It’s a rare occasion for my dad to invite me to the movies; to go to the movies at 10:30 a.m. has downright never happened.

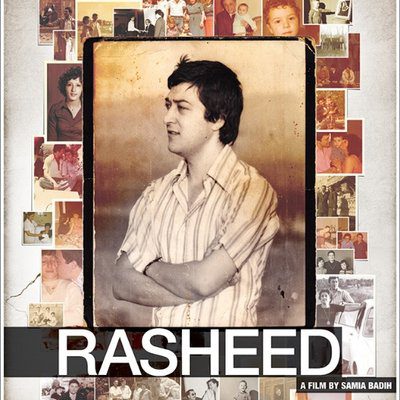

It’s a special occasion meant to unite the many in our hometown. A private screening of Saida’s own Samia Badih’s documentary, Rasheed (2017). This wasn’t just any documentary. The man featured is one of the 175,000 people killed during Lebanon’s 1975-1990 Civil War. The theatre audience was mainly comprised of family, friends, schoolmates, and neighbors.

Saida witnessed major losses during the civil war. Rasheed, alongside his wife and two kids, were among them. The Lebanese war is not a favorable topic of discussion; it happened, it’s done! Denial lives on. Pictures of martyrs are hung everywhere, but the post-war generation rarely knows much about its town and country’s history which is relatively tragic.

Samia, a director and previous journalist, is a practical exemplar of the denial being spoken of. Born three years after her uncle passed away, her family’s death was a topic seldom discussed. Growing up, Samia would hear snippets about her uncle within the neighborhoods of Saida; clearly, he was a man of prominence in the society, yet he remained a ghost-like character in her household.

In this feature documentary, Samia Badih goes on a quest to meet her uncle; in the process, she unravels the reality of the Israeli occupation on Saida and Lebanon. Stories that many have heard pieces of whilst growing up, are plastered on a screen–forcing those who lived the events of 1982 and those who heard of them to face the history in disguise.

Who was Rasheed?

Badih follows the life and death of Rasheed Broum who was killed in an air strike during the Israeli invasion of South Lebanon in 1982. The beauty of this documentary lies in how the story is being narrated. There is no one angle; Rasheed’s role as a political and social activist is not the highlight. The war is also not a main focus. Instead, what is being portrayed is the story of a person, just like any other. A person who had typical friends, who fell in love at some point, who started a family, who believed in certain ideals and who stood up for them. Rasheed is presented a charismatic, easy-going person. Like many others, his life was terminated too soon at the age of 29.

It took 30 years for his story to be told loud and clear.

Why does Rasheed’s story matter?

As I sat in that semi-filled theater next to the men and women of Rasheed’s youth, I couldn’t help but feel the heaviness of the room. These people knew Rasheed. These people could have been Rasheed. My father, my mother, and my sister could all have been Rasheed. There was a discomfort in the theater and as soon as the film was over, people quickly left.

What I came to realize, furthermore,is the extent of unresolved trauma residing in my town. The people that survived the war carry its weight with them wherever they go. Friends had to bury friends, neighbors had to search for corpses in burnt buildings, and families had to let go of fathers they’ve lost. Yet, these people do not truly delve into these issues. They do not seek help. Instead, they keep all the pain and suffering buried inside along with the entirety of this ideally grand history.

No matter how much the post-war generation reads or hears narratives about the war, it’s never the same as living it. With the martyr square placed front and center within Saida, and posters of those gone missing and killed during the war hanging around, one cannot help but feel like we’re living in a ghost town. Indeed, the same can be said about several other cities and villages in Lebanon.

Giving the dead names will bring them back to life

In the documentary, Badih refers to Robert Fisk who says: “Giving the dead names brings them back to life.” By remembering Rasheed, Badih was able to bring her uncle back to life. She was also able to bring back the memories of the war to those who lived it, and to spark curiosity to know more in those who did not live through it.

Recalling the war that our country underwent is genuinely important; people need to break the silence and cope with its travesties to learn from and reflect on it.