Amidst a tide of hate speech and scapegoating Syrian refugees, there has never been a more pressing time to call out the myths and fictitious claims made by the current political class in Lebanon about this group of people.

The agents of the current tense political climate have asserted and continue to proliferate a hostile narrative towards Syrian refugees, portraying them as an internal threat adversely affecting the Lebanese economy. Some politicians claim that Syrian refugees have led to an increase in unemployment and decline in the quality of jobs, that they do not pay taxes and are the reason for the crumbling infrastructure and environmental degradation, and that they are the primary cause of the waste crisis in Lebanon.

Isolated security incidents, such as Arsal in 2014 and Mizyara in 2017, have been used by both local communities and public figures to insight and perpetuate nationwide hatred and hostility towards refugees. This has led the Lebanese public to adopt an even more antagonistic attitude towards Syrian refugees, and to express outrage at the presence of refugees in Lebanon, calling for their return.

In recent developments, public figures have been fixating on the impact of Syrian refugees on the Lebanese economy, and more specifically the labor market, where Syrian workers are allegedly replacing the Lebanese labor force because they are willing to accept longer hours for lower wages.

But how credible are these claims?

Data and Accuracy (or Facts)

Statements made by influential political figures with a certain degree of legitimacy are not necessarily accurate or factual.

This is especially true in the case of claims concerning the impact that the Syrian refugee influx has had on the economy and labor market, considering that the most recent national labor market study by the Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) dates back to 2009.

Since the arrival of refugees, there have been very few substantive studies on the impact of Syrian refugees on the Lebanese economy and labor market (ILO 2013). There have, however, been a number of studies on the impact of the Syrian conflict on the Lebanese economy (World Bank 2013; World Bank 2015, UNDP & UNHCR, 2015), but none make a distinction between the effects of the Syrian conflict and that of Syrian refugees.

The lack of comprehensive data on the impact of Syrian refugees, combined with the absence of data on the Lebanese population, makes it difficult to make accurate estimations without an extensive macroeconomic study, an assessment that the Government of Lebanon (GoL) and its agencies have yet to conduct.

However, the political class has managed to succeed in making inflammatory statements based on presumptuous statistics and has constructed a figure to scapegoat for all the political, economic, social, and environmental turmoil in Lebanon that predate the arrival of Syrian refugees.

The political gridlock and social division which have so far defined Lebanese politics, coupled with the structural composition of the Lebanese economy as one that relies on low-productivity sectors, have hindered any form of progress in the implementation of policies that could facilitate the alleviation of poverty and sustainable job creation.

Busting Myths in the Labor Market

Prior to the influx of refugees, the World Bank (2012) found that the Lebanese economy could not absorb the incoming labor force. Between 2004 and 2009, the Lebanese economy was only creating 3,400 jobs for approximately 19,000 new entrants into the labor market annually.

Jobs seekers in Lebanon faced and continue to face three main challenges: (1) The structural composition of the Lebanese economy, where job creation was primarily concentrated in low-productivity sectors such as wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles, transportation and storage, accommodation and food service activities, and real estate activities. Between 2004 and 2009, the World Bank found that the Lebanese economy was moving away from high-productivity sectors to low-productivity sectors leading to a decrease in both the creation of decent jobs and the likelihood of long-term economic growth; (2) A mismatch between the type of jobs being created by the Lebanese economy and their high-skill sets, leading to an increase in youth emigration in search of employment; (3) The lack of mobility in employment between formal and informal jobs.

The assumption that Syrian refugees and the Lebanese labor force are competing for the same jobs is farfetched. While Syrian refugees did adversely affect wages and the quality of employment in the low-skilled labor sector, since they are willing to accept longer hours for lower wages, they did not significantly affect the high-skilled Lebanese labor force.

The relatively low educational level of Syrian refugees, their higher unemployment rate, and the legal restriction on their access to the labor market have substantially diminished the likelihood of competing with the higher educated Lebanese labor force over high-skilled jobs.

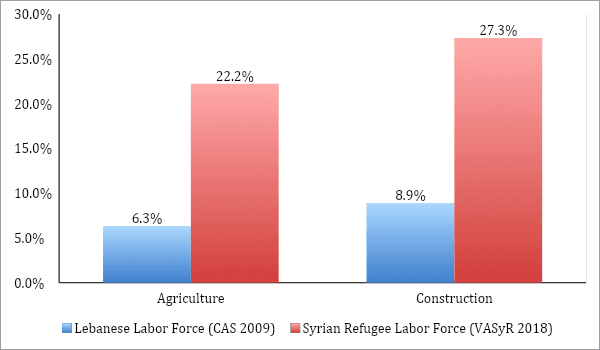

According to the UNHCR, UNICEF and WFP (2018) annual Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees (VASyR), approximately 50 percent of Syrian refugees work in the sectors of agriculture and construction. According to the last CAS survey on the labor market, only 14 percent of the Lebanese labor force worked in those sectors.

Only 32 percent of the Lebanese labor force was employed in low-skilled labor compared to more than 60 percent of Syrian refugee workers, where low-skilled labor constitutes the lowest segment of labor performed by Lebanese.

On the contrary, the labor supply shock of low-skilled Syrian refugees has provided cheap labor to Lebanese companies, where the influx of Syrian refugees has allowed companies to reduce their payroll costs and thus their overall costs, and has benefitted them during the current period of economic downturn.

The arrival of refugees has also filled in a gap in sectors where local labor supply is very low (construction, agriculture, home services, supermarkets, etc.), such that rather than competing with the Lebanese labor force, Syrian refugees are competing with unskilled migrant workers for low-skilled, low-paying jobs.

Another statement that has also been circulated is that more than 500,000 Syrians are working in Lebanon. While this is true, what public officials neglect to mention is that the ILO has estimated that 300,000 Syrian workers were already employed in Lebanon prior to the crisis.

According to the estimations of the Refugees=Partners project, of the 1.5 million Syrian refugees present in Lebanon, approximately 130,000 to 200,000 of them are employed.

Public officials and government agencies have also made comments concerning the legal status of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and the illegality of their employment in Lebanon. However, the rise of undocumented Syrians is a direct result of the policies and practices implemented by the GoL’s agencies that have made it strenuously difficult for Syrians to attain legal residency in Lebanon.

An Aggressive Policy of Return

Lebanon has refrained from ratifying the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol that guides the legal framework for refugees. The 1951 Convention stipulates the principle of “non-refoulement,” which prohibits the forcible return or expulsion of refugees to places where their lives and freedoms could be threatened, and forbids the rejection of displaced persons that seek admission to safety at borders under all circumstances.

This has no doubt influenced the way in which the Lebanese government has coped with the substantial number of refugees within its borders. Till the present day, the GoL has failed to adopt any kind of policy to manage the refugee influx and has referred to them as “displaced persons” rather than refugees.

The GoL had initially upheld the open border policy and permitted the unrestricted entry of Syrians between 2011 and 2014. However, the substantial number of Syrian refugees entering Lebanon, with the threat of “tawteen” and the danger of upsetting the delicate sectarian balance, prompted the Lebanese government to adopt a restrictive approach to limit the number of Syrians entering Lebanon and obtaining legal residency and work permits. This has restricted the movement of Syrians out of fear of being detained or deported.

In 2015, the General Security Office (GSO) implemented harsh requirements and restrictions on residency, where residency permits are granted at the discretion of the GSO with a mandatory fee of $200, a fee that most Syrian refugees cannot afford since 68.5 percent of them live under the poverty line. The UNHCR estimated that this has led to a decrease in the number of Syrian refugees with residency permits from approximately 76.3 percent in 2014 to only 26 percent in 2017.

The Ministry of Labor (MoL) in Lebanon also issued Decree No. 1/218, which restricts the field of occupation of Syrian nationals to agriculture, construction, and environment (i.e. garbage and recycling). Later in 2017, the MoL issued Decision 1/49, which was nearly identical to the decision issued in 2015 but included a provision regarding the procedure of issuance and renewal of work permits for foreign workers. These decisions were issued under the pretext of protecting Lebanese workers.

The aforementioned issued decisions and policies signify a departure from the “open-door” policy maintained by Lebanon prior to the steady influx of refugees, where Syrian nationals were both subject to the same domestic law embodied in the Lebanese Labour Code that applied to foreigners, and benefited from the 1991 Fraternity, Cooperation and Coordination Treaty between the Lebanese Republic and the Syrian Arab Republic that granted both Syrian nationals and Lebanese nationals freedom of movement, freedom of residency and the right to work one another’s countries reciprocally. In practice, once a Syrian national in Lebanon obtains a residency permit, they can live and work in Lebanon indefinitely.

The actions undertaken by the GoL and its bodies thus violate both national law and bilateral treaties.

Over the years, numerous violations have been perpetrated against Syrians, such as violations in the form of torture, deaths in military custody, physical attacks, returns to Syria, widespread use of discriminatory curfews, and mass evictions.

In addition, the GoL had implemented policies over the past couple weeks that have been disconcerting; policies such as closing down Syrian-owned small businesses, a Ministry of Labor (MoL) run campaign to “combat the illegal foreign labor” of Syrians, and the demolition of approximately 5,000 informal tented settlements in Arsal rendering 15,000 Syrian refugee homeless. These problematic draconian policies and belligerent actions are no doubt one of many used as a part of a larger strategy to forcefully encourage Syrian refugees to return to a place where they fear for their lives.

Nevertheless, political figures have repeatedly made claims that the security situation and political solution in Syria are separate from the return of refugees so long as there are “safe zones.”

The urgency of the return of Syrian refugees as well as the establishment of “safe zones” all throughout Syria was popularized in 2017. The return of Syrian refugees continued to be the leading topic of contention and peaked in 2018 after Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil “retaliated” against the UNHCR for allegedly discouraging refugees from returning and calling for their integration into Lebanese host communities by suspending residency applications of all UNHCR staff. He made it a point to publicly tweet about the developments of his opposition towards the UNHCR; he tweeted that the UNHCR’s “acts against Lebanon’s policy of preventing naturalization and returning the displace to their homeland.” The “conspiracy” of permanently settling refugees has been one of the main components of anti-refugee rhetoric in Lebanon.

Whether the current political class is unceasingly propagating this false and hostile narrative and implementing belligerent policies to actually push for the return of refugees, or whether it is doing so to appease the angry mob of the exasperated Lebanese public, is beyond the scope of this article.

However, if the aim of the GoL is to aggressively initiate the large-scale return of Syrian refugees, it must conduct an assessment of the different economic scenarios that would take place if refugees were returned at the hasty pace it is insisting on.

Syrian Refugees’ Contributions to the Lebanese Economy

While Syrian refugees have impacted the Lebanese economy in various ways, such as additional pressure on an already exacerbated public infrastructure, primary healthcare system, educational system, waste-management system and power sector, they also contribute to the Lebanese economy is various ways.

There are numerous areas in the Lebanese economy that Syrian refugees have affected positively, such that their presence, the labor they perform, the rent they pay, and the sizable humanitarian financial aid that Lebanon receives annually contribute to the development of the economy.

Since 2013, Lebanon has received US$1 billion in donor aid annually. The humanitarian aid received is distributed to 76 different organizations, including WFP, UNHCR, UNRWA, UNICEF, and UNDP, to operate in Lebanon and provide relief and assistance to refugees in the form of basic assistance, food security, education, health, water, livelihood, protection, shelter, social security, and protection.

According to estimations made by the Refugees=Partners (R=P) project, Lebanon has received approximately $5.83 billion in humanitarian aid between 2013 and 2018.

The humanitarian aid has primarily been allocated to the World Food Program (WFP)’s electronic voucher program or e-card program to deliver some relief to both Syrian refugees and host communities alike. The WFP program provides the most vulnerable of Syrian refugees with cards containing $27 per person per month, and are only redeemable at 500 WFP-contracted Lebanese shops that profit from the presence of Syrian refugees.

This has led to the expansion of the stores and the creation of jobs to maintain the increase in demand for goods. As a result of this increased economic activity, the $5.83 billion actually translates into the injection of $9.33 billion into the Lebanese economy.

Aside from benefitting local host communities and the economy through consumption, Syrian refugees also contribute to local communities through rent. According to the UNHCR, UNICEF and WFP (2018), 81 percent of Syrian refugees pay rent at an average of $182. R=P estimates that Syrian refugee households make sizeable contributions in rent to landlords in local host communities as well as the Lebanese economy; they contribute a minimum of $383 million and a maximum of $530 million in rent annually.

Moreover, Syrian refugees are de facto consumers. Due to the rise in the demand and purchase of consumer goods, government revenue increased by $800 million between 2012 and 2016, a substantial portion of which is derived from indirect revenue from goods and services.

A 2018 scenario-based study found that the Syrian conflict and the subsequent influx of refugees will most likely lead to “profound changes to both the structure of the labor force and consumption and savings patterns in Lebanon, inducing shifts in the demand for goods and factors of production.”

One of the scenarios presented by the study determined that the overall decline in exports was “more than compensated” by the arrival of Syrian refugees in the sectors of agriculture, energy, communication, and transport.

Potential Economic Repercussions of Return

The presence of Syrian refugees over the past few years has no doubt affected structural changes in the Lebanese economy. However, contrary to the popular belief that Syrian refugees are negatively affecting the economy, their contributions to local economies and host communities, and the overall inflow of humanitarian aid cannot be ignored.

Prompting the hasty return of Syrian refugees may yield an even bleaker economic outcome and may have cataclysmic repercussions. Without the humanitarian aid and the consumption and labor output resulting from the presence Syrians in Lebanon, the economic growth will inevitably be hindered.

The large-scale return of refugees would also hurt local economies. The return of refugees would mean depriving both a substantial portion of landlords and the 500 WFP contracted shops in local host communities of their primary means of income, and local businesses would suffer from a shortage of low-skilled cheap labor that Syrian refugees provide.

Nevertheless, whether the benefits of the presence of Syrian refugees outweigh the adverse impacts cannot be determined in the absence of an extensive macroeconomic study on the impact of Syrian refugees.

Meanwhile, the current political class has overwhelmingly vilified Syrian refugees as the primary cause of the downturn of the Lebanese economy as a means to distract from the issues in Lebanon. The implementation of a comprehensive waste-management plan, air pollution, littering the Litani River, the increasing socioeconomic inequality and the mounting poverty have largely been ignored at the expense of the Lebanese population.

Before taking any further steps to implement the robust return of Syrian refugees, Lebanese political officials must conduct well-founded assessments concerning all aspects of the Lebanese economy, and the impact of both the Syrian conflict and Syrian refugees respectively.