The Lebanese Parliament denied a request to access declassified information in February 2018. In other words, the exact legislative body that passed the law on access to information stated that it has established no mechanism for information sharing. Ironically, the administrative office expressed willingness to submit a request to the parliament in consideration of abiding by the law that the parliament itself had passed.

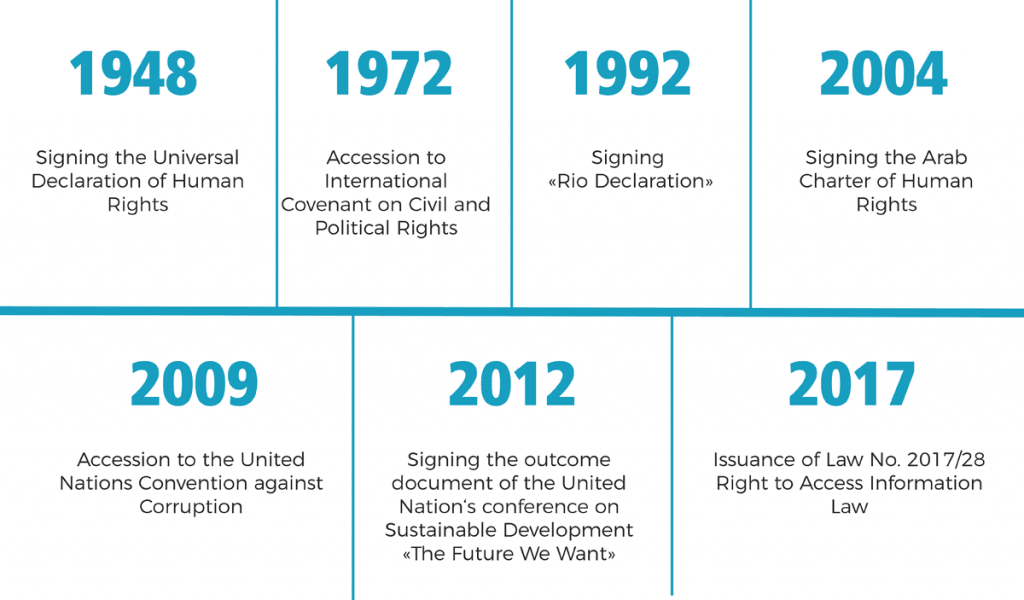

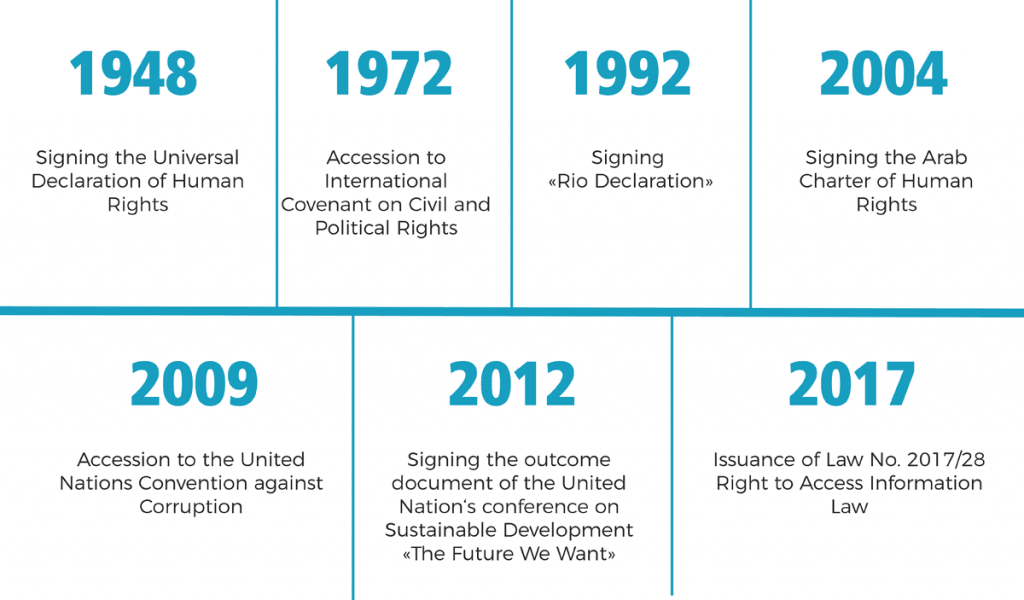

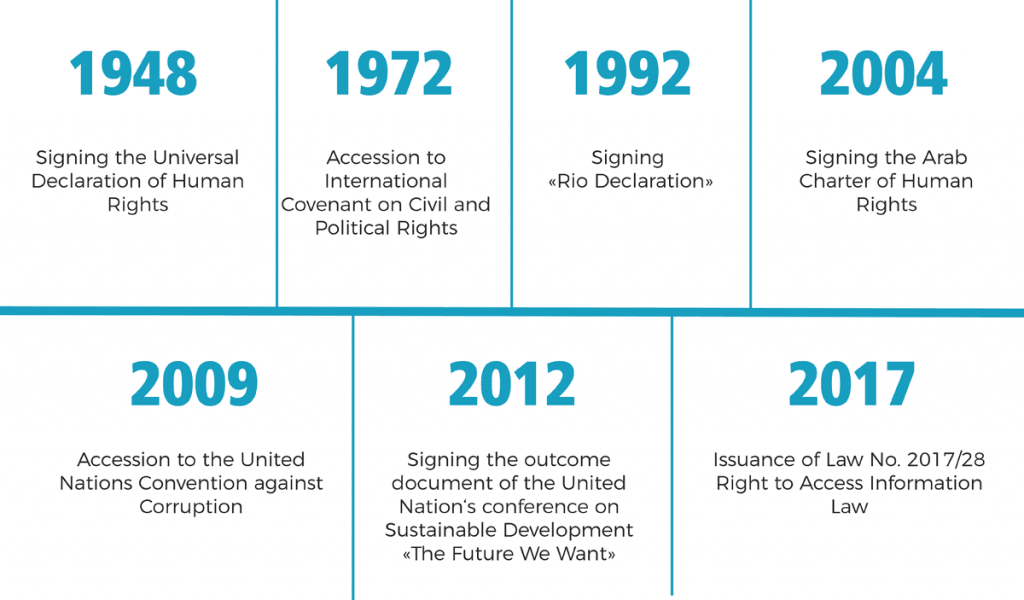

The Access to Information Law was ratified by the Lebanese Parliament in January 2017 after no less than eight years of being put on hold. The law provided that all key documents circulated in all governmental entities be accessible by the public through online channels or through an Information Officer assigned by the entity itself. This came about in order to ensure transparency, accountability and compliance with international standards of information sharing.

In March 2018, the Ministry of State for Anti-Corruption Affairs received a request for declassified documents. One might expect that a ministry dedicated to anti-corruption would happily adhere to transparency-related laws. However, upon the request, the ministry stated that “such documents don’t even exist at the Ministry for them to be published.” Additionally, the ministry provided that the 36 million LBP pouring into its budget every year are not enough to operate anything more than a Facebook page where citizens can enjoy regular updates on the ministry’s activities.

Upon the request, the ministry stated that “such documents don’t even exist at the Ministry for them to be published.”

These unfortunate facts were part of a comprehensive report published by the Gherbal Initiative in 2018 whereby the compliance –or lack thereof– of public bureaus to the information access law was put to test. The initiative submitted 133 requests for information from various Lebanese administrations and received no more than 34 responses, only 19 of which within the legal 15-day limit. The results were unsurprising, considering that the Lebanese governmental structure falls short of having adequate information management mechanisms. What becomes shockingly evident, however, is how unaware the general public has been when it comes to realizing the importance of accessing public information.

The initiative submitted 133 requests for information from various Lebanese administrations and received no more than 34 responses, only 19 of which within the legal 15-day limit.

The best example was set forth by Dr. Nadim El Khoury, a Lebanese dental surgeon, who has dedicated his time outside the clinic to engaging in civil society activism. El Khoury went to Facebook to talk about our constitutional right as citizens in accessing information. More specifically, he addressed the fact that members of parliament who have been elected by the people do not share with their electorate how they have voted on various laws that will ultimately affect the lives of this electorate.

The parliamentary sessions held on March 6 and 7 hosted the 128 members of parliament in a general assembly session to vote on 36 laws. The common form of voting in parliament is by a simple show of hands, whereby the Speaker takes a look to see if enough hands have been raised for the law to pass.

Much to our dismay, these votes are not recorded nor shared publicly, despite the fact that the provisions of the Access to Information Law allow any citizen to access the results of any parliamentary vote. As a result, El Khoury’s “MP Monitoring Initiative” was put into action. The initiative includes eight volunteers who perform a round of phone calls to members of parliament after every voting session to ask them about how they voted and why.

“Most citizens are afraid to call their MPs to monitor their performance in parliament,” wrote El Khoury, who found convincing people to take part in his initiative to be challenging, on Facebook.

The excuses that he heard ranged from “my family is a known supporter of this party” and “I can’t do it unless it’s anonymous as they might threaten my family’s work,” to “I am afraid to talk to a parliamentarian.” Others told him “that they just lost hope in the country and were tired of fighting.”

“Most citizens are afraid to call their MPs to monitor their performance in parliament.” –Nadim El Khoury

Further, in a conversation with the surgeon-slash-activist, he said that what drove him to take on this initiative was the fact that he was living in a country where he was witnessing corruption all around and he could either complain, or do something for the betterment of the situation.

When asked about where he sees this initiative going, he answered that this initiative has to lead to the establishment of an electronic voting mechanism whereby votes are automatically shared with the public through an online platform. This way, the electorate will be able to practice their rights of knowing how their representatives are shaping the country and, ultimately, hold them accountable when necessary.

The MP Monitoring Initiative is only one example of how access to information promises higher levels of transparency, accountability and, eventually, less corruption. The right to accessing information has already been set, which means that the legislative barriers standing between citizens and their right to information have been dissolved. What remains is the execution, whose responsibility lies on more than just the government and its public bureaus – as citizens, we share part of that responsibility.

The pathway to information has been open for citizens in order to enhance culpability, but the latter will not be possible without actively seeking this information and understanding how it affects our lives. Cultivating a population of informed citizens is a primary component of healthy state-building whereby individuals are brought closer to the political sphere and freed from the stigma that surrounds political activism. The lines that define what is political and what is not in the public sphere are blurry. Our involvement in political life is inevitable as long as we are active members of society. Therefore, our involvement ought to be one that brings about positive change.

Our involvement in political life is inevitable as long as we are active members of society. Therefore, our involvement ought to be one that brings about positive change.

Our disinterest, as Lebanese people, to access public information is due to the lack of civic education, lack of awareness on the importance of information and the overall sense that nothing is going to change. However, when we start realizing our right to know, our right to question and our right to object, we set ourselves on trajectory towards real democracy.