It was only two months ago that George Zreik self-immolated in front of his daughter’s private school in the Koura town of Bkeftine. The cab driver had been planning to transfer his daughter to a more affordable public school when the administration refused to provide him with her transfer documents. Having not paid tuition fees since 2015, and with no other solution in sight, Zreik set himself on fire and died a few days later in hospital.

Zreik’s death caused outrage nationwide, with many criticising the government for not providing affordable education and the ever-increasing tuition fees in private Lebanese education institutions.

After Zreik’s death, activists called for protests in front of the Ministry of Education. Described as a martyr, Zreik has been likened to Mohamed Bouazizi and others who have used self-immolation as an act of protest against the unbearable economic conditions in the Middle East.

While Zreik’s described martyrdom did reopen the discussion on high tuition fees in Lebanon, the issue remains overlooked by the concerned governmental officials and continues to be underrepresented in the Lebanese news media.

This is How Much You’re Paying For Your Private Education

As Zreik’s case signifies, there has been an increase in public school enrolment over the past few years. According to the Center for Educational Research and Development (CRDP), the number of students (both Lebanese and non-Lebanese) enrolled in public schools has increased from 943,763 in the 2011-2012 academic year to 1,065,490 in the 2016-2017 academic year. Besides the large influx of refugees into Lebanon, these numbers also reflect the financial difficulties families face to meet increasing tuition fees. The impact of education on the consumer price index increased by 5.4 percent in 2018, as published by the Central Administration for Statistics, meaning that the average consumer has spent 5.4 percent more on education services in the last year.

While the costs of education continue to rise, it is the increasing tuitions in higher education institutions that reflect the unrestricted manner in which private universities handle tuition on a yearly basis.

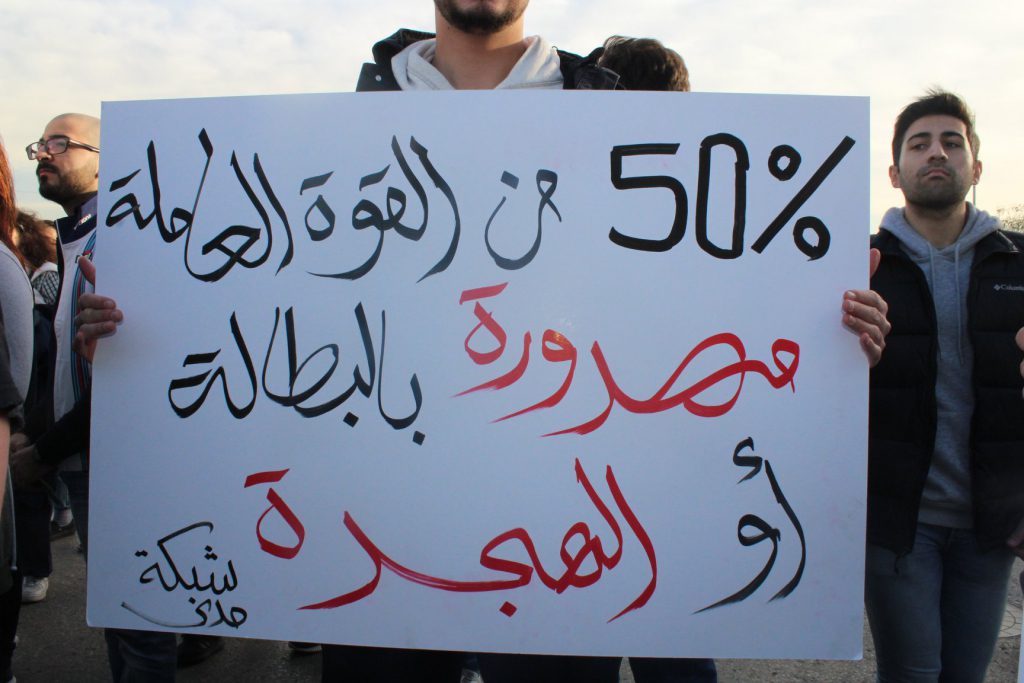

In response to the ever-increasing fees, youth network Mada emerged at the beginning of last year as a student activist group aiming to address the issue of unaffordable private education. The network launched the صوتي_عالي # (My Voice Is Loud) campaign, in which it called on students to sign a petition addressed to the Minister of Education. The petition called for a student contract to “safeguard the basic rights of university students from the very beginning of their academic careers.” The demands of the student contract included maintaining fixed tuition fees for ongoing students throughout their university stay, in addition to allowing students to engage in syndic work under a system of shared governance and an environment that supports freedom of speech.

Throughout Mada’s campaign, the network’s research team tracked the average increase in tuition fees in the top seven private universities in Lebanon between 2013 and 2017. The statistics provided for this four year period revealed that tuitions increased by 21.85 percent at Notre Dame University (NDU), 20.84 percent at Balamand University, 19.97 percent at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK), 18.91 percent at the Beirut Arab University (BAU), 16.79 percent at the American University of Beirut (AUB), 16.58 percent at the Lebanese American University (LAU), and 15.17 percent at Saint Joseph University (USJ).

This unrestricted increase in tuition fees is not monitored nor addressed by administrative representatives, often leading to students having to pay a larger amount each successive year during their education. It is essential at this point to take into consideration that the average student spends 4 years in university.

These expensive fees are unjustified and should raise questions on how and where students’ money is being spent.

In August of last year, Al Akhbar released an article documenting the salaries of the 23 highest earning administrative staff members at AUB, revealing an enormous $869,000 annual salary for the university’s president. A 2014 study conducted by Faculty United, an association of faculty members at AUB, revealed that administrators earned 19 percent higher on average, while professors earned 43 percent lower than average, compared to peer universities in the United States. These statistics, taken despite the fact that private universities like AUB do not publicise their budgets, raise questions regarding the legitimacy of increasing fees in the name of providing better education.

Going to the Lebanese University Means Being Neglected By The Government

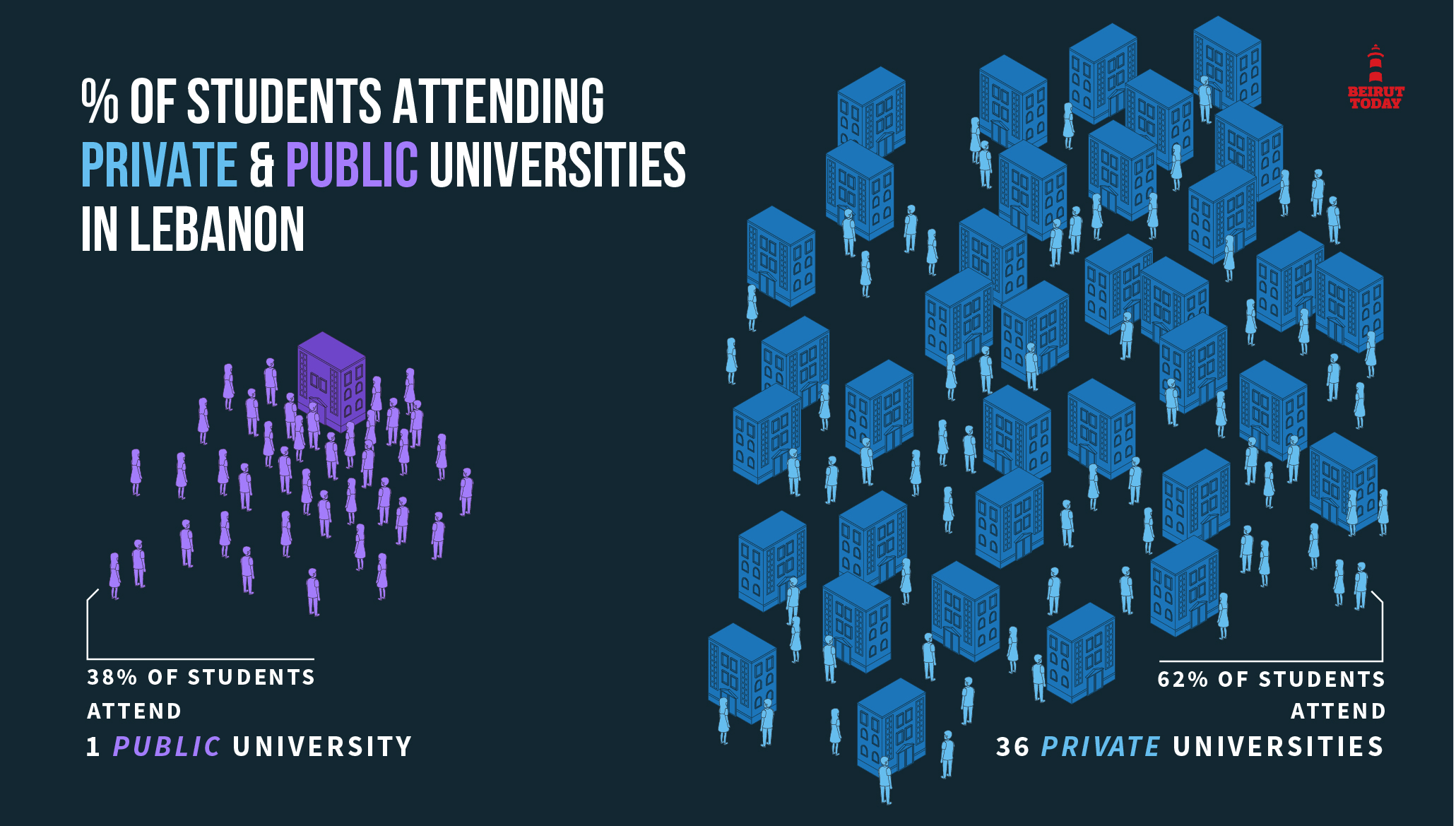

The lack of government regulation of these tuition increases goes back to the different sectarian interests embedded in universities and schools across Lebanon. There are currently 48 private higher education institutions –36 private universities, 9 technical and vocational institutes, and 3 institutions for religious studies– and one public university, as per the Ministry of Education website. According to a report by the CRDP, these private institutions held 124,851 students in the academic year of 2016-2017, whereas LU held 75,956 students.

With 38 percent of all enrolled university students attending Lebanon’s only public university, LU remains underfunded with no shared student government and elections.

While 62 percent of students are distributed among private higher education institutions, 45 percent of them attend the previously mentioned top seven, leaving 55 percent spread over 40 institutions, most of which obtained licenses after the end of the civil war in 1990.

The civil war left public educational institutions in shambles, and LU was neglected in the budget plans as Lebanon entered its reconstruction phase in the 1990s. Since then, the decline in the quality of public education has allowed for party officials to attain licenses to establish universities with explicit ties to political parties, and for private universities to increase tuition costs at alarming and unrestricted rates for the lack of any alternatives.

Public education continues to be overlooked as government expenditure on education amounted to 2.1 percent of GDP and 6.3 percent of public expenditure in 2015, a decrease from 2.4 percent of GDP and 7.7 percent of public expenditure in 2005, according to the previously mentioned review. The share of education in Lebanon’s public spending is lower than other Arab countries in the region such as Yemen, which spends approximately 6 percent of its GDP on public education.

Even If You’re Going To Private School, You Still Won’t Find A Job

As students face the decision between attending Lebanon’s only public university at the expense of not being able to engage in student government and receiving lower quality education, or attending a private university and paying excessive amounts of money, they are also tasked with finding a job after graduation.

However, as many students discover, attending an expensive private university does not guarantee finding work. According to a 2017 report by LBC based on statistics by Information International, 25 percent of the Lebanese population are unemployed, leaving about 325,000 to 350,000 of Lebanon’s 1.3 million labour force without work.

Youth unemployment in particular is at 40 percent, with 30,000 fresh graduates entering the labour force annually but only 7,000 to 10,000 available job openings to accommodate them.

The education sector in Lebanon is riddled with problems, and Zreik’s death came as a reminder of how dire the situation is for people who cannot keep up with increasing tuition fees. As the quality of public schooling continues to decline, private education institutions raise tuition fees with no justification. Couple the situation with the sectarian interests that stem from the different politically affiliated private universities across Lebanon, and what results is an education system with a ridiculously low return on investment and that caters to the well-connected and the well-moneyed.

There Are Students Fighting Back, But No One Is Listening

In a system where decline benefits governing officials, grassroots student movements are the only viable option. While the student movement continues to be stifled in universities across Lebanon, most notably by the absence of student elections in some institutions and the lack of student representation in administrative decisions in others, several efforts have been made in recent years to address the unaffordability of education.

Hundreds of AUB students protested in 2014 after a planned tuition hike of 9 percent, which was planned to take effect the successive academic year. The protests ended in the administration decreasing the increase in tuition to 3 percent, and this increase is still being implemented today. The AUB protests were preceded by a strike at LAU the prior year, which ended in the suspension of four students.

At a February 20 panel discussion titled “What About the Students? An Economic Model in Crisis!” held by the AUB Secular Club, MP Paula Yacoubian described education as the one of the very few opportunities to revive youth movements in Lebanon. She cited social media as an entry way for the youth into the political arena, a way to make their voices heard and their opinions considered when it comes to decision-making processes which affect them directly.

While Mada’s صوتي_عالي # campaign served as an example of the revival of the student movement on social media, the youth network’s contract was not met with any cooperation from the Ministry of Education. This is mostly due to the fact the current government was only announced in January of this year, after more than eight months of deadlock following last year’s parliamentary elections.

The potential of social media is slowly being recognised by independent actors working against the government’s narrative, as civil society groups continue to utilise online platforms to rally for different causes. As the future of the current government remains unclear, it is useful to remember Yacoubian’s words that “no one in Lebanon has the luxury of not being an activist.”