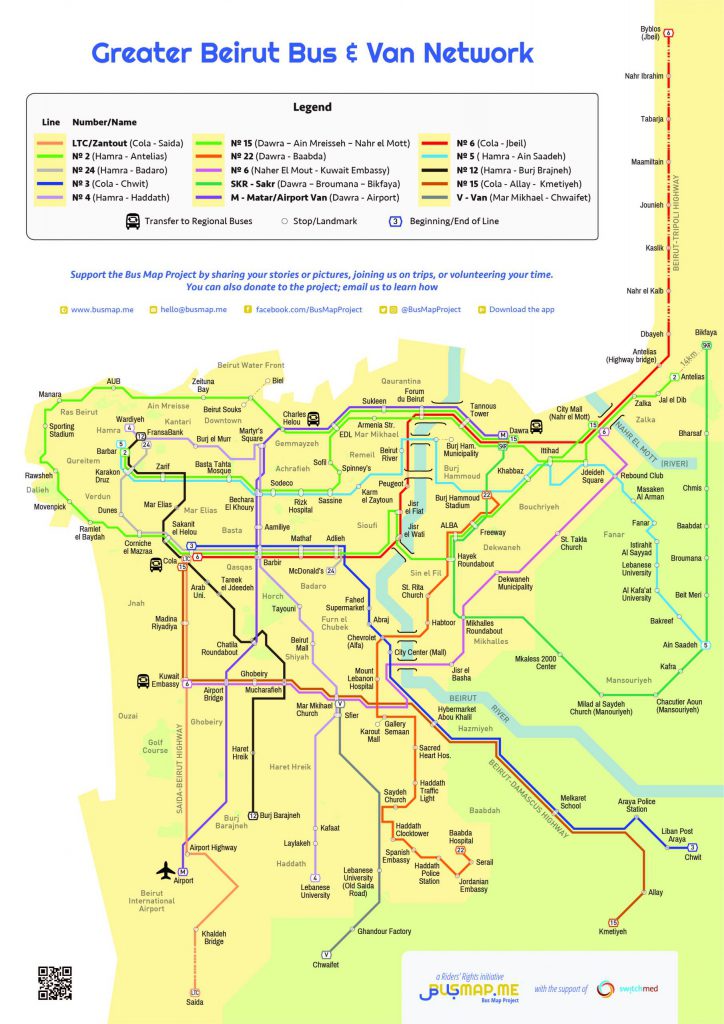

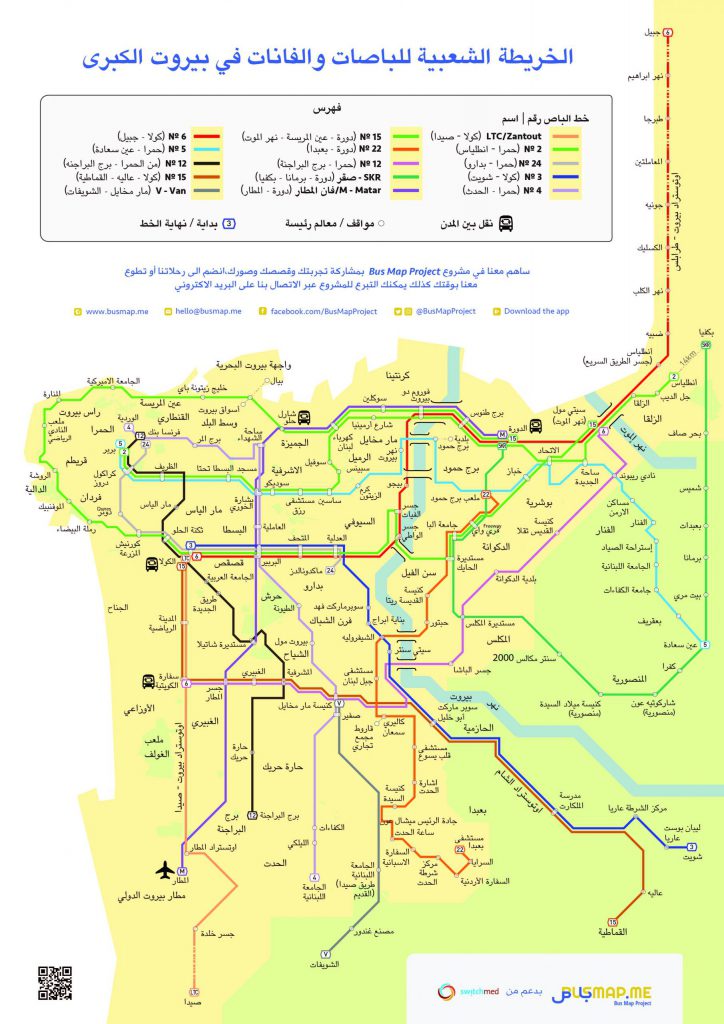

Regardless, updating the public transportation system and presenting a new standard, which is the ultimate goal of Chadi Faraj’s Riders Rights and similar organizations, can get the conversation started for a majority of us. Faraj says the maps passed out as part of the Beirut Maps Project, along with access to their platform, has encouraged more people to use public transportation.

Lebanese Public Transportation: By All, For All?

The development of a decent public transportation system may ripple out positivity within Lebanese society in more ways than one: Getting rid of the deadly traffic which every Lebanese person knows too well, fixing the huge dent left by petrol costs in the country’s GDP, and even opening up thousands of job opportunities and stimulating the economy.

Yet, when asked about the ultimate “dream” for Lebanese public transportation, Faraj talked very little about using less cars. He focused more on the creation of a public space for all.

“Public transportation plays a part in co-existence,” said Faraj, who hopes that a decent Lebanese public transportation will bring people closer. “The ultimate dream is that people would commute together, hear each other’s problems, and humanize one another instead of continuously demonizing the enemy.”

While staying critical of his own dream, Faraj hopes that this would unravel somewhat naturally as the Lebanese public transportation system is improved upon and a comfortable public space is presented in the country.

“The dream system would be for kel el kel (all of all),” Faraj described his dream. “All classes, people in the sense of everything, even those in wheelchairs. It’s inclusive for all.”

Sectarianism and No Real Plans For Public Transportation

Faraj recognizes that sectarianism can easily manifest in these public systems. He highlights how people in Lebanon would graffiti the tram, when it existed in the country, if they knew it was going to pass near a certain politician’s house or areas dominated by opposing political sects.

It would be extreme to depend on the revamping of a public transportation system as the savior of a society drenched in inequality, but even if it is not the way to achieve an inclusive public sphere, it can be one of the many factors in that direction. Yet, despite several proposed projects that hope to revive Lebanese public transportation, no actual political decision has invested in its implementation.

Reworking the conversation does not only carry hopeful economic implications, but social undertones that should not be ignored when discussing the possibility of a successful Lebanese public transportation system.

If a project were to go through, its success would depend on cooperation and integration. In Lebanon, two systems of “public” transportation exist: The first being formal, with private entities or the government setting fixed schedules and stops, and the second being informal, which fills the gap when formal systems fail by functioning organically and on demand according to how different individuals operators work. Composing the new standard for Lebanese public transportation and breaking the stigma needs formal and informal systems working together.

”There needs to be a way for all employees to participate in the formation of the system,” added Faraj. “Everyone working, be it the people working on the lines, the municipality, or the operator, should give their input.”