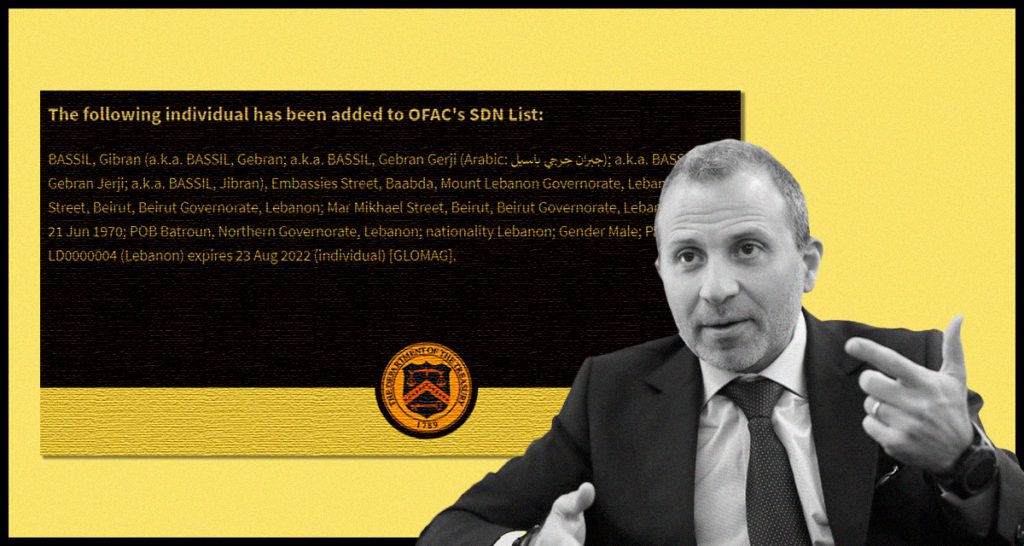

The United States recently imposed sanctions on Lebanese politician Gebran Bassil, president of the Free Patriotic Movement and central ally to Hezbollah.

The sanctions on Bassil came as one of the final decisions taken by the Trump administration prior to the outgoing US president’s electoral loss against Joe Biden.

In the statement announcing the sanctions, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo said Bassil was being sanctioned under the global Magnitsky Act for being “notorious for corruption.” Pompeo also said the FPM leader is aiding Hezbollah’s “destabilizing activities.”

Under the sanctions, Bassil is barred from entering the US and has had his assets in the country frozen. “Sanctions have not scared me nor promises tempted me,” Bassil tweeted following the announcement.

His formal response to the imposition came in a press conference on Sunday, where he said discussions of sanctions by the US began in 2018. According to Bassil, the US government asked the Free Patriotic Movement to cut ties with Hezbollah.

“What was required of me was to immediately sever the relationship with Hezbollah and three other points –not a word about corruption,” he said. “My natural quick reaction was to reject this issue because it violates a basic principle of the FPM, which is its refusal to take instructions from any foreign country.”

On the other hand, US Ambassador Dorothy Shea said that Bassil expressed his willingness to cut ties with Hezbollah during one of their exchanges.

“Mr. Bassil may think that it serves his cause to selectively leak information about our exchanges, taken out of context,” the Ambassador said in a circulating video statement. “That’s not how I normally operate, but I’ll put one thing out there: He himself expressed willingness to break with Hezbollah, on certain conditions.”

Why sanction Bassil now?

US Ambassador Dorothy Shea denied any relation between the sanctions and their coinciding with the US elections.

“Mr. Bassil seems to want to project intent onto our leaders,” said Shea. “The designation had nothing to do with the US elections. The package had simply reached a point where it was ready to be implemented.”

Despite that statement, the Trump administration’s actions over the past few months –and reported plans for its final 10 weeks in power– imply otherwise. Donald Trump is pushing for one final attempt to apply “maximum pressure” on Iran.

If the US were truly concerned with Bassil’s corruption and the will of the Lebanese people, the Trump administration would have imposed these sanctions at any other point since the start of the October 17 revolution in 2019. The FPM leader earned himself the title of the “most hated Lebanese man” during nationwide protests.

Instead, the intentions behind Bassil’s sanctions should be taken with a grain of salt –being the latest in a series of aggressive decisions taken by the US against Iran.

Sanctioning Bassil adds pressure on FPM’s political ally Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed party in Lebanon that the US considers to be a “terrorist group.” Hezbollah is a central player in Lebanon’s sectarian political system, holding key governmental positions and allies within the country.

Last month, the Iranian Petroleum Minister, Bijan Zanganeh, was sanctioned by the US for charges relating to terrorism –along with the petroleum ministry, the National Iranian Oil Company and the National Iranian Tanker Company. The Iranian ambassador to Baghdad was also sanctioned for destabilizing Iraq. In Lebanon, the US sanctioned ex-Lebanese ministers Hassan Khalil and Youssef Fenianos back in September.

Also in September, the United States attempted to reimpose UN sanctions on Iran through a “snapback” process –which allows any relevant party to begin a process that returns UN sanctions on Iran if the country is not complying with the 2015 nuclear deal.

13 of the 15 UN Security Council member countries rejected Washington’s authority in executing such a decision since Trump abandoned the 2015 deal, and have not taken the statement any further.

One European diplomat told AFP that the Americans will “pretend that they have activated the snapback and that therefore the sanctions are back up and running [but] this action will have no legal foundation [and] cannot have legal consequences.”

This week, US news website Axios cited two anonymous Israeli officials who reported that the Trump administration will announce even more sanctions on Iran before president-elect Biden assumes office on January 20, 2021

“The goal is to slap as many sanctions as possible on Iran until January 20,” said the source. A US envoy arrived in Israel on Sunday to discuss the plans which, according to Axios, will also be implemented in coordination with Washington’s Arab allies –most notably, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Analysts expect Joe Biden to ease relations with Iran and revive the 2015 Iran nuclear deal which he helped negotiate when Barack Obama was president, but Trump’s decisions now may make the president-elect’s attempt more difficult. When sanctions are placed by Washington, their justifying details make them difficult for any US authority figure to lift.

Bassil’s sanctions, which could have been designated any time over the past two years given his track record, are a small part of a bigger game.

The sanctions mean more delays for the Lebanese government

Disputes over ministries have stalled the formation of the new Lebanese government, led by Prime Minister-elect Saad Hariri, for weeks on end.

Hariri, forced to resign by anti-corruption protesters over a year ago only to return to his post last month, expressed his desire to form a new government based on non-partisan competencies to lead Lebanon out of the worst economic crisis it has experienced in decades.

Gebran Bassil heads the largest bloc in Parliament, the 24-member Strong Lebanon bloc. The Washington sanctions ultimately threw another wrench into the formation of the Lebanese government.

While the US sanctions were meant to take power away from Hezbollah and drive the militant-group out of the Lebanese government, they will more likely push Bassil to seek greater involvement for the Free Patriotic Movement in the next cabinet to protect his political standing.

Mustafa Alloush, former MP and member of Hariri’s Future Movement, told Arab News that Bassil is “the main obstacle to forming a government” because he “has returned to his old demands.”

Bassil, in the same speech he addressed the US sanctions in, outlined different conditions for the formation of the cabinet.

“The Cabinet formation must be based on three pillars,” he said. “The first of which is the number of ministers. A minister must not be allotted two portfolios, otherwise this matter will undermine the principle of specialization and is a failed project for any minister with two portfolios.”

For weeks, the same political figures who have led the country for the past 30 years have disputed regarding which party gets to lead different public-services ministries.

The US sanctions have also likely put a dent into Bassil’s possible aspiration to succeed his father-in-law, President Michel Aoun, as the next Lebanese president. International US allies are unlikely to support Lebanon when someone blacklisted by Washington is leading the country.

Meanwhile, Lebanon desperately needs aid to tackle its multi-pronged crises: The Beirut port explosion which destroyed swathes of the capital, the COVID-19 outbreak which has forced businesses to shut down, and the dollar crisis which was triggered by years of public corruption and mismanagement.