In the wake of the 43rd anniversary of the Lebanese Civil War, approximately 17,000 individuals are still disappeared. Despite numerous efforts made by civil society to provide relief and information to the families of the disappeared, the fate of much of them is still unknown. These efforts have ranged from Act for the Disappeared and the International Crescent of the Red Cross (ICRC)’s independent aid through psychosocial support and vigorous efforts at data collection to promoting and raising awareness on the proposed draft law for the disappeared.

This draft law was initially submitted in 2012 by the Committee of the Families of Kidnapped and Disappeared in Lebanon and Support of Lebanese in Detention and Exile, stipulates the establishment of an Institute or commission where “the Institute shall be an independent administrative body in charge of determining the fate of the missing and the forcibly disappeared.”

Although the families of the disappeared have been urging the government to pass the law as soon as possible, the parliament has been slow to respond to its ratification. However, the establishment of this commission would be hugely beneficial to these families. Beirut Today discussed the law with ICRC spokesperson Yara Khawaja.

“The main demand of the families of the missing is to pass this law,” said Khawaja, “And this will then establish a truth-worthy mechanism, with a humanitarian mandate, whose sole goal is to reveal the fate of the missing and to deliver answers to the families who have been waiting for more than 30 years.”

Over the years, previous attempts at establishing a commissions sanctioned by the Lebanese government were made to investigate the fate of the disappeared, but each attempt proved to be futile. Nevertheless, passing this new draft law can bring the families of the disappeared closure.

The History of National Commissions for the disappeared in Lebanon

Between 1975 and 1990, a police report said that it recorded 17,415 cases of enforced disappearances, with little other details being disclosed. This figure is disputed.

Needless to say, the families of the disappeared urged the government to undertake an investigation, and after years of rallying and protesting, the government established the first national commission in 2000. However, this investigation fell short of what the families demanded.

The 2000 six-month commission run by Lebanese security forces produced a meager two-page report that comprised of 2,096 cases of enforced disappearances. Another attempt was made in 2001, where the commission appeared to be more independent but was only tasked with investigating cases with proof that the individual may still be alive. It ran for 18-months, only looked into about 900 cases, and failed to produce a report.

Beirut Today also spoke to Nayla Geagea, a lawyer who worked on a draft law for the establishment of an Institute for the disappeared.

“All the commission that were established since 2000 did not manage to deliver a clear and concrete result, because they were all affiliated with the government,” said Geagea, who also elaborated that each of the previous commissions “had very limited resources, they didn’t have any kind of authority to take decisions and implement them, and they were completely hijacked by the political parties in Lebanon and as such were dysfunctional.”

When Beirut Today spoke to the Director of Act for the Disappeared, Justine Di Mayo Houry, she also echoed the same sentiment.

“It is important to highlight the past failed attempts at forming a commission to investigate the disappeared, where these commissions did not have any real power to conduct a real investigation and it hasn’t lead to any concrete result,” said Di Mayo Houry, discussing the need for this commission and the urgency of its establishment.

Both Geagea and Di Mayo Houry agree that the establishment of an independent commission or institute is crucial for the families. Geagea stated that the administrative and financial independency of this commission or body should be a requisite criterion for its establishment, where “we need an autonomous independent administrative authority that has all the judicial, administrative, and investigative prerogatives.”

In addition, this body should be given immunity against and be free of all types of political interference, provided with resources, and empowered by the law to make and implement its decisions. This is exactly what the draft law proposes.

The need and urgency for a national commission

According to Yara Khawaja, the families of the disappeared encounter a lot of legal trouble when it comes to the status of the disappeared. For example, if someone is disappeared, their legal status, as well as that of their families, may be compromised. They also encounter issues with legal assets, such as funds and property.

After conducting surveys and interviews with numerous families, Amnesty International also published a report in 2011 that describes the precise troubles that the families of the disappeared have faced and continue to face. The human rights NGO reported on a range of difficulties, including legal issues and the socioeconomic disadvantages that come with losing the breadwinner of the family, as well as the marginalization and legal disenfranchisement of female spouses whose husbands have been disappeared.

In addition, time is of the essence when it comes to the investigations for disappeared.

“It is urgent to establish this commission, because a lot of the information is being lost, such as information owned by former fighters who are growing old,” said Di Mayo Houry, “And a lot of sites of mass graves [that are located all throughout the Lebanese territory] are being destroyed because of construction, and it is very important to act.”

Act for the Disappeared primarily works in the protection of grave sites across the Lebanese territory.

ICRC specializes in gathering data from the families of the disappeared and collecting DNA, and more specifically biological reference samples for the identification of the disappeared. Khawaja also reiterated that it is essential to create the commission as soon as possible because the families of the disappeared are also passing away, and without them the identification is impossible. She also stressed that it is not the responsibility of the ICRC to reveal the fate of the disappeared to their families, rather it is the responsibility of the authorities to do so.

ICRC is currently “building the capacity” of expertise for when the commission is established, and Act for the Disappeared work to protect graves sites to preserve this information, and to then hand it over to the future commission.

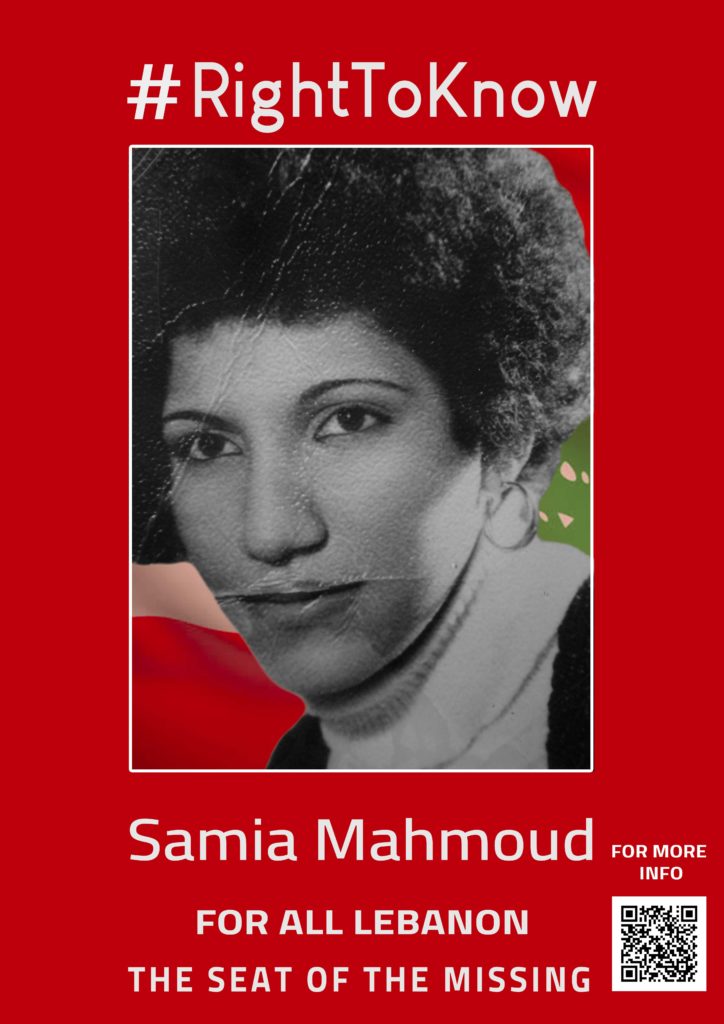

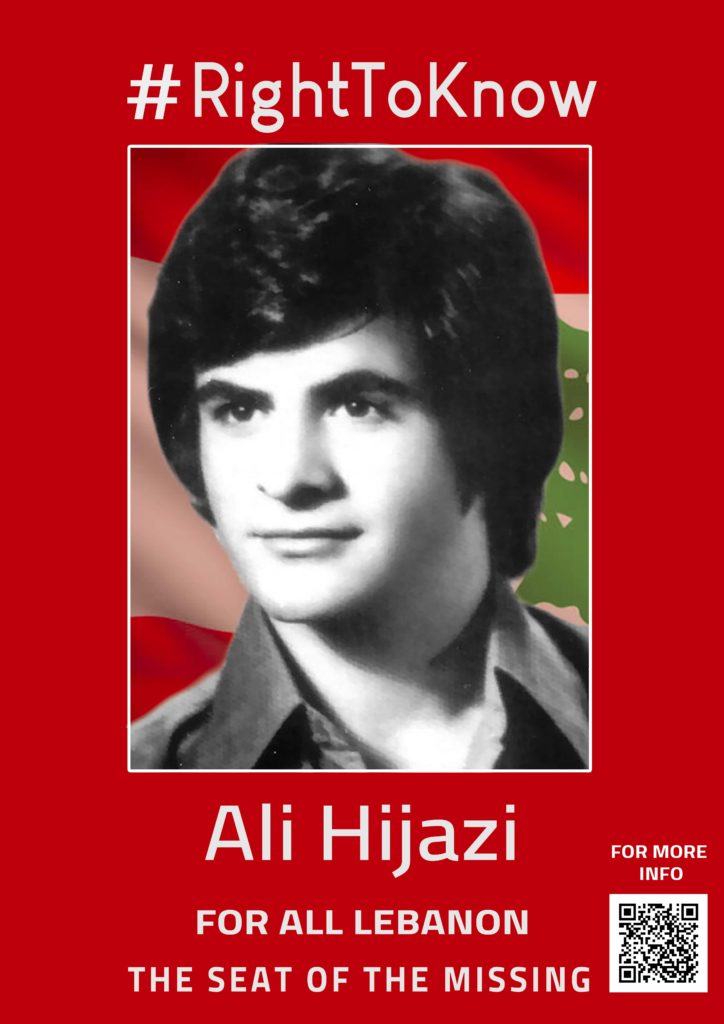

ICRC and Act for the Disappeared are working on campaigns to both raise awareness on the disappeared and on the draft law that can reveal their fate. ICRC’s campaign consists of a three-phase project, the first of which includes putting up six posters of symbolic candidates that are missing people around Beirut, as a statement during the parliamentary elections and a means to highlight the legal issues faced by the families of the disappeared.

Act for the Disappeared’s campaign also consists of placing figurines of people around Beirut in the specific location where someone was reportedly kidnapped.

What it means to have a national commission and the future

If the draft law for the establishment of an independent national commission to investigate the fate of the forcibly disappeared is passed “… it will finally give the families of the disappeared some closure, so that they will be able to bury their loved ones in dignity,” said Di Mayo Houry.

“What is lacking is the political will to pass the draft law”, stated Geagea. “Though the families of the disappeared even made a petition that many Members of Parliament (MPs) have signed and have committed to the cause, no one has been pushing for it.”

On April 10, 2018, the families of the disappeared met with President of the Republic of Lebanon Michel Aoun in the Baabda Palace. The president proposed that they form a committee to further assess the issue. However, the issue has already been assessed by enough ad hoc committees, with Geagea contending that a legal framework should be adopted through the draft law, and ratified and implemented as soon as possible.

The draft law is currently on the parliamentary agenda, but it requires a real political will to adopt the law, as Geagea stated. Hopefully, with the parliamentary elections coming up, the incoming MPs will push for the establishment of this commission to finally give the families of the disappeared some closure.

For more information on ICRC’s campaign please go to: https://www.icrc.org/en/missing-persons-lebanon

For information on Act for the Disappeared’s campaign please go to: http://www.actforthedisappeared.com/our-cause/17000-disappeared-lebanon