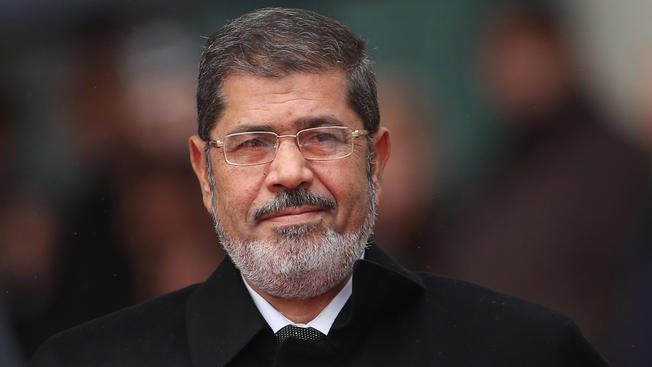

The death of former elected President Mohammad Morsi of Egypt should be seen as perhaps the single most iconic moment of modern Arab political history. For he represented everything that is good and bad about political authority and governance in the past century of Arab statehood. Yet his legacy will only be fully clarified in the decades ahead when the fate of the ongoing Arab uprisings also becomes clear.

Not surprisingly, it is in Egypt that his life and death capture the main lines of the modern Arab political struggles for stable statehood and citizenship. Three, in particular, stand out from 1952 until today, and they continue to shape the trajectories of power, the sources of political legitimacy, and the fate of entire societies. These are the rule of the armed forces, the opposition of the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamists, and the counter-revolutionary onslaught of conservative Arab monarchies against democratically-elected governments after the 2011 overthrow of the former Egyptian regime of Hosni Mubarak.

The first and most important of these has been the penchant for Arab military offices and allied security services since the 1950s to take over governments and economies, and mostly run them into decrepitude. The non-stop governance of Egypt under military rule since then, with only the 2012-13 interlude of the elected Morsi government, is not only a structural weakness of the Arab region that reveals itself widely in the form of shattered economies and many destroyed cities. It is also a growing threat because the heavy-handed nature of the rule of Field Marshall-turned-President Abdel Fattah Sisi since 2013 has added new layers of hard authoritarianism and abuses of ordinary citizens and civil society. The rule of the officers continues to harden, amazingly.

The second important symbolic dimension of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood Society is that they have consistently spearheaded two critical but failed aspects of modern Arab political life since the 1930s: the quest for good governance that promotes citizen rights and values and stable, prosperous societies, and open opposition to autocratic Arab governments, foreign colonial powers, and Israeli Zionism. Many other movements and forces have reared their heads and sought to govern well or to challenge dictatorships and family rule in Arab lands, but only the Muslim Brotherhood and its many offshoots, including a few militant ones, have consistently shown the courage, self-confidence, and persistence in their mission that explains why they have lasted so long and succeeded in a few instances, while all other opposition groups faded away.

Morsi was a symbol of the ultimate success that they had always sought: to govern the biggest Arab country, and to do so with the legitimate approval of the citizenry, which no other Arab government could boast —with the exception of Tunisia, where another Islamist party, Al-Nahda, was the big winner in the elections after the overthrow of the former regime.

Yet, tragically, Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have also broadly been political failures and amateurs. They repeatedly proved unable to use power effectively when they won it through elections or assumed it through appointments by the military, in countries like Egypt, Yemen, Kuwait, Sudan, Jordan and others. Morsi and his colleagues were neither prepared nor qualified for Egypt’s political incumbency in 2012, and it showed in their mismanagement of almost every sector of life and society. They had no idea how to mobilize the immense public support they enjoyed, nor how to respond to the military when it started working to overthrow them in 2013.

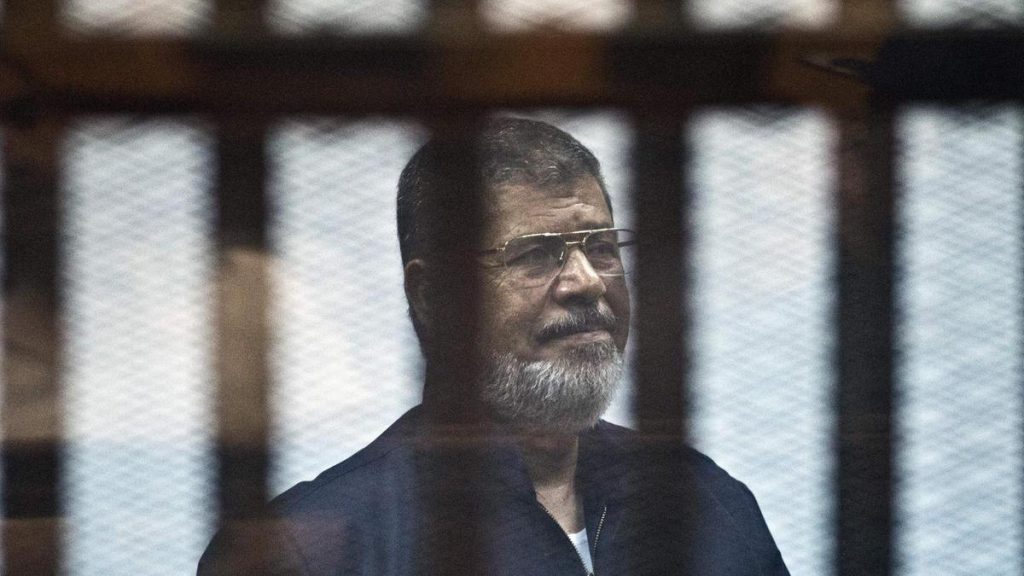

The third dimension of the political symbolism of Morsi’s life, overthrow, imprisonment, and death is what these reveal about the aggressive wave of neo-authoritarianism that now ravages more and more Arab societies. For it was the advent of the elected Morsi government in 2012 that so frightened the Egyptian generals, the deep state behind them, and their fellow travelers in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and caused them to join forces to overthrow Morsi and then make sure that nothing like that Islamist success ever happens again. These forces now smash the Muslim Brotherhood wherever they can, wipe out almost all active elements of independent civil society and media, and jail tens of thousands of citizens for their political views and for daring to speak their minds independently.

That resurgent Arab force of regressive conservatism and authoritarianism, with its popcorn machines in cinemas to keep the youth happy, now threatens many other “moderate” Arab societies that do not buy into either the Egyptian model of military rule or the Wahhabi-Saudi-Emirati model of states that manage the minds of their citizens alongside their malls and highways. The elected President Morsi mattered because he was the frightening reality —legitimate, populist, Islamist, and incumbent —in the biggest Arab country that scared these ultra-conservative officers and Gulf leaders who then unleashed the beasts of political regression.

Mohammad Morsi was much more significant than being a legitimately-elected president who was overthrown. His life and death tell a bigger tale: the continuing agony of Arab political cultures that insist on seeking a life of dignity, freedom, and prosperity, yet remain unable to do so in the face of the much stronger and moneyed forces of fear and authoritarianism.

The ongoing mass struggles for democratic pluralism and civilian authority in Algeria and Sudan, and regular demonstrations against government incompetence in half a dozen other Arab countries, remind us that Mohammad Morsi’s successes and failures —like Egypt and its people themselves— represent something much bigger that continues to play itself out today in most Arab countries.