Since the onset of the Lebanese financial and economic crisis at the end of 2019, Syrian refugees have been one of the hardest communities. The lack of infrastructure in camps and the rapid deterioration of the Lebanese pound are among the many issues plaguing them at the moment, with period poverty being a core challenge to refugee women in specific.

The price of sanitary pads, for example, has increased by more than 500 percent since the beginning of the crisis, which has been termed one of the world’s worst financial crises since the 1850s.

“When we first started in May 2020, the menstruation kit used to cost LBP 15,000 and it used to contain period pads, pantyliners, and wipes,” said Line Masri, one of the co-founders of Dawrati.

The NGO collects donations of disposable menstrual products and distributes them to communities that need them, including refugee women in Lebanon.

“Today, if I buy pads from the supplier, my menstruation kit costs me between LBP 45,000 and 50,000 and it only contains period pads,” she said. “We are no longer giving out pantyliners or wipes anymore. The price tripled and I had to remove two products from my menstruation kit.”

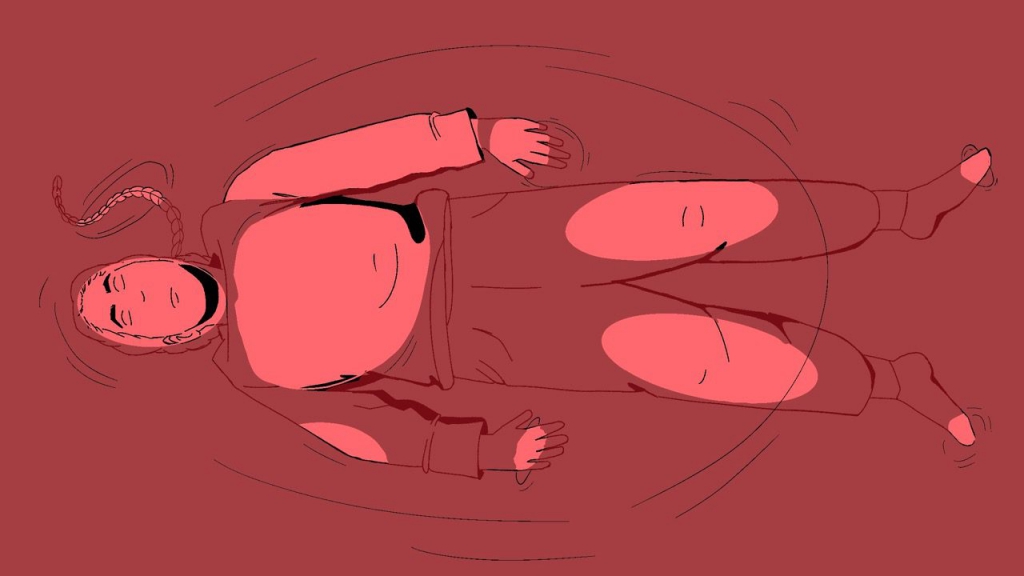

As defined by the UNHCR, period poverty not only includes the inability to purchase menstrual sanitary products, but also “long distances to a private toilet, little to no electricity across camps, no locks on toilet doors, sexual and gender-based violence (GBV).”

The state of menstrual health in Lebanon

Almost 80 percent of the Lebanese population has sunk below the poverty line, largely rendering large portions of the Syrian refugee community unable to afford disposable sanitary products, or even affordable alternatives. Not only so, but a lack of awareness among refugee communities largely contributes to the issues, as there remains many taboos and hesitation concerning sanitary products like period cups.

In August 2020, Plan International found that 35 percent of adolescent girls do not have physical access to get menstrual pads. Out of that figure, 69 percent are Syrian adolescent girls and 31 percent are Lebanese.

““While findings are shocking across populations, our assessment clearly shows Syrian refugee girls are being hit the hardest in the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Colin Lee, Plan International’s Director for the Middle East said.

“Among 35% of adolescent girls who reported they do not have access to menstrual supplies, an overwhelming two-thirds were Syrian refugee girls,” said Lee. “Not just access, affordability is another issue that girls are grappling with. 66% of adolescent girls reported they do not have the financial means to buy hygiene pads. More than half of these were Syrian refugees.”

According to Dawrati, 50 percent of women suffering from period poverty are using newspapers, old rags or toilet paper during their menstruation. In substituting disposable menstrual products for newspapers and other alternatives, refugees are subjecting themselves to a series of health concerns, including life-threatening infections.

Those who can still afford pads opt for cheaper ones with a poorer quality that may cause irritation, foul smells, and painful rashes.

Aid for Syrian and Lebanese women

As a result of these challenges, many initiatives and NGOs have come up in response. Dawrati’s work is not limited to Lebanese women, Syrian women may benefit from their collection and distribution of donated disposable menstrual products.

“When working with refugees, we mainly work with an NGO called Malaak. They are based in Amman, and we distribute through them for both refugees and Lebanese women,” said Masri.

Days for Girls (DFG) is another group working on menstrual health in Lebanon. It “increases access to menstrual care and attempts to shatter stigma around periods by encouraging girls and women to speak freely about menstruation without shame.”

Menstruation and sexuality largely remain taboo topics in the Arab world, and women are often shamed or subject to embarrassment when discussing the topic.

DFG also provides Syrian women and young girls with “access to sanitary menstrual products and a means of generating income by teaching these women how to make their own pads in an enterprise programme.” Among their target audience is the Chatila refugee camp in Beirut.

Yet these initiatives are incapable of fully bridging the camp if the government remains negligent on this issue. When the government first introduced the subsidy plan in early 2020, sanitary products were not amongst the list of subsidized basic necessities despite the fact that other less important items were included—such as men’s razors. This is a large indicator of gender inequity in Lebanon.