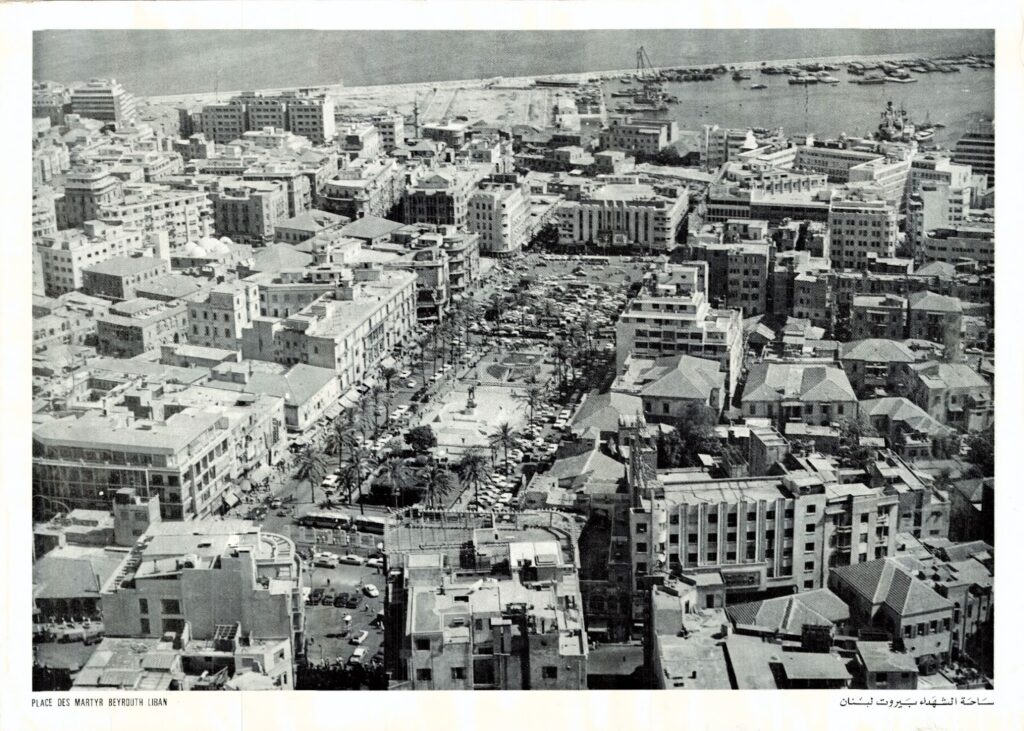

In my research for this piece, I was faced with a crippling dilemma. Coming into it, I was simply consumed by a thirst to hear from individuals who had experiences of going to the cinema in 1960s Beirut. I wanted to transport myself into the body of a 17 year old running to Martyr’s square after the school bell on a Wednesday. Stretching my gaze above fields of wandering heads in the ‘Balad’, now called Downtown, I would glimpse my friends ushering me with flailing arms to the front of cinema Rivolli. I would dig through the grainy depths of my pockets to find half a lira; enough for a falafel sandwich to cartoonishly swell my cheeks as I scan the erotic posters on each cinema entrance. “Come see this movie! The guns never run out of ammunition and the hero doesn’t die!” men would preach, a bit too closely sometimes.

After interviewing cinema enthusiasts from this period like vintage Lebanese movie poster collector and archivist Abboudi Abou Jaoudi and other avid ex-cinema-goers, my fascination with the way people navigated that arena and the ways the industry operated expanded tremendously. “Malla Ayyam,” or “those were the days,” elders would sigh in desolate nostalgia. On some people’s tongues, the period in history sounded like a sensational fever-dream. But the more reading and scavenging I did, the more I realized that the verbal recollections of the so-called “Lebanese Golden Era” were an ultimate source to remembering the romantic, but certainly not to remembering the real.

Abou Jaoudi’s father distributed and programmed films for the largest cinema in Bourj Hammoud, placing him in the center of all the cinema commotion. He spent his early life hopping from one theatre to the next in the bustling city and often organized movie reels with his father.

“Production houses [that established offices in Beirut] like 20th Century Fox, Paramount, Warner Bros, [and more] received only one copy of a film [to be screened in one theatre for a week on average]” the archivist told Beirut Today. Of course, if the film proves successful, the screening period can exceed years, like with ‘The Sound of Music’ or ‘Waladi’, a Hindi melodrama which crazed the nation’s film discourse.

“One reel of film,”which likened to the size of a car’s wheel, “carried around 10 minutes,” Abou Jaoudi explained. Projectors required someone to disengage one reel when it was done and quickly replace it with another one to continue the film seamlessly. “It takes about nine to 12 reels to finish a full fledged feature movie.”

(Left: Abboudi Abou Jaoudi holding a film reel wheel) (Right: Around 10 minutes of film)

Sometimes, cinemas in the ‘Balad’ and in Hamra would agree to screen the same movie at around the same time. With only one copy of the film in the country, the loophole is hilarious.

“Let’s say cinema Empir [in the Balad] would schedule to start projecting the film at 3:00, while cinema Saroulla [in Hamra] scheduled at 3:15. Once one reel finished playing in cinema Empir, a reel delivery man had five minutes to take that reel to Hamra street on a motorbike to be used in Saroulla,” added Abou Jaoudi.

The delivery man would end up rushing back and forth between the two cinemas around nine times until the movie finished playing in both theatres, and the number of deliveries climbed up to 12 if it was a Bollywood film. This is not to mention that the movie would premier throughout the day for at least a week.

The Lebanese theme of hyper fixating on maximizing commerce was not only exploitative of the delivery man, but to the entire country’s collective imagination, conditions of life, and creative agency in film-making and production. With the cinema scene becoming a core catalyst for tourism and the regional economy, puppeteers of the industry typically allocated budgets for films calculated for mass success. This facilitated the rise of template Egyptian romantic comedies which dwindle around the few similar events, homes, archetypes.

Burdened by the incessant need to sell, authentic representation was a challenge, especially within the Lebanese film industry. The local dialect was considered a film niche, forcing Lebanese filmmakers to produce in the Egyptian dialect or co-produce with Egyptian producers to appeal to most. Additionally, particular government censorship laws inhibited the tackling of stigmatized national conversations.

Giovanni Vimercati’s thesis, Port of Entry: Towards a Political Economy of Cinema in Lebanon, mentions that, “the country on film was often reduced to the hotel district in Beirut, the St. George bay, the Casino du Liban and a few panoramic shots of Baalbeck, Mount Lebanon or Byblos. Poverty, emigration and hardship were nowhere to be seen,” a strategy employed to propagate Lebanon’s “Switzerland of the Middle East” slogan.

This phrase, through the restless sanitizing and monitoring of permissible Lebanese content, was even internalized by the people in the peripheries of Akkar and Jabal Amel. According to researcher Karim Merhej’s piece, Paradise Lost? The Myth of Lebanon’s Golden Era, many of those people were earning below 1,200 or 2,500 L.L. annually, barely affording to buy basic necessities.

“There were 370 cinemas in Lebanon,” Abou Jaoudi said. 27 based in Beirut, and at least one or two set in small rural villages. Aley, a town in the center of mount Lebanon hosted 7 cinemas, and the smaller neighboring villages that were a minute’s stroll away possessed their own too. While cinemas were accessible to the peripheries, the cinema experience varied monumentally. “The villages only screened movies for the purpose of entertainment and fun,” says Abou Jaoudi, critically.

Films which posed hard social questions or critical interpretations to life were entirely absent from the rural cinema scene; enacting the still-standing national trope of centralizing intellectualism in the city.

“Watch out! He’s behind you!,” adolescents shouted at the screen, riling the arena into quaking laughter. Cinema in the more secluded areas typically meant watching a movie with relatives and friends.

It was even rumored that in the poorer areas of Beirut like the Msaytbe, aromas of boiling tomato sauce from pots of stuffed zucchini would permeate inside the theatre. Women cooked and served amidst the movie, their only source of light emanating from the shaking projector screen.

“I cried more than the protagonist when I watched that film,” a 75 year old woman from Abadiyeh says about her first time in Salwa, the local cinema. “I spent a month living as [the heroine in the 1950s Hindi movie ‘Ibada’],” she chuckles.

The boom of cinemas in Lebanon marked the kickstarting of an engine to a globalized, laissez faire economy destined to run out of fuel. Following the 1926 constitution within which politician and banker Michel Chiha fabricated an economic model heavily dependent on the constant injection of foreign capital, the ultra consumerist culture of cinemas, shopping, mercantile services, and glamour ensued. Despite the fact that only a tiny fraction of the population could afford to experience Lebanon like a postcard, photos of people frothed around cinema entrances in fancy updos while polished Peugeots grooved over pristine streets are what stain national memory.

(Source: Abboudi Abou Jaoudi’s collection)

My dilemma about the angle of this piece started after submerging myself into the colourful cinematic world of Abboudi Abou Jaoudi’s vintage poster store, listening to all the fascinating nostalgic memories and details of that scene, and then walking out into the dust-ridden and rundown Hamra street of today. Immediately I began to fantisize about what it would have been like, walking to Piccadilly theatre, smells of Arabic coffee and freshly baked Manoushe dough battling for prominence on every square meter, and spotting Egyptian movie stars who’d come to watch their films premier lounging in the sidewalk cafes. The image began to fade as my eyes were forced to the ground, scouring for crooked tiles and holes to dodge my step.

Today will become yesterday, and tomorrow all the same. The distressed reality of Lebanon today is at its core tied to the systems which facilitated the 1950’s ‘Paris of the Middle East’. Do I critique the neoliberal, centralist structures which orchestrated the cinema scene and stripped it from any profound sentiment? Or do I lend a vivid spectacle into the riveting and charming memories of cinema in Beirut and risk idealizing an era which contributed to our economic demise?