Lebanese-British journalist Zahra Hankir was covering waves of protests across the Middle East and North Africa for Bloomberg in London. Like many, she was inspired by the developments unfolding across the region, but baffled by the minimal attention given to the Arab women reporting on them.

“Western correspondents who were seen as experts were unsurprisingly commanding the international media narrative,” she told Beirut Today. “Yet, I felt at the time that local, Arab women were doing incredible work on the ground as they covered their home countries and weren’t garnering nearly as much attention.”

Hankir didn’t see these women as your usual war reporters or correspondents.

“They were natives who were telling different, more personal stories about war and its devastating consequences,” she said. “[They] were also facing steep and unique challenges that their Western counterparts were not.”

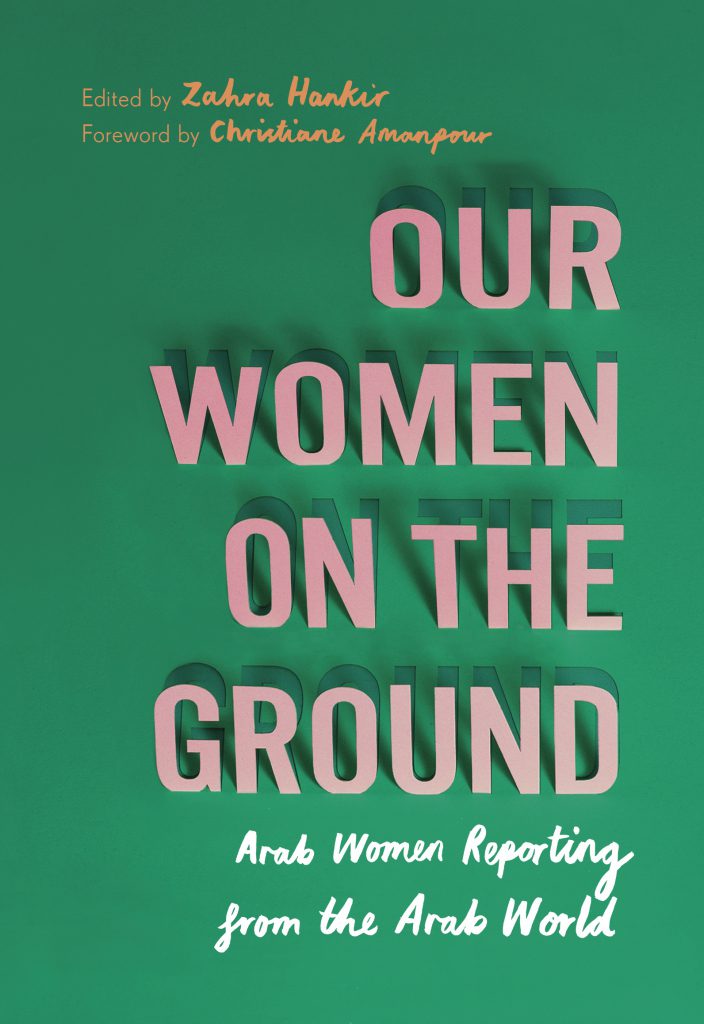

Feeling their voices were underrepresented, Hankir hoped to compile an anthology of stories from those women, which eventually became Our Women On The Ground. The anthology is over 300 pages, including a preface by British-Iranian journalist Christiane Amanpour, most notable for her work with CNN.

“I sought to include a diverse range of women in the book in terms of their backgrounds, countries of origin, religious orientations, political leanings, conflicts they covered and the type of journalism they were doing,” Hankir said, adding that there were so many women she had hoped to include, but only had room for 19. “There are so many incredible women journalists doing this crucial work, but I had to stop at 19 given space restraints.”

Among the 19 are Hwaida Saad and Zeina Erhaim from Syria, Eman Helal from Egypt, Saudi-Yemeni Amira al-Sharif, and Zeina Karam and Natacha Yazbeck from Lebanon.

Our Women On The Ground includes essays from women of different generations, including both women who reported locally and for Western outlets, giving voice to a multitude of truths and experiences. When it comes to the latter, Hankir told Beirut Today she felt they were more “cognizant and aware of the audience they were writing for.”

In addition to their journalistic work, Hankir was particularly awestruck by their humility, especially those from older generations, even questioning the relevance of their own experiences. “Some of the contributors even questioned why anyone would want to read their personal accounts to begin with,” she explained. “The region is filled with tragic stories, so several asked why anyone would want to read theirs.”

Looking at the struggles the Arab women describe in conducting their work, it’s clear that the experiences differ depending on the country they live in. Hankir agrees to that assessment, adding that while some countries fare better than others when it comes to press freedom and women’s rights, “the region generally lags globally on both counts.”

“That said, the local reporters living in more conservative countries have had multiple challenges to contend with specifically pertaining to them being women,” she said, some starting at home where they have to “defy family expectations” and gender roles.

In addition to greater security risks from both states and armed groups for those reporting in war-zones, many women report in countries, such as Egypt, that are notorious for cracking down on journalists even outside of war.

Freedom of movement for many of these women in several cases is a huge problem, for various reasons that are rooted in patriarchy. Hankir relays cases of being unable to move around freely in Yemen without a male guardian, as well as rampant sexual harassment in Egypt. But for many of these women, the bulk of the misogyny and sexism they have had to endure comes straight from the workplace itself.

“Several have faced the challenge of not being taken seriously as a woman journalist in male-dominated newsroom,” Hankir explains.

In addition to shedding light on the struggles these brave female journalists face in their work in the Middle East and North Africa, Hankir also hopes to challenge stereotypes of Arab women –the “orientalist Western gaze”– without diluting the struggles they face on the ground.

“My intention has never been to frame these women in any one way, on the contrary,” she said. “It’s difficult to ignore the power structures in which we operate as Arabs in or outside the West, and how we are perceived in the Western world.”

“There is no one Arab woman, there is no one way to be an Arab woman, and there is no one Arab female experience.”

Hankir added that she hopes to present the nuanced experience of Arab women through the diversity of journalists contributing to Our Women On The Ground.

“If I were to label Arab women anything, it would be resilient.”

The collection of essays by Arab female journalists has received mostly stellar reviews internationally since it was published in August, especially among journalists, Arabs and Middle East politics enthusiasts.

That being said, Hankir believes that while the book directly appeals to a niche audience, its “universal” themes will be a source of connection to even more people. “Resilience, love, loss and identity are universal,” she told Beirut Today. “Many will relate to them, regardless of where they’re from.”

“Guilt is certainly a running theme in the book.”

Looking back at the entire process of curating and editing Our Women On The Ground all this time, does Zahra Hankir have an essay that hits closest to home?

“I’m Lebanese and Arab, but was born in the UK during the Lebanese civil war, so I also had a Western cultural upbringing,” Hankir told Beirut Today. “Both Nour Malas and Hind Hassan reflect on the guilt of having grown up in privilege and at a distance from your home country, while being profoundly connected to it, as opposed to those who were born in or remained in their homelands.”

Female journalists and media workers worldwide continue to struggle for greater representation, in light of patriarchy and misogyny creeping into their daily lives, including their careers. And through some of the essays in Our Women On The Ground, the younger journalists seem to be more vocal when it comes to sharing their personal experiences.

“The women in the book who are of a different generation seemed less preoccupied in their writing with the challenges they have faced over the years, possibly because they have come to terms with them,” Hankir told Beirut Today, adding that they focused more on the profession and the communities they cover. “They seemed less inclined to write about their personal insights.”

“This sort of narrative has not been spotlighted in the way that it should have been in decades past,” she continued. “They’re being given more awards, and more bylines.”

Is it enough? Hankir doesn’t think so. She hopes that this anthology contributes to a positive trajectory that “amplifies their voices and celebrates their incredible accomplishments,” and, most importantly, she says, moves audiences and changes perceptions.

“Readers will cry, laugh, be inspired and moved by these accounts. And their perception of the Arab world and its incredible women may shift as a result.”