The unjust and heart-wrenching murder of George Floyd at the hands –or more like the knee– of a police officer sparked a wave of protests in support of Black Lives Matter.

It didn’t take long for many Lebanese people to join in on the online rage, appalled by the United States’ systemic racism. Stories and posts in solidarity with the movement flooded social media.

Many Lebanese were suddenly so ready to insert themselves in the conversation to discuss and criticize the longstanding systemic racism in the United States, as long as fingers were not pointed at Lebanon’s racist practices.

When flooded with so many compassionate messages about the Black Lives Matter movement in a country where racism continues to reveal itself in countless ways, confusion is inevitable. One can’t help but wonder: What understanding of anti-racism do some people have?

How can their sudden staunch rejection of racism in the US be taken seriously when behind the screen, it’s the same people degrading and disrespecting the people of color working for them?

Migrant domestic workers are frequently referred to with a demeaning “el sirlakiye li 3ande,” which translates to “the Sri Lankan I have” –often used as a universal term regardless of their actual nationality. This is indicative of an ongoing dehumanization and condescension of these workers by their employers.

In Lebanon, racism makes itself apparent in many different ways, one of which is language –a foundation that holds the power to shape a person’s understandings and belief systems. When racism is engrained in the colloquial language used by many Lebanese, there is no doubt that behaviors and perceptions of racism will continue to be molded and reinforced.

To this day, some people still use the word “3abed,” which literally translates to “slave,” to refer to black people despite being aware of its very racist essence.

OTV once aired an ad in which the word “zounouj” –in English, the ethnic slur “nigger”– was so casually used to project anti-black sentiments.

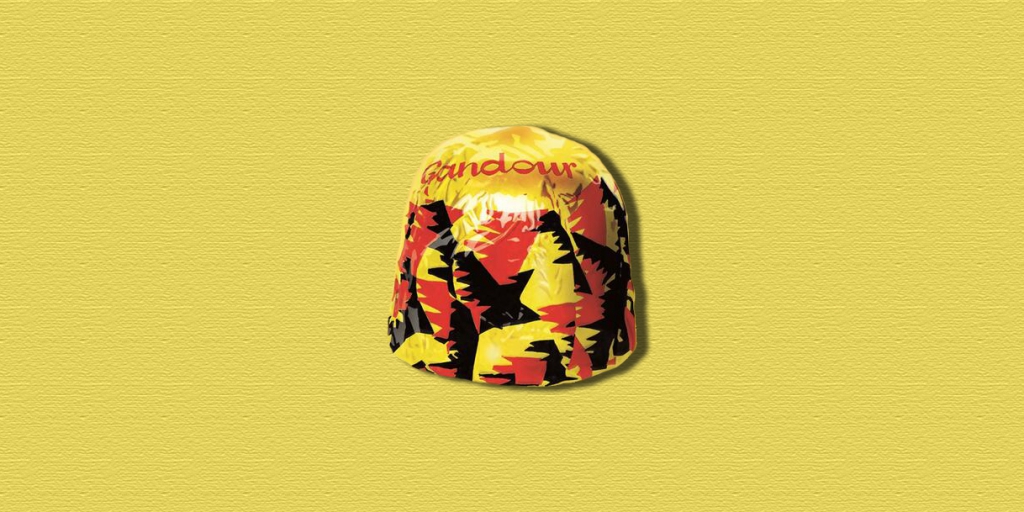

Oftentimes, one can still encounter people that call Gandour’s cream-filled chocolate “Ras el 3abed” (“slave’s head”) instead of “Tarboush” (fez). Once called out on their mistake, some are annoyed and others respond with “it’s the same thing,” refusing to both be held accountable for their choice of words and recognize the racism that this language perpetuates.

On another level beyond language, the Kafala system persists. Practiced since the 1950s, this epitome of neoslavery is built on racist beliefs and practices. Its similarly longstanding history is not one that many Lebanese are as ready to discuss and fight. This is despite the constant circulation of news about the maltreatment and death of migrant domestic workers at the hands of the system often compared to “modern-day slavery.”

Last week, Ethiopian domestic workers were cold-heartedly dumped in front of the Ethiopian Consulate in Hazmieh, left to sleep on the streets before some of them were taken to a hotel in Ain El Mreisseh. Today, many more are stranded on the streets as their employers continue to abandon them amidst an exacerbating economic crisis.

Three months ago, Faustina Tay’s body was found dead and her reported “suicide” was superficially followed and investigated before being once again being cast aside.

Why is it that many of the Lebanese people who are so enraged by the murder of George Floyd are the same ones who stay silent and unmoved in the face of these atrocities? What about the domestic workers who live in their country, where their deaths are brushed off and their murderers go on freely living their lives? Do their deaths mean nothing simply because they don’t gain similar international coverage?

Applauding the anti-racism movement happening in the US is indeed essential but it means nothing if one continues to stay silent about the rampant racism in Lebanon. It means nothing if one is not reflecting on their own actions and on the ways in which they might be reinforcing a racist system that feeds off of the most vulnerable.

Anti-racism is not only about the tolerance of racial minorities. It means that we break the silence, engage in uncomfortable conversations, call out racist comments and educate those around us. Most importantly, it means that we actively fight for the rights of these minorities.

While it is important to celebrate the Black Lives Matter protests in the US, let’s first take a look at how we can dismantle the very rampant racism in our country. Let’s make sure that we take our efforts beyond the tricky realm of the online world so we don’t fall into a mirage of slacktivism.