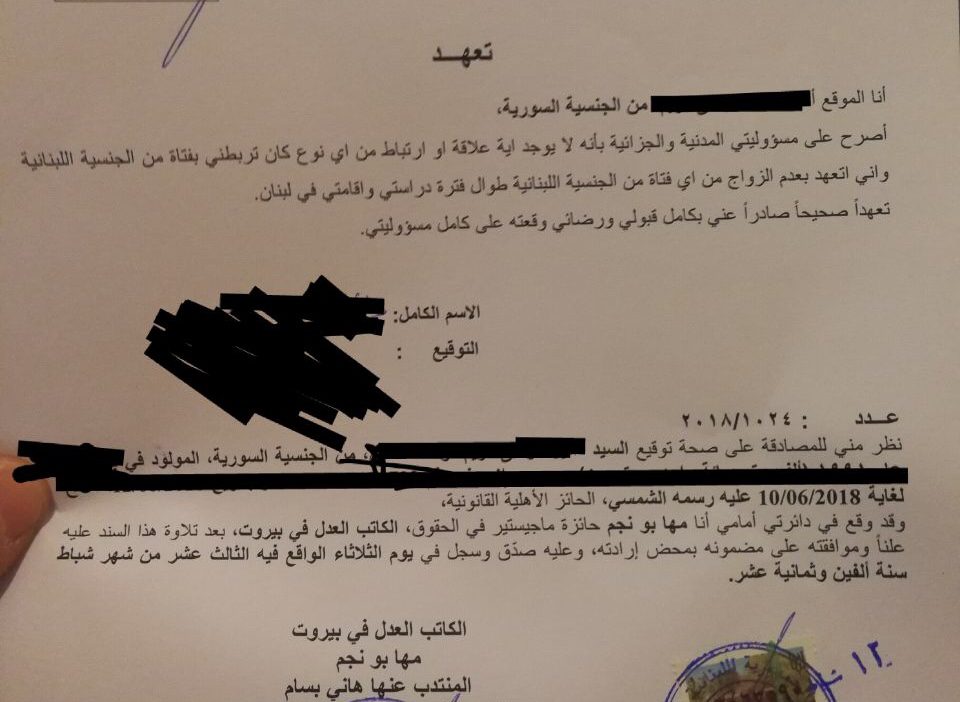

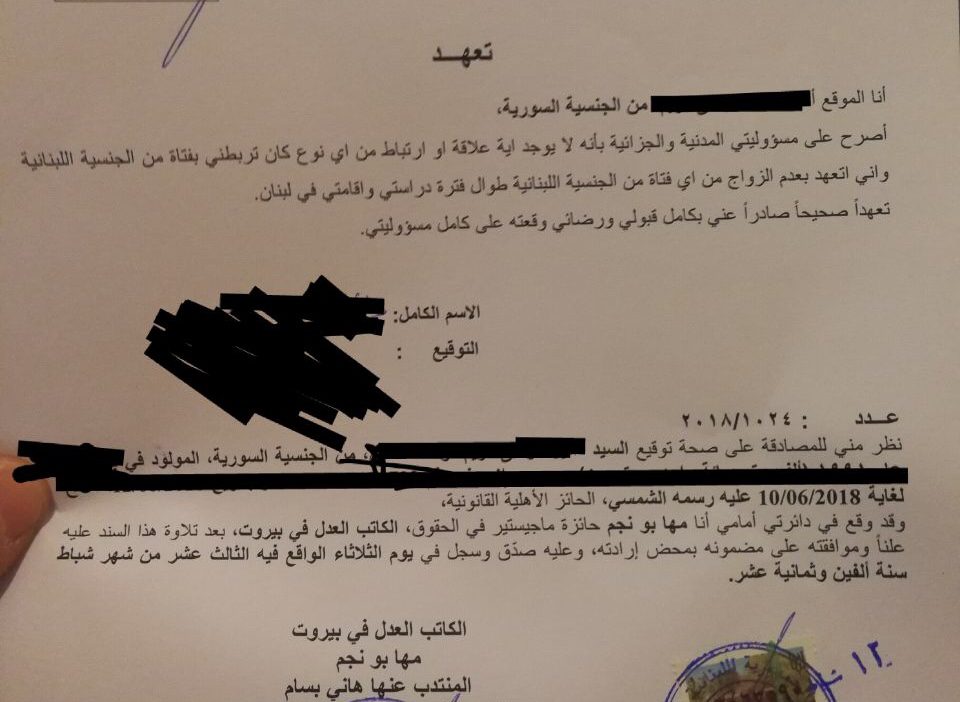

Last week, two events of a similar nature sparked debate and outrage at Lebanon’s “prejudicial immigration” policies. The first of which is a pledge signed by a Syrian student promising “not to marry or associate with a Lebanese woman during his stay in Lebanon” as a requirement for his residency with the General Security.

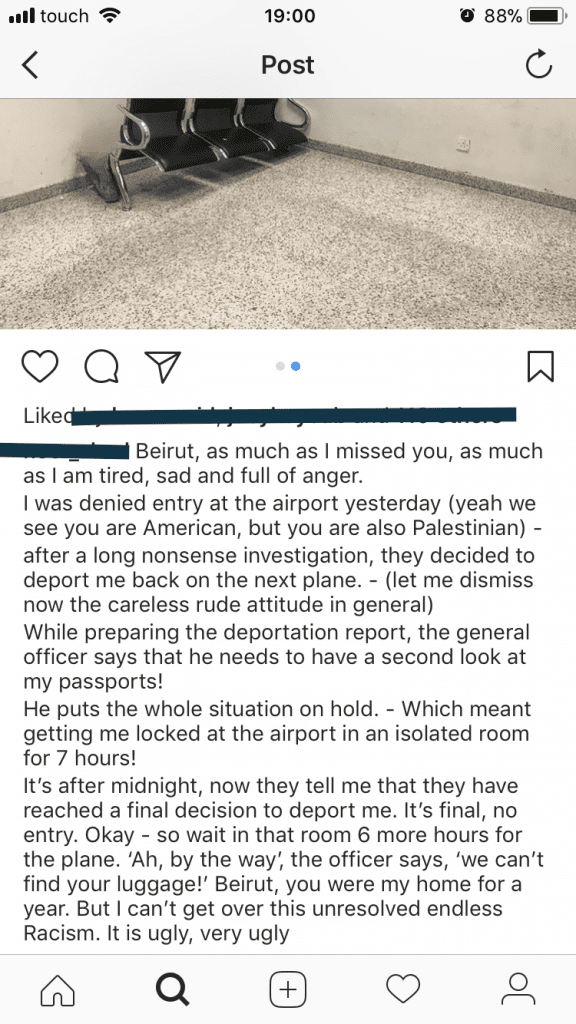

The second of these incidents is that of a Palestinian-American artist’s deportation from Beirut Rafic Hariri International Airport, due to her being “Palestinian”.

These incidents have taken place at a time when xenophobia is seemingly rampant and pervasive in Lebanon, whether it concerns curfews being imposed on refugee communities, residencies becoming increasingly difficult to attain, or even casual conversations with “service” drivers in Beirut.

In the case of the Syrian student, an anonymous source from the General Security made a statement in the Daily Star explaining that the practice is only required of students studying religion. They also stated that this had been in practice since 2003, and is required of religion students in Lebanon from “all nationalities,” rather than being limited to Syrians.

“There are some people who would marry a Lebanese woman so they can receive permanent residence and they can divorce, and they remain permanent residents,” added the source, mentioning that the pledge was created because the type of visa is easier to attain than others and was subject to abuse.

Where is there a human rights violation?

To get a better understanding of these two cases, Beirut Today spoke to Ghida Frangieh, an attorney and researcher at Legal Agenda. Regarding the Syrian student, Frangieh discussed the pledge as violating basic human rights. While his nationality was not the basis for discrimination, the pledge infringes upon both foreign students and Lebanese women’s private lives and their rights to “marry, establish a family and have intimate relations.”

“It violates the student’s rights in two ways,” said Frangieh, “First, the pledge promises that he is currently not involved with a Lebanese woman, and second, he commits that he will not have any relations with a Lebanese woman in the future and renounces his legal right to marry, which therefore violates basic constitutional rights and international conventions.”

This pledge violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 17 Paragraph 1 that states: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.”

The ICCPR was ratified by Lebanon in 1972 and is considered a part of the Lebanese Constitution. After it was entered into force in 1976, the ICCPR legally binds Lebanon through its constitution and international law to uphold its principles.

When asked about the incident about with the Palestinian-American artist, Frangieh answered that she did not have any previous knowledge of this case. She also said: “Her case may be symptomatic of unclear entry regulations and tough entry restrictions for Palestinians,” she said. “Foreigners denied entry to Lebanon are rarely notified in writing of the reasons for this denial, which makes it difficult to identify the problem.”

The Root Cause, And Its Solution

Frangieh stated: “The real problem is that the General Security is the sole authority that elaborates immigration policies, and that regulations are often unpublished, and implemented without any legislative nor judicial oversight.”

“Changes in immigration requirements are often implemented without sufficient notice and publication,” said Frangieh. “Applicants for residency and foreigners seeking entry into Lebanon are faced with ambiguity and a lack of clarity, and advocates face difficulties in accessing immigration-related information and in challenging unjust policies and practices that are not in compliance with constitutional rights and international conventions.”

“There is therefore a real need to review the legal framework in which the immigration authorities operate and ensure legislative and judicial oversight over their regulations and how they are implemented”, said Frangieh

Conclusion

Although the case with the Syrian religion student was not unprecedented, it still did specifically violate Article 17 Paragraph 1 of the ICCPR and thus should be rendered as an illegal practice.

However, since there is no clear legal framework for immigration, some of the General Security’s unsupervised policies and actions are not only illegal but it could be argued that they are illegitimate as well.

Similarly, in the case of the Palestinian-American artist’s detentions for 7 hours may be arbitrary under Article 9 Paragraph 1 of the ICCPR that states: “Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. No one shall be deprived of his [or her] liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedure as are established by law.”

Nevertheless, the little information provided by the General Security on both its immigration policies towards Palestinian and the due process of deportation in Lebanon makes it quite difficult to argue that the artist’s human rights were violated.

Regardless of the context of these seemingly prejudicial immigration policies, some of the General Security’s practices are unlawful and the Lebanese legislative and/or judiciary should take the initiative to monitor the development and enforcement of immigration policies to avoid further human rights injustice.